Fountains have been flowing in Chicago since early in its history, softening the city’s hard edges and soothing its citizens. Alas, scores of these watertossers—from the scandalous Nymph Fountain to the respectable Pioneer Court Fountain—have been destroyed by time, neglect, poor design, changing tastes and tight budgets.

In most cases, all that’s left of these lost fountains is a faded photo, old postcard, or scant written record. But these monuments should not be forgotten. Many of them were beautiful or inspiring. Others were portals to Chicago history. Most have a lot to spout about.

The Nymph Fountain, for instance, was installed one night in early June 1899, under “the friendly darkness of night,” on the lawn south of the Art Institute by students of Lorado Taft, Chicago’s foremost sculptor of the day. The forty-foot-diameter fountain featured eight larger-than-life nude female figures in sensuous poses. The work was a class project, made of temporary materials, but Taft hoped to build it in “imperishable bronze.” Given the reception the work of art received, that would never happen.

University of Illinois Archives

The Nymph Fountain created a stir and attracted crowds that at times required police to manage. It became the “talk of the town,” with politicians, editorialists, and religious figures weighing in. “The nymph is not an intellectual goddess…[and] stands for nothing related to high or noble intellectual accomplishments,” said the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

Such negative reactions left Chicagoans open to ridicule. The New York Times opined, “Preachers, or some of them, think the nymphs should have been provided with mackintoshes [raincoats], while even the most ultra of Chicago’s art cliques would not resent a shirtwaist as a sop to the prudish majority of the city’s population.”

Not everyone in Chicago objected. Mayor Carter Harrison Jr. “trundled down to the lakefront on his bicycle…to take a look at the fountain” for himself and proclaimed it “not in any sense objectionable,” according to the Chicago Tribune. Nevertheless, the prevailing sentiment was shock. Within a few weeks, vandals had “practically ruined” the Nymph Fountain, the Boston Evening Transcript reported. “Nearly every figure in the fountain had been mutilated, and many nymphs had their hands and arms broken off.” The article did not specify whether upright or uptight citizens did the damage.

No, nineteenth and twentieth century Chicago was not like Paris, despite its efforts to elevate itself out of the mud and burnish its reputation built on butchering hogs. In another instance, a fountain created in 1908 by Leonard Crunelle that featured a nude boy was initially welcomed as part of an art show in Humboldt Park organized by the Municipal Art League “to forward the beautification of the city.” The handsome sculpture was “set like a jewel” in Humboldt Park, said the Tribune. “It’s evident at a glance that the scene is improved by the statue, and that the statue is set off by the scenery without the slightest incongruity.”

But after the exhibit, Crunelle’s piece was installed in an alcove on the north wall of the Sherman Park field house near 52nd and Throop streets, where it troubled the Felician Sisters who worked across the street at Saint John of God Church. They objected to the subject’s frontal nudity. The park district removed the sculpture, which has since disappeared. The alcove and basin are still there, the latter used as a planter.

Similarly, in 1887 the commissioners of Lincoln Park ordered that the private parts of Storks at Play’s merboys be covered with fig leaves. (The coverings were later removed.) And the original design of the 1893 Rosenberg Fountain in Grant Park portrayed the Greek goddess Hebe topless. Hebe is a cupbearer to the gods, and myth holds that Apollo dismissed her after she indecently exposed her breasts while serving drinks. The fountain’s sculptor originally portrayed Hebe topless, but the executors of benefactor Rosenberg’s will selected a safer design out of deference to public taste. The fountain, which still stands at Michigan Avenue and 11th Street, depicts Hebe wearing a clinging diaphanous gown and exposing only one breast—a design the Tribune dubbed “Hebe the Second.”

