Ogden Avenue is an arterial highway in Chicago, running southwest from the near west side. The street was closed to traffic between North Avenue to Armitage Avenue in 1967. Another block was closed in 1983, south from North Avenue to Blackhawk Street. Finally by 1993, the viaduct carrying it over Goose Island was demolished, effectively cutting the route back to Chicago Avenue. The street did not need to be closed, but was done so as a result of poor planning and deferred maintenance.

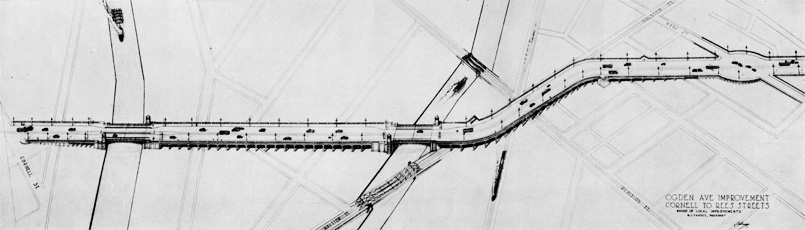

Ogden Avenue was originally called Southwest Plank Road. Built in 1848, it was ten miles long and ended in Riverside. The name was changed in 1877-78 following the death of Chicago’s first mayor, William B. Ogden. Plans to extend Ogden beyond Union Park, and improve the rest of the thoroughfare, were floated around at least forty years before it finally happened in 1922. As early as 1880, the issue of extension from Union Park to Lincoln Park was a platform for aldermanic campaigns. However, improvements were not seriously considered until 1900. It was not until the Plan of Chicago, authored in 1909, which advocated such improvements, did the project gain momentum. It was approved by the Chicago Plan Commission in 1916, and the City Council in 1919.

The initial route planned for the extension was slightly different than the one eventually adopted. Originally, it ran just south of the later route, terminating instead at the intersection of Lincoln Avenue and Wells Street. The city council voted against the improvement in 1902 because they found it to be too costly. At some point, a cost-saving zigzagging route was proposed, which would have involved condemning less property, but was eventually dropped in favor of the original plan. The final terminus was the intersection of Armitage and Clark, about three blocks north of Lincoln and Wells.

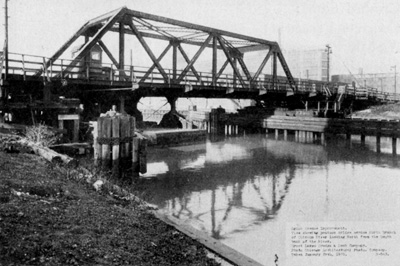

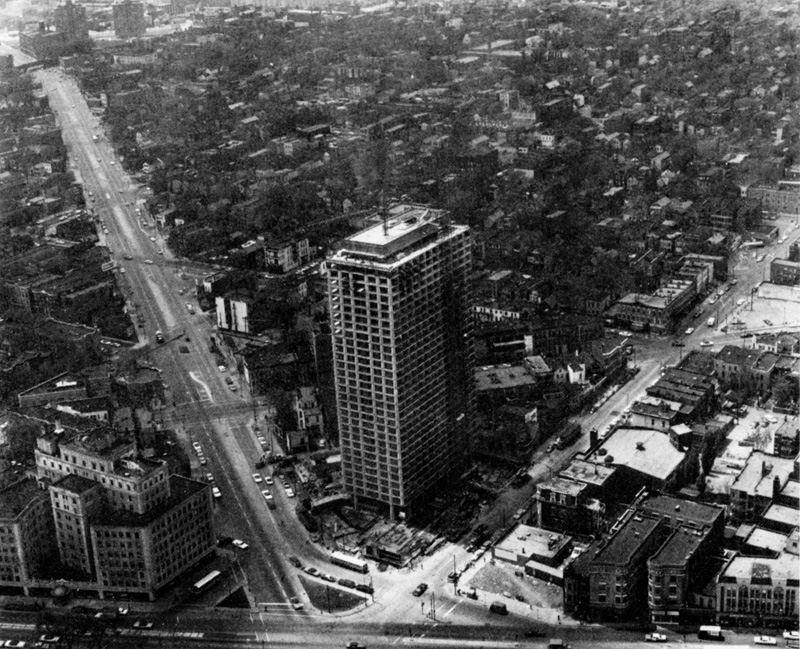

Chicago Architectural Photo Company, January 1931.

