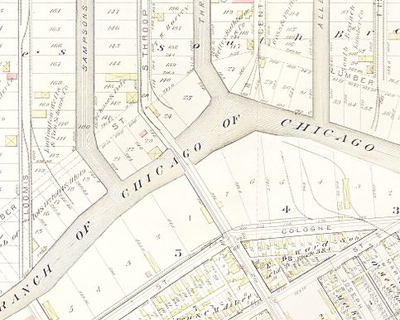

In Chicago, a disused or demolished crossing of every type can be found. Here we are focusing on vehicular bridges over water where a connection no longer remains. There are three waterways in Chicago proper which are crossed by vehicular bridges. The Calumet River, Chicago River, and the Sanitary and Ship Canal. There are also waterways which no longer exist, most notably the West Fork of the Chicago River which was replaced by the Sanitary and Ship Canal. Unfortunately, there are no known remnants of the West Fork.

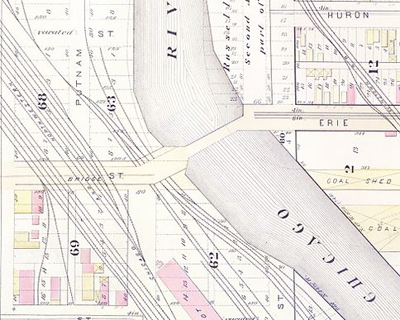

Robinson’s Atlas of the City of Chicago, 1886, Chicago Historical Society. |

The Calumet River and the Sanitary and Ship Canal do not have any ‘lost’ vehicular bridge crossings. In other parts of the Chicagoland region, there are more lost bridges to be found. Two notable examples include the Old Western Avenue bridge over the Cal-Sag Channel in Blue Island, and the Lawndale/Lincoln Avenue, former IL-171 bridges over the Des Plaines River and Sanitary and Ship Canal in McCook and Summit.

There are seven ‘lost’ crossings on the Chicago River’s current configuration. Two of these were part of the Ogden Avenue Viaduct which was removed in 1992, and is discussed at greater length here.

Of the remaining five, Fuller Street (at left) has the least discernible remnants. One of the namesake bridges of Bridgeport, it appears to have been removed in the 1910s. The passage of 90+ construction seasons accounts for the relative lack of remnants. There are some small ones though – if you go to the edge of the park which now occupies the west bank of the river on the former site of the bridge, you can still see some wooden pilings. The park features an excellent diagram of changes in the area over the past 150 years.

Prior to 1972, there had been a crossing at Polk street for at least 120 years. The first bridge constructed at this location was so old, it predated city records. Characterized as nothing more than a “floating tub,” it was replaced in 1869 by a swing bridge. This bridge was obliterated by the 1871 Chicago Fire and was replaced with another in 1872. The latter swing bridge served for 35 years before it was replaced. The last bridge on this site was installed in 1910 and was no ordinary Chicago-style trunnion bascule bridge. It was designed by Joseph Strauss, who would later become famous as the chief engineer of the Golden Gate Bridge.

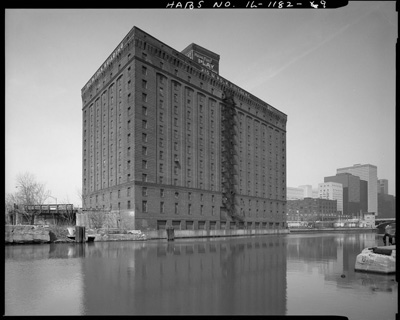

Left: DN-0056536, Chicago Daily News negatives collection, Chicago Historical Society. Right: HABS ILL,16-CHIG,167-9.

Right: A similar view in 1991, with the viaduct and bridge footings, but not the bridge, in place. The large building in this image is the Marshall Field River Warehouse. Designed by Daniel Burnham, it was completed in 1904. It would change owners a number of times before it was acquired by the Postal Service in 1974. It would be torn down twenty years later, replaced by a modern postal facility.

Left: HABS ILL,16-CHIG,167-8. Right: HABS ILL,16-CHIG,167-16

Two 1991 views of the west bridge footing and the Marshall Field River Warehouse. In the image at left, the decorative concrete railing of the viaduct can be seen between two cars. It is similar to the nearby Canal street viaduct. This viaduct was demolished and replaced along with the new postal facility on this site.