Chicago History Museum

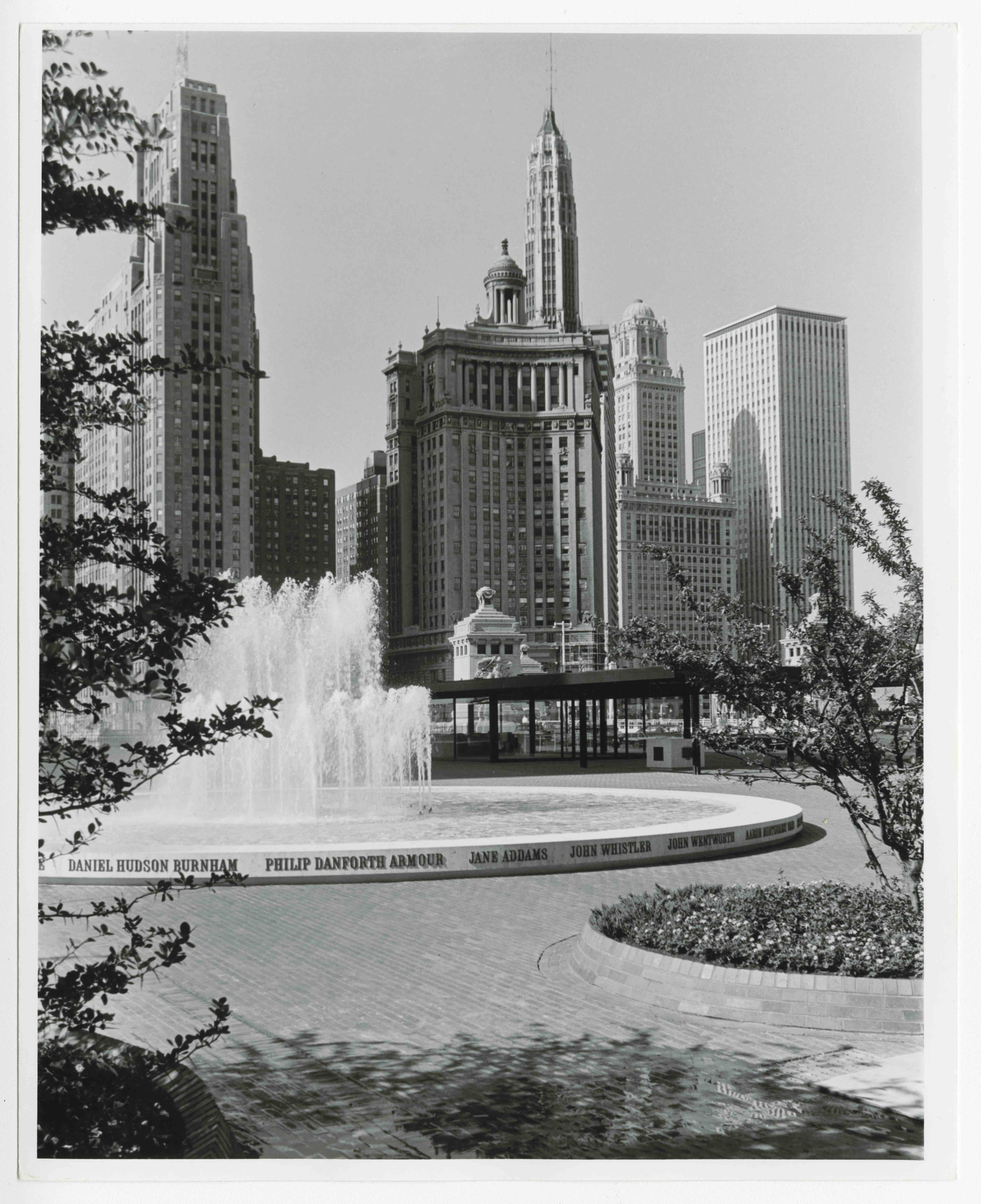

The handsome fountain stood in the plaza that’s now being turned over to the new Apple Store. Its 50-foot-diameter marble basin echoed the openness of the 80,000-square-foot plaza. At the same time, its several jets shot water high into the air, mirroring the tall nearby buildings.

The plaza dates back to the early 1960s, when Equitable Life Assurance replaced a parking lot there with its building at 330 N. Michigan Ave. The fountain debuted in 1965, and the rim of its basin became a popular spot to sit, lunch, and people watch.