Chicago Architectural Photo Company, January 1931.

There were many reasons in favor of extending the road, and few against it, beside the early cost concerns. The cost of the initial improvement was approximately $5 million. The viaduct over Goose Island, which was begun in 1932, cost another $8 million. There was good reason for the city to invest this much money to improve Ogden. The land along the proposed route, especially Goose Island, was euphemized by Charles Wacker as “stagnant,” but conditions were likely appalling. Goose Island had always been an underdeveloped area criss-crossed by grade level rail lines. Consisting primarily of industrial land, there were workers’ cottages on it as well, but economic conditions in the area were poor. Goose Island also had a reputation for its foul smell and repulsiveness. One writer referred to it as “the home of all abominations.” In the early period of the Ogden extension plan, there was talk of converting Goose Island into a park. This never came to fruition as city planners had a better idea for the island. It was thought that extending Ogden through Goose Island would stimulate industrial development in the area, which it eventually did. Also, it should be noted that the only access point from Goose Island to Ogden was a ramp at Hickory street.

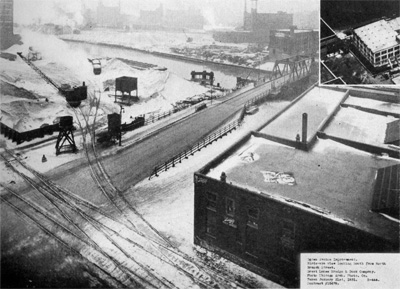

Left: Chicago Aerial Survey Company Right: Chicago Architectural Photo Company

Left: Chicago Aerial Survey Company Right: Chicago Architectural Photo Company

There were financial benefits to be had from the extension. Such a large civic improvement was almost sure to increase property values in the area, and in turn provide the city with increased tax revenue and more power to attain larger bonds in the future. It is uncertain that the city ever saw such a great financial return from extending Ogden, as some important planning issues were overlooked and the street never developed to its full potential.

| The facilitation of retail development along the street should have been a top priority for the city after the street had been extended. An important reason for extension and improvement was that a new, large commercial artery was going to be created. Commercial development did occur to some extent, especially south of Chicago Avenue. Most of the businesses that developed on Ogden were auto-related services. Similar development occurred on other major diagonal streets, such as the motels on north Lincoln and south Archer, as well as establishments like hot dog stands, service stations, drive-thru’s, etc. What differentiated Ogden from streets like Lincoln was the absence of other types of commercial development. For example, a supermarket was never built on the Ogden extension. Restaurants and shops were few and far between. An issue that could have been easily avoided with more careful planning, is that the extension disrupted the grid pattern. Other diagonals, including the original section of Ogden, were Indian trails before they were streets. The street grid grew naturally around them, where the Ogden extension slashed through it. This created a number of problems. In terms of retail development, the slashing through the grid caused oddly shaped plots and residences backing on to Ogden at angles. An modern day example is the Matchbox Bar, located at Chicago and Ogden. The building is a tiny sliver, barely enough to hold one of the smallest bars in the city. The available property was stunted, suited only to small, inconsequential development in addition to being aesthetically unattractive. |  Ron Schramm Ron Schramm

Rendered in a machine-age graphic style similar to that of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, this plaque and others like it adorned the Ogden viaduct’s bridge houses.

|

2004 CTA Historical Calendar.

2004 CTA Historical Calendar.

There were more reasons to extend Ogden. It was hoped that by giving west side residents better access to Lake Michigan, it would improve their quality of life. Others included easing traffic in the central city, much like Interstate 294 does for the metro area today, improving connectivity, and providing a direct route from the lake to points west. It was not only the extension that was improved. In fact, the entire street was improved and transformed into a modern highway connecting the city to suburbs such as Riverside, Naperville, Plainfield, and Joliet. A few years after Ogden’s initial improvement, it was incorporated into the nascent U.S. highway system. Ogden, from Harlem Avenue, to the intersection of Jackson and Paulina streets, carried U.S. route 66, one of the most famous pre-interstate highways, through Chicago. U.S. route 34, which paralleled 66 to some degree, was also assigned to Ogden. Both of these have since been decommissioned through Chicago, and few U.S. highway routes traverse the City today. This is due to the rise of the interstate freeways, which would prove to be a factor in Ogden’s demise.