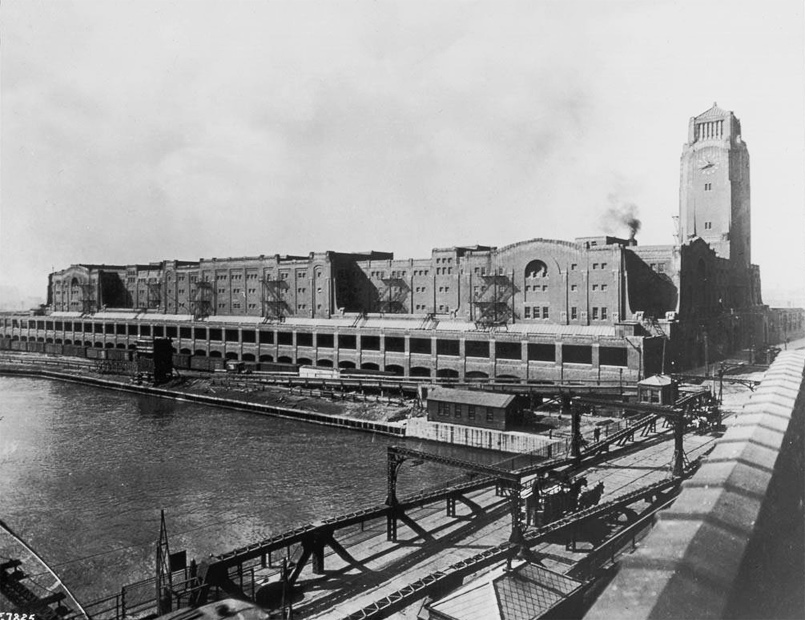

Ryerson-Burnham Digital Archives, SAIC.

Strauss’ bascule design was fairly plain compared to more ornamented contemporaries. By the 1960s, the usual Chicago program of deferred maintenance allowed it to deteriorate significantly. The narrow roadway also rendered it obsolete as the narrow 21 foot wide right of way discouraged any heavy traffic. Newer and more adequate spans at Roosevelt and Harrison could easily handle the traffic of the vacated bridge. It was slated for removal in 1971, but objections from local businesses earned it another year. During this time plans were made to replace the bridge, but these proved cost-prohibitive.

The city’s bridge engineer in 1972, Louis Koncza, predicted that the bridge would eventually need to be replaced in order to accommodate traffic from planned residential development in the South Loop on former railroad property. Some of this property has since been developed, however Polk street east from Canal to the River is now a private road used by the Postal Service. The postal facility that replaced the Marshall Field River Warehouse can be seen at right along with the remnants of the bridge footings.

River City, the earliest South Loop residential development, lies directly in front of the the eastern right of way (it is out of view to the right side of the left image). It is highly unlikely that residents would support a bridge approach in their front yard. Mr. Koncza’s prediction is not going see fruition, and the Polk Street bridge will remain a vague memory.

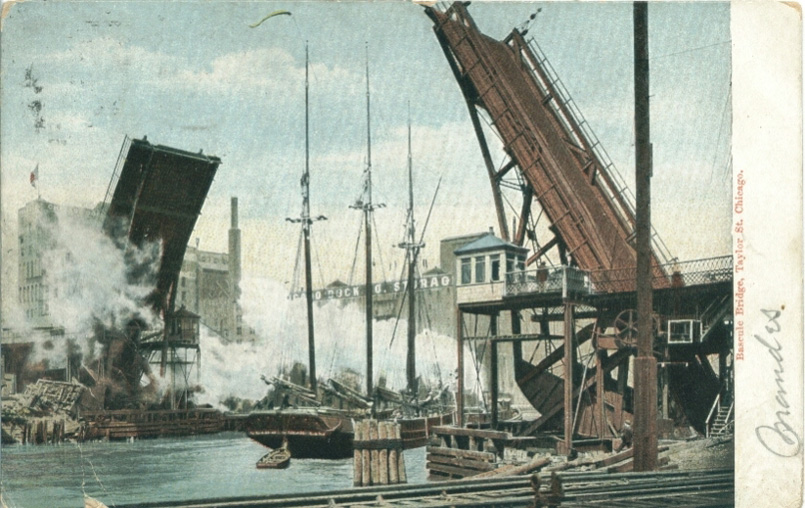

The Taylor Street bridge existed longer as a concept than as a physical reality. Citizens of the Near West Side pushed the issue of bridging Taylor street starting in the 1850s, and the Board of Public Works had plans prepared as early as 1874. However, there were no results from any of these early efforts.

By the mid 1880s, still without a bridge, residents and business owners in along Taylor immediately west of the river further pressured civic leaders. These residents and businessmen argued that the 12th and 18th Street bridges were inadequate to handle increased traffic to their growing business district. Some aldermen argued against building the bridge, claiming that Taylor Street was not in good condition for traffic and did not have a street railroad, while other aldermen suggested that residents of the area pay directly for the bridge. This was an era where the city was not necessarily responsible for such capital improvements, and bridges were more often built by street railway companies for whom crossing the river was a financial imperative.

View west along the former path of Taylor Street from the east bank of the river. Some evidence of the Taylor Street bridge remains, most notably the footings on the west bank.

|

By 1886, two competing street railway interests were vying to build a bridge at Taylor Street. The City Council preferred granting permission to railroad tycoon Charles Tyson Yerkes, however, an upstart rival company called the Union Passenger Street Car Company was also looking for a right-of-way over the river at Taylor Street. Eventually, Yerkes’ company was chosen, however, an error made by the City’s Law Department allowed Yerkes to delay payment for the bridge, effectively transferring the cost to the City.