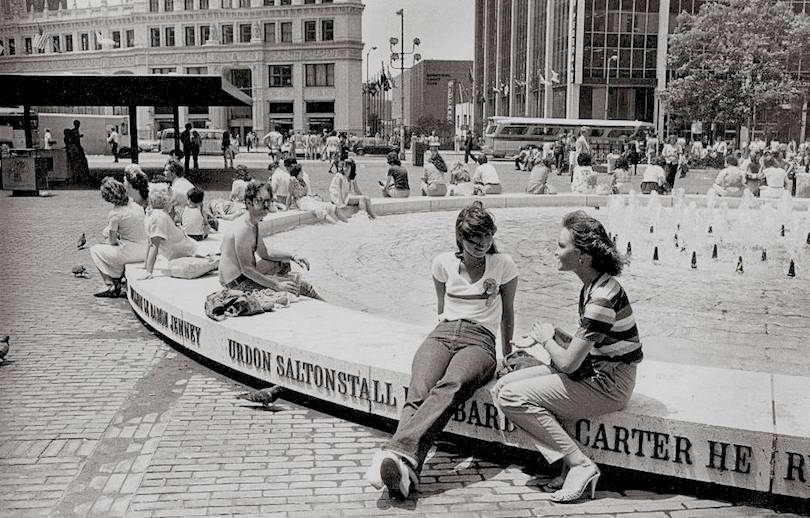

Chuckman Collection, 1981

The fountain was installed in 1965 and lasted only 25 years, ironically matching the number pioneers it named. It’s not known what became of the letters that spelled out the pioneers’ names, a few of which were missing when the water still flowed. The New Pioneer Court Fountain, stretching 300 feet, is attractive but less striking or impressive than its predecessor.

The society also installed smaller drinking fountains. It’s most common design was a modest affair featuring a faucet facing the sidewalk for people, a trough extending into the street for horses, and a basin for dogs flaring out from the base, which was inscribed “Illinois Humane Society.” By 1877 the society had sprinkled nine such fountains around Chicago and sixty by 1913, making it the most common fountain in Chicago.

Incredibly, two Illinois Humane Society Fountains remain and still function. One is at the northeast corner of Michigan and Chicago avenues; the other is nearby, just a few steps west of the Water Tower. Carriage horses that queue up there at Jane Byrne Park drink from the latter. These iron fountains are more than one hundred years old, yet tens of thousands of people pass by them daily without any idea of their historical significance. If they knew, they might stop to admire the fountains’ attractive Victorian style and quaint, diminutive size. They might also take a selfie—and, more importantly, a sip.

Photo by Julia Thiel; copyright Greg Borzo

Most of these fountains were stolen. In the early 1960s, Charles Gasperik “liberated” one of them in the middle of the night. “At one time, there were scores of these fountains all over town, but many were torn out for scrap, especially during World War I,” he explained. “One near Clark and Lunt (streets) was put at risk when the store it stood in front of closed and there was no one left to protect it. So, friends and I rescued it one night. In case the police came by, we had a story cooked up about taking it to the Art Institute.”

Gasperik kept the relic in his garage until 1985, when he donated it to the Sulzer Regional Chicago Public Library. The library considered installing it in the triangular lawn south of its building but never got around to it, according to a library official. Years later, the city placed the fountain in storage and it’s never been heard from since. This fountain should be refurbished and installed, either at Sulzer or the fountain’s original location.

Initially people drank from these and other fountains using a metal cup chained to the base. At that time, it wasn’t known that cup sharing made people sick, but that changed gradually. In 1909 a Tribune article under the headline “Danger in the Cup” said, “It’s everywhere conceded the common drinking cup is a prolific means for the transmission of diseases.” Soon “Ban the Cup” campaigns spread across the country, and in 1911 Illinois prohibited what had become known as the “death cup.”