Following the great depression, the housing stock in Lincoln Park, like many neighborhoods, began to slip into decline. Some reasons for this decline included the conversion of larger buildings to rooming houses, which in turn caused overcrowding. Deferred maintenance, and the use of inferior building materials were some other problems. The first community organization, of seven that would eventually form in the area, was the Old Town Triangle Association (OTTA), organized in 1948. Its formation marks the official beginning of urban renewal in Lincoln Park.

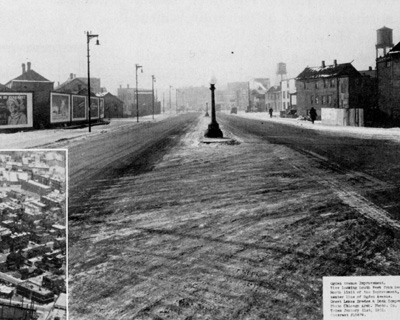

Photographer unknown

Photographer unknown

The purpose of these organizations was to combat something called “blight”, a catch-all for everything residents found undesirable. It is a vague term for general deterioration, thrown around in the urban renewal literature of the day. “Urban renewal” itself is a phrase that is ambiguous, and has gained a negative, almost ironic connotation over time. Its meaning differs from city to city and neighborhood to neighborhood. Urban renewal in Lincoln Park consisted of selecting outmoded or code-violating buildings for demolition, eliminating mixed uses, creating more open space, and closing off and/or eliminating streets.

The Lincoln Park Conservation Association (LPCA) was formed in 1954 in order to oversee organizations like OTTA and others that followed. Their main goal was to improve the quality of residential structures and livability in Lincoln Park. In the Lincoln Park General Neighborhood Renewal Plan (GNRP), the LPCA goes into detail regarding elements that needed to be added or eliminated. The first part of the plan, Project One, calls for the removal of Ogden Avenue north of North Avenue. It was a flawed plan.

The ultimate goal in improving and emphasizing residential structures was the retention of residents. In many other areas of the city residents were moving out to suburbs, in turn causing further physical and psychological deterioration of neighborhoods. All measures taken by the LPCA were done in order to avoid the same thing happening in Lincoln Park. Key policies of the GNRP included the separation of vehicular and pedestrian traffic, and separation of residential, commercial, and industrial zones. One correspondence advocated the elimination of “harmful mixed uses.” Other policies included the removal of outmoded structures, building more open space and parks, and widening preferred (major) streets.

Left: Cooley High. Right: Ron Schramm

William Friedlander, then executive director of the LPCA, was quoted as stating: “Ogden Avenue is a wide street carrying very light traffic. It cuts up the area and is a waste of land”. There is no simpler way to explain the party line and popular sentiment at the time regarding Ogden Avenue. With a 108 foot wide right of way, Ogden was by far the widest street in the area, the one most suited to carrying heavy traffic. It had very little traffic, for which the GNRP offers five reasons.

In Project One, it is argued that traffic volume on Ogden was far below designed capacity, and that only a small percentage of traffic in Lincoln Park was oriented towards distant points west. Because of this, the street could be vacated and traffic could easily be diverted on to other large streets, especially those to be widened. Let us address the five numbered arguments individually.

1) Lincoln Park has too many retail areas for a community so close to the Loop. How many retail areas are too many? Virtually every neighborhood in Chicago has a retail strip, some large, some small. The idea of actually turning away potential business development occurred in no other area aside from Lincoln Park. It makes sense only if the residents are trying to create something akin to a suburban subdivision, which it seems was the goal.

2) Michigan Avenue brought loop retail shopping and business offices even closer to the Lincoln Park area. The Michigan Avenue shopping district is, at very least, a mile south of Lincoln Park. Like the State Street shopping district, Michigan Avenue differed in character from Lincoln Park, as did the nature of businesses in these areas.