In 1890, the superintendent of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy railroad sent a letter to Mayor Cregier stating that the company would claim damages if a viaduct approach on Taylor was built over their tracks. This letter was dismissed by the press and the public, considering that the presence of the railroad created an unsafe grade crossing. It turned out to be an empty threat by the railroad company as the viaduct approaches were completed in 1892. These approaches sat unused until 1900, when the bridge itself was finally built. By this time, the approaches had fallen into a state of disrepair. The plank sidewalk rotted through, the road had become pitted, and the iron railings rusted over. Presumably, these were repaired concurrently with the opening of the bridge.

The bridge was notable as it was the first Scherzer rolling lift bascule installed in Chicago. This type of bridge differs from the trunnion bascule in that the counterweight and rolling mechanism are prominent on the exterior rather than concealed in the support structure. While only one bridge of this type remains in Chicago, the Cermak Road bridge, there are four spanning the Des Plaines River in Joliet.

Chicago Historical Society

The Taylor Street bridge was eventually removed as part of the straightening of the Chicago River between Polk and 18th Streets. The straightening project, part of the famous Burnham plan, began in 1926 and was finished by 1930. In a 1926 Tribune article detailing the tasks to be completed as part of the project, the twenty-six year-old Taylor Street bridge was described as “old.”

The two images above show the straightening project in 1929. The image at right is an enlarged crop showing the Harrison, Polk, and 12th Street bridges. Just north of the 12th Street bridge (the image is looking north), there is a bridge disconnected from a crossing, which is very likely the Taylor Street bridge in transit.

Photographer unknown

In Bridgeport, there have been six vehicular crossings of the main branch of the Chicago River, including the northern section of the South Fork. Three are major and have existed for quite a long time; Archer, Ashland and Halsted. The other three are minor, and for some reason, difficult to find information about. These are Fuller, Loomis, and Throop. Fuller, discussed earlier on this page, predates Loomis and Throop. However, we have not been able to place the exact date it was removed. In the spirit of ‘good enough’, we can verify that a connection existed at Throop at least since 1886 and at Loomis not earlier than 1895.

The property formerly occupied by the Throop Street bridge on the south bank of the river is now occupied by a construction company and is private property. As such, we only have views of remnants from the north side of the river. The image at left shows what is left of the southern footing, while the image at left shows the current terminus of the northern viaduct approach. This approach to the bridge is largely intact, although it is blocked off. Another barrier at the end of the approach further protects un-savvy drivers from plummeting twenty feet into the river. Also, streetcar rails can be clearly seen in the pavement. These same rails jut out past the blockade where the road is literally cut off.

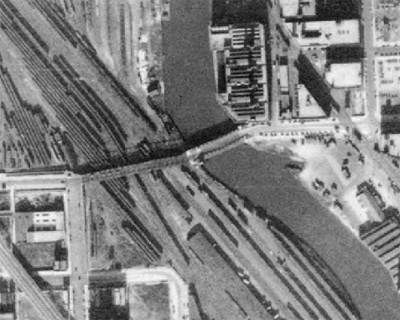

Left: Robinson’s Atlas of the City of Chicago, 1886, Chicago Historical Society. Right: 1938-1941 Illinois Historical Aerial Photographs, Illinois State Geological Survey.

Prior to being renamed Throop in a pre-Brennan continuity improvement, it was called Main Street in old Bridgeport’s angled section. The bridge carried streetcars into Bridgeport beginning in 1895. An incarnation of the 44 Wallace-Racine route ran on the bridge, as streetcars until 1951, and buses until 1977, when the bridge was removed. Bridgeport resident John Magala describes the bridge in the years prior to removal as underused, rickety, and outmoded. It was closed in 1977 in concurrence with the opening of a new, award-winning bascule bridge at Loomis.

Left: Robinson’s Atlas of the City of Chicago, 1886, Chicago Historical Society. Right: 1938-1941 Illinois Historical Aerial Photographs, Illinois State Geological Survey.

DN-0008116, Chicago Daily News negatives collection, Chicago Historical Society. |

The story of the Erie Street bridge is nearly identical to that of the Polk Street bridge save for the Joseph Strauss part. It was a regular trunnion bascule bridge, the type most commonly associated with Chicago. Like the Polk Street bridge it was built in 1910, but was removed one year earlier in 1971. The reasons for removal were the same; a lack of maintenance and obsolescence due to a narrow roadway preventing heavy traffic. The roadway of the bridge was 38 feet wide, however, the width of the roadway on the viaduct approach was a pitiable 19 feet. In addition, the Erie Street bridge was one block north of the massive Ohio Street bridge, built in 1956 as part of the Ohio Feeder Interchange connecting the Kennedy Expressway to River North. The Erie Street bridge would have seemed even more outmoded by contrast.

Right: The viaduct was demolished along with the bridge in 1971, but the approach, seen here, is still intact. Interestingly, there is a very small bit of plank sidewalk at the end of the approach, on the north side of the street in the small swath of trees seen in this image.

Roy Hall, Chicago Tribune

- Bridgeport’s Chicago & Alton Railroad Bridge

- South Western Avenue Improvement

- The 12th Street Bridge That Never Was

- Lake Shore Drive Redux

- The Little House on Polk Street