Chicago History Museum

Chicago Park District, Special Collections

The 1890 Yerkes Electric Fountain in Lincoln Park was ahead of its time, combining water and electric lights, and foreshadowing both the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 and Buckingham Fountain. The spectacular waterworks attracted tens of thousands to Lincoln Park. The dazzling seven-foot-tall piece was 120 feet in diameter. It had two rings of jets shooting water inward and one central jet shooting water as high as 110 feet, creating a pyramid effect. The ruthless Charles Tyson Yerkes, an archetypical nineteenth century robber baron who built much of the Chicago ”L,” funded the fountain in an attempt to burnish his poor reputation with the public, press and politicians.

Everyone gushed over the popular attraction. An 1895 history of Chicago said, “The projection of strong electric light through colored glass on falling water…renders Lincoln Park one of the most favored pleasure grounds in the country.” A reporter compared Yerkes to Caesar, who created “public spectacles of such magnificence that he became at once the people’s idol.” The Electric Fountain didn’t make Yerkes an idol or even do much to improve the negative views of him. People realized the best way to get to the fountain was to ride Yerkes’ cable car line to Lincoln Park, prompting the Tribune to note, “Thousands dropped nickels into the importunate hands of Yerkes’ conductors for the sake of looking at Yerkes’ ‘gift.’”

Yerkes was more or less run out of town in 1899 by disgruntled colleagues, dissatisfied transit riders, and a hostile press. This left no one to advocate for his Electric Fountain or pay for its expensive upkeep. Neglected and vandalized, it was removed in 1908.

Many fountains decorated Chicago’s two world fairs. The Columbian Fountain was a focal point of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Dominating the central Court of Honor, this magnificent piece featured Columbia atop the Barge of State, heralded by Fame, oared by the Arts and Industries, and guided by Time at the helm—all of which was surrounded by numerous water jets. Later, the 1933-34 Century of Progress featured many waterworks, but the Exposition Fountain in the North Lagoon stole the show. With a flow of 68,000 gallons a minute, it was billed as the largest fountain ever built. It included a 570-foot-long series of ostrich plume jets culminating in a dome of water more than 75 feet wide and 40 feet high.