3) The electrification of the surface lines made access to the Loop easier. Street railways had been operating in Chicago since the 1860s. They made access everywhere easier, and their electrification is irrelevant. Also, nothing is closer or more convenient than walking to work or to shop. If the desire of the LPCA was to generate more pedestrian traffic, local businesses would have to be accessible to local residents by foot.

4) The use along the streets (sic) frontage were not carefully planned. This argument is best of the lot. As was stated earlier, when Ogden was extended, it was cut through the grid with little thought, and no planning. Very few buildings fronted onto Ogden; mostly it was a mess of pavement, shorn buildings, and garages. The street was never developed to its full potential. However, this argument is a reason to invest in and improve the street, rather than remove it.

5) The expected traffic never materialized; possibly because the area already possessed too many main traffic arteries. The expected traffic never materialized for more reasons than one, especially this one. It has less to do with the existence of an abundance of other streets as it does to the way Ogden linked to other high-capacity roads. The terminus of the street at Armitage and Clark is a perfect example. When Lake Shore Drive was extended in 1933, north from Fullerton Avenue as a limited-access highway, Ogden was not linked to it. Lake Shore Drive has exits at North Avenue and Fullerton Avenue, one mile apart. Armitage/Clark/Ogden is half way between the two aforementioned exits. Fullerton, though it is a “mile street”, was a two lane residential road. In fact it was kept this way between Clark and Lincoln as part of the GNRP, as it remains to this day. Between Lake Shore Drive and Clark Street, Fullerton is slightly less narrow, and is often congested. If an exit from Lake Shore Drive had been built at Ogden instead of one or both of the North and Fullerton exits, traffic could have been funneled to the higher-capacity Ogden. A similar preference by the city for narrow, traffic-clogged mile streets over the wider Ogden will resurface in a 1990 study.

Another reason for Ogden’s under-use was the increased use of limited access expressways and freeways, but only because Ogden was poorly connected to these routes. Of the three major expressways/freeways that Ogden intersected or came near, Lake Shore Drive, the Eisenhower Expressway, and the Kennedy Expressway, only one northbound ramp onto the Kennedy connected Ogden with the system. With only one connection, it is easy to see why the street was under used. For example, Goose Island is very close to the Kennedy Expressway. Division Street is the shortest link between Goose Island and the Kennedy, and Division has on-ramps and off-ramps going in both directions. It is the obvious choice for northbound and southbound truck traffic to and from Goose Island. If Ogden had full on and off-ramps from the Kennedy, it would make sense that most southbound trucks from the Island would have used Ogden rather than Division.

That is just one example, not to mention the complete lack of on and off-ramps to the Eisenhower. The Ogden improvement predated modern Lake Shore Drive by one year, and the Eisenhower by twenty-six. Why the connections were never made is an interesting question. The use of Ogden as a carrier of long range traffic southwest of the city diminished with the opening of two expressways, the Stevenson and the East-West toll-way, pushing Ogden further towards obsolescence.

In Lincoln Park, there were claims that the street was something of an eyesore, as it was a massive swath of concrete with no trees or greenery. . It was also felt that it separated the community, however, not everyone in the community was in favor of closing the street. The most active opposition came from the Lincoln Park Chamber of Commerce. The LPCA’s plan made little provision for displaced merchants, planning only for a small shopping area at the corner of Larrabee and North Avenue. The closing of Ogden also necessitated the widening of North Avenue to accommodate increased traffic . North Avenue was a dense commercial district, and its widening would displace even more business owners in addition to those on Ogden. It was also proposed to close a portion of Lincoln Avenue and give it the same treatment as Ogden. The LPCC took action and commissioned the architectural firm of Holabird and Root to provide an alternate design plan that would retain Ogden and Lincoln while improving them.

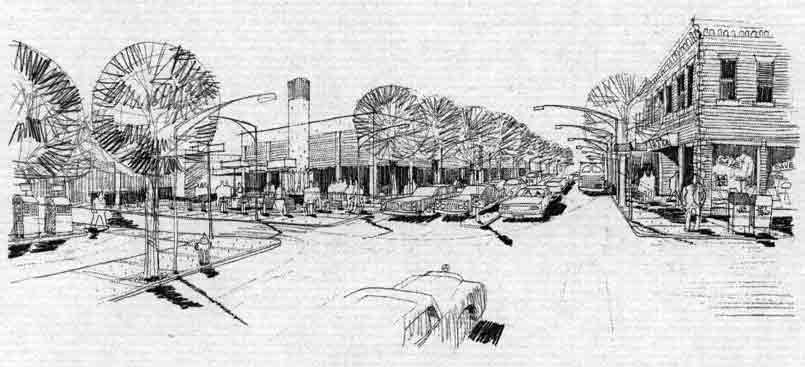

The two different design plans for Ogden offer two very opposite courses of action. LPCA’s plan, designed by the firm of Sasaki, Dawson, DeMay, and associates, called for the street to be closed in favor of a landscaped pedestrian right of way. New parks and open spaces as well as commercial space were provided. The Chamber of Commerce’s plan, designed by the firm of Holabird and Root, makes provision for the street to be retained and beautified while allowing for new residential and commercial zoning.

The design objective of the Sasaki plan was to create meeting places for people which physically reunite the community. The report claims that Ogden was a divisive liability to the neighborhood. By removing it and placing a pedestrian mall with parks and open space, it was hoped that this would have a similar effect for the community as stitches would for a bad cut. A number of recreational facilities and other amenities were to be provided, such as; “conversation plazas”, parking areas, play lots, passive space, bicycle and bridle paths, tennis courts, space for an outdoor art fair or museum, and shopper-oriented recreational areas. It was also hoped that small businesses like coffee shops, small theatres, and distinctive shops would open. The latter refers to an area near the Clark/Armitage intersection that would come to be known as the Ogden Mall.

City of Chicago

City of Chicago

The Ogden Mall was one of two areas provided for in the LPCA plan to be used for retail space. Shops in this area were to be two floors. The small business owner would live on the second floor and operate the business at ground level. There was another retail area planned at Larrabee and North, but like many aspects of this plan, never materialized after the street was removed. As ambitious as the plan was in terms of providing community services, it mostly provided opportunity for developers to build town homes. The Ogden Mall is the only true open space and commercial area constructed on the former right of way. The rest of the right of way currently consists of (mostly) town homes, two churches, an oddly shaped concrete park, another concrete path with benches fronting town homes, and a parking lot. A fenced in space of open grass was left in front of St. Michael’s church.

The Holabird plan recognizes all of Ogden’s flaws more accurately than the Sasaki plan, as well as recognizing that it had assets. The objective of the plan was to retain the street and improve it. This would have involved creating a traffic circle at the Armitage/Clark intersection while extending Ogden to Stockton drive. Stockton parallels Lake Shore Drive and leads traffic to entrances. This would have greatly improved the usefulness of Ogden. The plan also calls for all of the intersections with Ogden by Lincoln Park’s residential streets to be reconfigured. Smaller streets would have been cut off, as in the Sasaki plan, while traffic would be allocated to Ogden via collector streets such as Sedgwick and Orleans. Ogden would have been landscaped on the side walks and with a planted median , addressing the widespread criticism that it was a concrete eyesore. Also, the Holabird plan recognized that “…access…will become more important with the trend of shoppers to use automobiles”. This statement would become prophetic when Lincoln Park would later see a surge in population density and commercial activity.

The Sasaki plan addresses traffic in a more unrealistic fashion. It was stated that “increased pedestrian flow is expected on North avenue”. In order to remove Ogden, North avenue would have to be widened to handle extra traffic. In addition, North avenue as well as LaSalle street were identified by the GNRP as two of the major preferential traffic arteries (principal arterials) through Lincoln Park and Old Town. To widen North avenue to fit this purpose, the commercial facilities on its north side were removed. They were not replaced. If one of the goals for removing Ogden is to separate pedestrian traffic from vehicular traffic, why does the Sasaki plan state that more pedestrian traffic is expected on another main vehicular artery?