American Architect, 1934

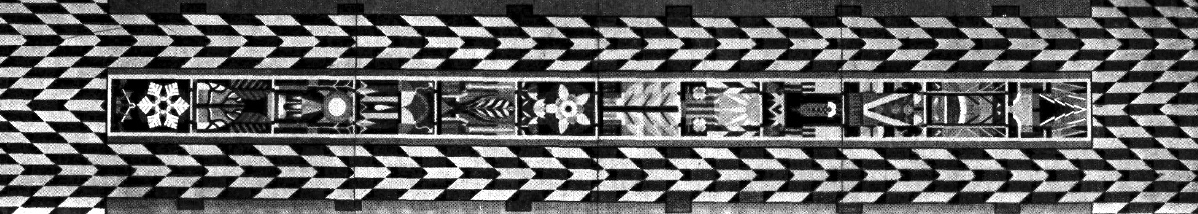

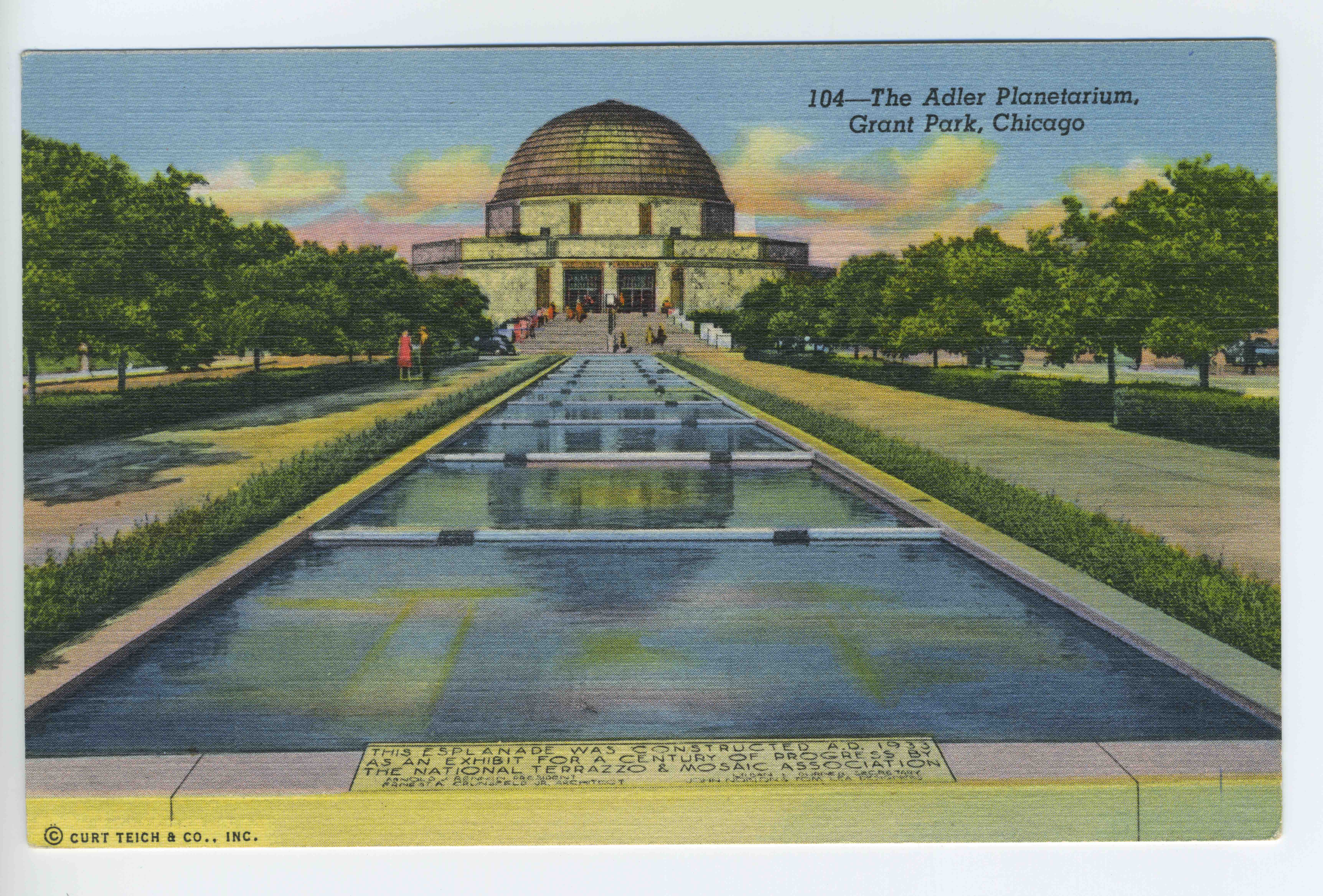

The Century of Progress’ Cascade of the Months was built as a permanent installation and survived for several decades after the fair. Located in front of the Adler Planetarium, it was the focus of a 500-foot-long, 93-foot-wide esplanade that the National Terrazzo and Mosaic Association built as its exhibit for the fair.

Curt Teich Postcard Archives

One of Chicago’s most distinctive lost fountains, this masterpiece featured twelve colorful ground-level terrazzo panels, one for each month. A thin sheet of water flowed over them and accentuated the shimmering effect of the bright, underlying terrazzo, which is composed of ground marble, glass, stone, or metal mixed with a binder, such as cement or epoxy. The mixture is then poured into patterns outlined by metal strips, allowed to harden, and polished. With the Cascade of the Months, craftsmen used more than 50 colors of paint and marble chips in a binder of white portland cement. The work sparkled, at least initially.

After the fair, the fountain fell into disrepair. By 1968 the work was in a deplorable condition. The planetarium removed it circa 1970 during a building expansion project. Although Chicago’s freeze/thaw cycle can be merciless, Richard Bruns, executive director of the association, said, “The planetarium’s installation could have been maintained because we have exterior installations from the early 1900s that are still in good shape.” Those who remember the bright terrazzo panels covered with flowing water must miss this “glistening magic carpet of color harmony.”