Sasaki plan.

Perhaps this pedestrian traffic was to come from the former Ogden right of way, and filter out through the gateway of the planned commercial area at Larrabee and North. But again, that commercial area was never built. Even so, it is incongruous with the rest of the plan and makes little sense. The Ogden Courts town homes instead were built where the commercial area was planned. These homes are designed in a manner not to front on the North/Larrabee intersection, rather they appear as if they are turning their backs to it. It must also be noted that the former Ogden right-of-way is not contiguous or walkable. It leads one to believe the Sasaki plan was intended for public relations purposes, if anything. After all, it was only executed superficially and left Lincoln Park and Old Town disconnected from the west side.

Ogden was removed north of North avenue in 1967. Severing the connection between Lake Shore Drive and the interstate system, the massive viaduct was left to carry sparse traffic through an area few wanted to traverse. In 1958, fifteen public housing buildings of seven, ten, and nineteen stories were constructed at Division and Sedgwick streets. Another eight buildings were added to the complex, fifteen and sixteen stories tall, in 1962. The 1962 addition was situated east of Ogden on the north side of Division, extending east toward previous public housing efforts.

These high rises, known as Cabrini-Green, were comprised largely of poor African-Americans and early on were plagued by crime, drug, and high-vacancy problems. The hopelessness and poverty that came to be associated with this area were a far cry from the ideal that Lincoln Park community leaders were trying to achieve. As writer Greg Beaubien puts it, the removal of Ogden “created a barrier at North Avenue between elite wealth in the Triangle District and crushing poverty around Cabrini-Green.” Lincoln Park and Old Town had been successfully isolated by the removal of Ogden Avenue. The Near West side would follow.

In 1983, Ogden avenue was closed between Clybourn and and North avenues. A baseball field, for the Metro-North Career High School was built over the street.

In 1989 the city began a study to evaluate a number of things about the viaduct section of Ogden and surrounding streets. The main goal of the survey, which was completed in 1992, was to determine whether or not to remove the viaduct or rehabilitate and restore it. Five different considerations were made in the survey.

1) Data was collected regarding the trip purpose and destination of vehicles using the viaduct. This was done by collecting license plate numbers and mailing surveys to those drivers. The drivers were also asked what alternate route they would take if the viaduct were to be removed. In addition to the driver survey, traffic counts were done during peak travel hours.

2) Using the driver survey data, the authors of the study determined what impact the re-distribution of traffic would have on the remaining streets if the viaduct were to be removed. The direction and density of traffic were both considered. 3) Capacity of critical intersections was analyzed to evaluate future improvements. 4) Future conditions of land use were taken into account. 5) Cost estimates of both alternatives were compared.The streets that were included in the study are; Halsted, Division, Milwaukee, Clybourn, Elston, Larrabee, Chicago, and North. Each street is classified according to its traffic count and status within the Strategic Regional Arterial System. Streets are grouped into one of four different classifications. A principal arterial street is federally funded and carries a minimum of 15,000 vehicles daily. These streets are intended to supplement freeway systems and carry regional traffic for trips 10 miles or longer. North and Halsted are the principal arterials in this study. Minor arterials are also federally funded, and carry around 15,000 vehicles daily, more or less. Rather than serve long term trips, minor arterials are designed to augment the principal arterial streets. Chicago and Ashland are minor arterials. The remainder of the streets listed earlier are classified as collector streets. Their function is to provide land access and distribute traffic from arterials to the lowest classification, local streets. Collector streets may be federally funded. Ogden Avenue, because of its low traffic count, around 8,000 daily at the time of this study, was classified as a collector street. In comparison, the busiest street in the study, North Avenue, carried 32,000 vehicles daily.

Surveys were conducted during peak A.M. and P.M. hours in October 1989, and again in 1990. The two hours when the study was conducted were 7-8 A.M.

and 4-5 P.M. The viaduct carried 890 vehicles in the A.M. hour and 870 in the P.M. Hour. Ninety percent of the vehicles using the viaduct were automobiles, only 5% were trucks. Eighty five to ninety percent of drivers surveyed lived in Chicago and were traveling to a destination within Chicago. The purpose of trips over the viaduct during rush hours was mostly (85%) for work-related activities. One third of the work related travel was bound for the Medical Center area.