Riverview Park boasted Creation, a dazzling display of water with a highly decorated wall symbolizing creation as a backdrop.

Architectural Forum, 1930

In a few cases, physical remnants of lost fountains poke out, hidden in plain sight. The defunct Victor Lawson Memorial Fountain on the east side of the former Chicago Daily News Building along the Chicago River at 400 W. Madison Street is an empty shell. (Lawson was the longtime owner and editor of the newspaper.) This once mighty fountain had an unusual design: three large portals about 25 feet high gushed water into a semicircular basin near ground level. It has not run for decades and unlikely to ever operate again.

Art Institute of Chicago

When they were built in 1929, the Daily News Building, plaza, and fountain made big news. “Their beauty will be massive, symmetrical, thoroughly American, and modern,” raved the New York Times. Especially important was the way the edifice embraced the river, decades before such a practice was required. In fact, the building was Chicago’s first significant modern commercial skyscraper to face the river, opening its arms to the river with its 400-foot-wide plaza, highlighted by its commanding fountain.

The Gateway Park Fountain, a beloved water spectacle in front of Navy Pier, lasted only twenty years. When it opened in 1995, Chicago celebrated its fun interactive design. “Watch out Buckingham Fountain,” shouted a Tribune article that went on to quote a tourist saying, “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

The computer-programmed water wonder featured a large black granite block with more than twenty “skyrockets” that shot water as high as 100 feet. Surrounding the block, 200 “nanoshooters” buried at ground level delivered unpredictable bursts of water one-inch to six-feet high in fast-acting sequences. Kids chased around the dancing spurts of water and clung to the five-foot-high granite block to catch water cascading over its sides.

The fountain “explodes, with a dozen plumes of water high into the sky,” wrote the Tribune’s Rick Kogan. “Water shoots from holes in the pavement. Children giggle and get wet. Mothers and fathers sit there, watching in wonder the power and beauty of the liquid fireworks.”

Nevertheless, in 2016 the Gateway Park Fountain was demolished. The good news is that it was immediately replaced with a similar waterworks. The Polk Bros Foundation donated $20 million to remake the 13-acre Gateway Park—and rename it Polk Bros Park. The work included the new 75-foot-diameter Polk Bros Park Fountain. This interactive waterworks is equipped with more than 250 programmable water jets. The illuminated, multicolored piece “mimics the natural movements of waves, schools of fish or flocks of birds,” according to its designer. In the winter the area can be transformed into an ice-skating rink.

Finally, parts of fountains that disappear can be repurposed in a different time and place. Such was the case with Charitas. The eight-foot-tall bronze statue of Charitas debuted in 1922 as part of a fountain featuring a wide basin and water jets. It stood atop a large, square pedestal at one end of the basin. Ida McClelland Stout won a Daily News competition to sculpt the statue, which depicts a woman holding two children and symbolizes charity to underprivileged youth. Its original placement in Lincoln Park west of the Daily News Fresh Air Sanitarium—a health center that accommodated more than 30,000 children a summer during its peak—recognized the humanitarian work done there. (“Charitas” comes from Greek for charity.)

Chicago History Museum

When work on the northbound lanes of Lake Shore Drive in the late 1930s required removal of the fountain and a portion of the sanitarium (now the Theater on the Lake), the park district moved the statue to the Garfield Park Conservatory. Regrettably, the conservatory painted the bronze statue white to match Pastoral and Idyl, two white marble figures sculpted by Lorado Taft on display there. In the 1990s expert conservationist Andrzej Dajnowski removed the paint from and restored Charitas, but in 2001 the conservatory moved the statue into storage to make room for its blockbuster Dale Chihuly exhibit, “A Garden of Glass.” The statue remained in storage, even after Chihuly’s exhibit closed the following year. “No charity for Charitas,” said the Sun-Times in 2003.

In 2016 the park district reinstated this lovely statue south of the Theater on the Lake, near where it originally stood. Although no water bubbles around Charitas, Stout’s statue has been returned to its original pedestal, which during the intervening years held the bust of George Solti in front of the Lincoln Park Conservatory.