The study falls very short in considering existing and future land use. It focuses solely on Goose Island as a planned industrial district, 30% of which was vacant at the time. The study assumes that this land will be occupied with similar density industrial use in the future, and generate another 2,000 trips daily. Of the three major streets traversing Goose Island, the study predicted Halsted and Division would pick up another 2,000 trips each by 2010, while Ogden, with the viaduct, would only pick up 1,000. This seems difficult to believe, as Ogden was twice as wide as both of those streets, far better suited to carry industrial traffic. This is only a minor issue, as those predictions were not made solely about Goose Island. The problem is that Goose Island is the only region to have its land use considered in the study. Lincoln Park by 1990 had undergone a process of gentrification in the twenty previous years. This process did not stop in 1990, but it seems to have been omitted in the study. The amount of traffic in Lincoln Park in 2007 is greater than this study estimated.

Another aspect of this study that makes little sense is the preference given to Halsted Street as a principal arterial. Streets of this classification are intended to serve long term trips. Halsted, from its beginning at Grace Street south to the Eisenhower Expressway (and beyond), is quite narrow. Additionally, it traverses a very dense area and features at least three troublesome bottlenecks. The Ogden viaduct was constructed for through traffic to avoid streets like Halsted. The idea that Halsted be preferred is absurd.

All said, the truly telling portion of the study are the cost estimates. The estimate for demolition was $14 million while the estimate for rehabilitation was $39 million. Rehabilitation would have entailed replacement of the bridge deck ($13.5 million), replacement of the electrical system for the bridges ($2.5) million, and repairs to both bascule bridges ($14 million). The rehabilitation cost estimates seem inflated. The idea that the replacement of the bridge deck would be equivalent to the cost to demolish the entire structure seems incorrect. Worse, the study assumes that both bascule bridges need to be fully operational. The Chicago river forks around Goose Island, but only one section at best needs to be passable for larger vessels. One of the bridges could have been turned into a fixed bridge, greatly reducing costs. The study does not even address the necessity for clearance under the bridges. The Chicago River had seen a major decline in heavy traffic as far north as Goose Island by 1990. Perhaps both bridges could have been fixed, perhaps not, the point is that no such alternatives were considered. The conclusion of the study was to remove the viaduct.

On Tuesday, March 24, 1992, the Bridge Maintenance division of the Department of Transportation received an emergency call. Pieces of concrete were reportedly falling from the viaduct near the intersection of Halsted and Division. The viaduct was immediately closed and tradesmen began scaling remaining pieces of loose concrete. During this process, workers were fired upon from the nearby Cabrini-Green high rises. This was not the first time City workers had been shot at from these projects. A proposal was set forth to remove the northern viaduct entrance from Evergreen Street and a portion of the viaduct extending south to the river.

At the time of closure, the structure was reported to be in very poor condition. The roadbed suffered from deep cracks and holes, in addition to the falling concrete. The closure was discussed with property owners in the area and the local alderman, who agreed the viaduct should be removed immediately. Inter-office correspondence between City officials and engineers reflects the same attitude, that the viaduct was useless and should be removed. Then Acting Commissioner of the Department of Planning, Valerie Jarrett, states the apparent uselessness of the viaduct quite well. “The role of Ogden Avenue as a primary transportation route between the North and West sides of the City diminished significantly following the construction of the City’s extensive expressway system.” She goes on to state the usefulness of the route was even further diminished when Ogden was removed north of Clybourn avenue, when

Metro-North Career Academy’s baseball diamond was constructed over the right of way. The Hickory Street ramp, Ogden’s only connection to Goose Island was closed in 1988, she also notes. The viaduct, she states, “is perceived by area companies as a safety hazard and visual detriment to the industrial marketability of Goose Island.” Demolition began in March 1992, and the entire viaduct had been removed by 1993.

As of this writing, Ogden avenue dead-ends before the Chicago river. South of the river to its old terminus at Randolph street, evidence of arguments made against it in Lincoln Park can still be seen. There are a large number of bad intersections with little concrete triangles, and very few good-looking buildings front on to the street. The extension, though a good idea, was not planned well. If intersections had been reconfigured at the beginning, and enough space had been made for retail establishments to front on the street, it may have survived. However, so many mistakes were made in planning and execution, that no other outcome seems possible.

Left: Ron Schramm. Right: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Historic American Buildings Survey or Historic American Engineering Record, HAER ILL, 16-CHIG, 148-1.

Beaubien, Greg. “The Disappearing Street.” Chicago Reader 26 Nov. 1993: Section 1: Our Town.

Bingel, Audrey S. Letter to Burton Natarus. 29 May 1983. Special Collections,

Lincoln Park Conservation Association. Richardson Library, DePaul University, Chicago.

Bowly, Devereux Jr. The Poorhouse: Subsidized Housing in Chicago 1895-1976. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1978.

Burnham, Daniel H. and Edward H. Bennett. Plan of Chicago. Chicago: The Commercial Club, 1909.

City of Chicago, Department of Transportation, Office of Highways and Bridges. Ogden Avenue Viaduct Study. Chicago: 1992.

City of Chicago, Project Development Report. Ogden Avenue Viaduct Demolition. Chicago: 1992.

City of Chicago: Department of Urban Renewal (DUR). Lincoln Park – Project 1. Chicago: 1961.

Foerstner, Abigail. “Neglected Treasures: One Photographer Is Preserving on Film the City’s Overlooked Bridge Sculptures.” Chicago Tribune 27 Feb. 1994, Final Edition: 22-24.

Handley, John. “Plan to Close Ogden Causes Controversy.” Chicago Tribune 2 Apr. 1964: N1.Hewitt, Oscar E. “Ogden Avenue Link Approved by City Council.” Chicago Daily Tribune 19 Feb. 1919: 17.

Hill, Lewis W., et. Al. Lincoln Park General Neighborhood Renewal Plan. 1962. Chicago: Department of Urban Renewal, City of Chicago, 1967.

Holabird, William and John W. Root. Proposed Ogden Avenue and Lincoln Avenue Redevelopment. Chicago: N.p., 1963.

Sasaki, Hideo, et. Al. Ogden Avenue Design Plan. Watertown, MA: N.p., 1965.

Shojai, Carolyn. “Construction Set for Ogden Mall.” Chicago Tribune 27 Apr. 1969: N5.

“Act This Week on $8,000,000 Ogden Avenue Link” Chicago Daily Tribune 1 Sep. 1929: G2.

“Aldermen Balk at “Zigzags” In Ogden Avenue.” Chicago Daily Tribune 18 Jan. 1919: 5.

“All Want New Avenue.” Chicago Daily Tribune 15 Sep. 1899: 12.

“Link For Two Parks.” Chicago Daily Tribune 25 Jun. 1898: 12.

“Making Chicago Fit to Live In–Start Now on the City Plan.

Chicago Daily Tribune 18 Dec. 1918: 8.

“Ogden Avenue Extension Plan Wins Approval.” Chicago Daily Tribune 4 Dec. 1918: 5.

“Ogden Avenue From Union to Lincoln Park.” Chicago Daily Tribune 13 Jul. 1899: 7.

“Ogden Extension on File.” Chicago Daily Tribune 25 Nov. 1902: 8.

“Open Ogden Avenue Viaduct Linking West and North.” Chicago Daily Tribune 10 Dec. 1932: 6.

“Request Ogden Avenue Closing.” 30 Jun. 1963 Chicago Tribune: N1.

“Start Ogden Ave Work in 60 Days.” Chicago Daily Tribune 17 Jan. 1922: 1.

“Wants Goose Island a Park.” Chicago Daily Tribune 11 Jun. 1909: 11.

“Work Is Started On Ogden Avenue After 50 Years.” Chicago Daily Tribune 9 Apr. 1922: 7.

- Chaddick Institute Promoted Tour: The Exention and Removal of Ogden Avenue on Sunday, August 13, 2023

- The Municipal Device

- South Western Avenue Improvement

- Disconnected Yellow Signs

- Lake Shore Drive Redux