Christopher Holt/Chicago Department of Transportation

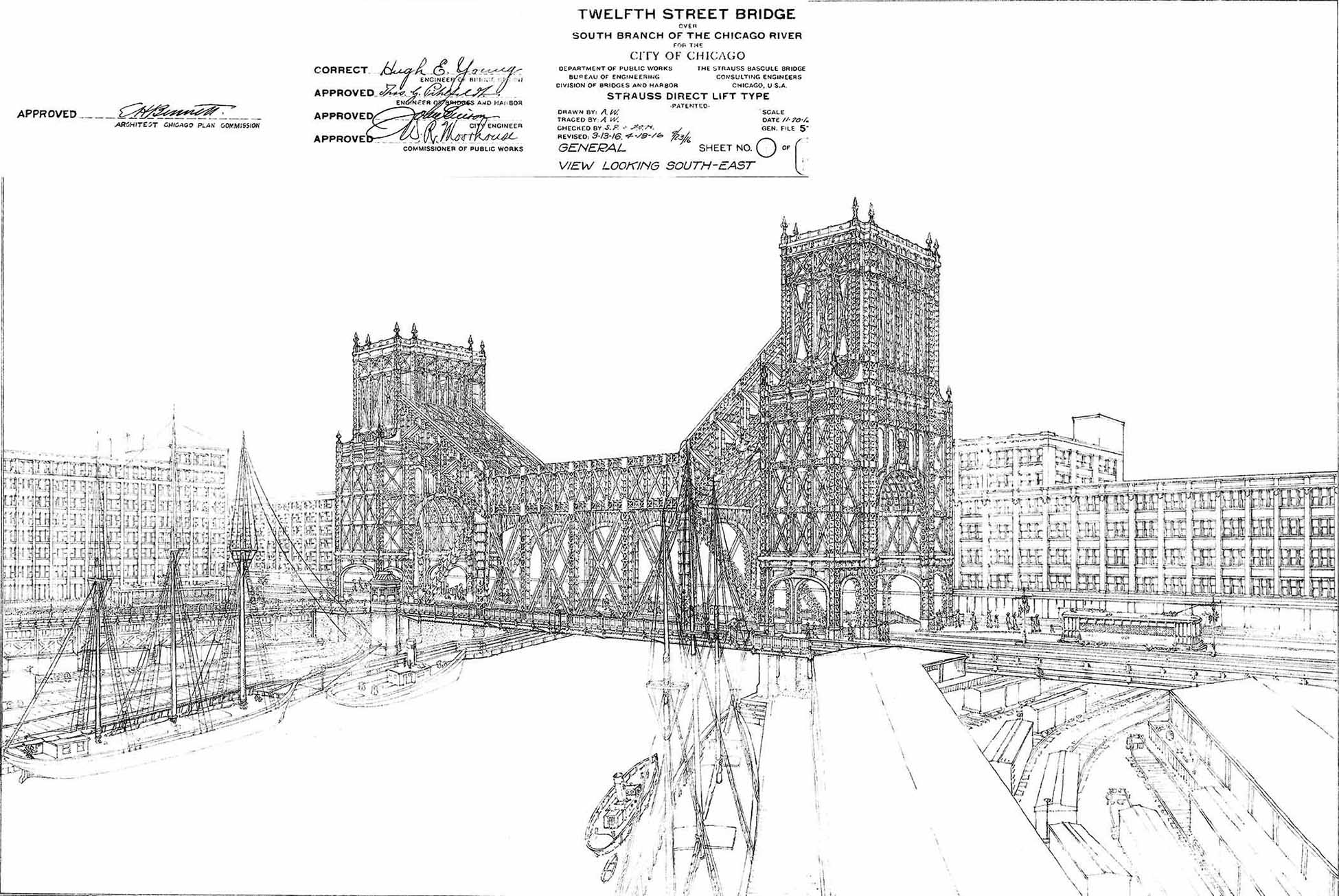

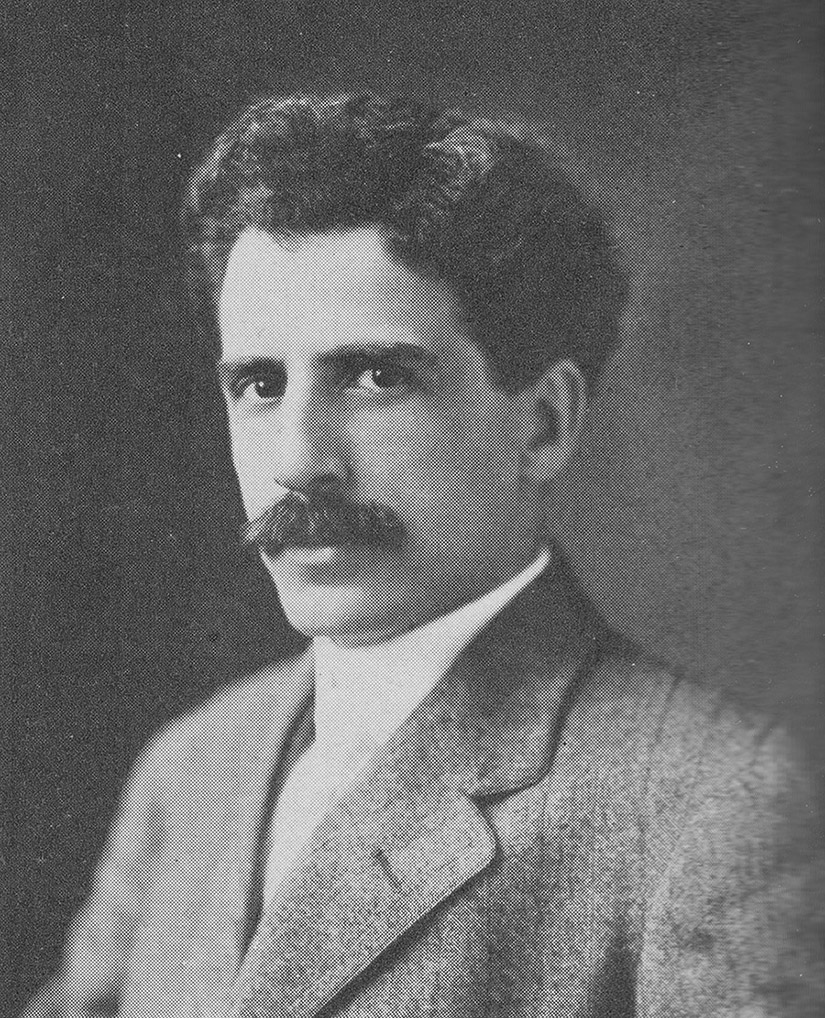

Engineer of Bridge Design since 1899, Alexander von Babo (1854-1920) led the city of Chicago’s Department of Bridges to prepare the renderings shown here and a complete set of more than one hundred structural, fabrication, and construction drawings necessary to build the bridge. It was selected over other designs primarily because the foundation could straddle the rail line of the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad Company along the east bank of the river and the bridge could reliably be moved to cross the new South Branch channel if and when it was straightened. Special reports on temporary steel for the erection of the bridge, member design, vibration stresses, a scheme for moving the bridge, and revised bridge costs were also completed.

In December 1916, the city of Chicago advertised a request for bids to construct this all-steel bridge. The bids were opened on January 10, 1917, but were much greater than earlier estimates – the lowest bid exceeded the city appropriation by 96 percent. European demand for commodities by the end of 1916 had caused a spike in steel prices and prevented the city from awarding the construction contract.

Library of Congress

In 1914, at the age of fifty-nine, von Babo initiated the survey and study to develop plans for widening 12th Street, the viaduct, and bridge following the proposed citywide system of boulevards of the Chicago Plan of 1909. This new boulevard would be part of a series of improvements from the Field Museum to the new Union Station Terminal. The city bridge department developed and/or considered plans for four bridging options:

1. A vertical lift bridge designed by city engineers,

2. Layouts for various bascule bridges designed by city engineers,

3. Plans for a direct-lift bridge submitted by the Strauss Bascule Bridge Company, and

4. Modification of the current swing bridge as a temporary viaduct during the expected straightening of the river channel between Polk and 18th Streets.

Engineering News, 1913

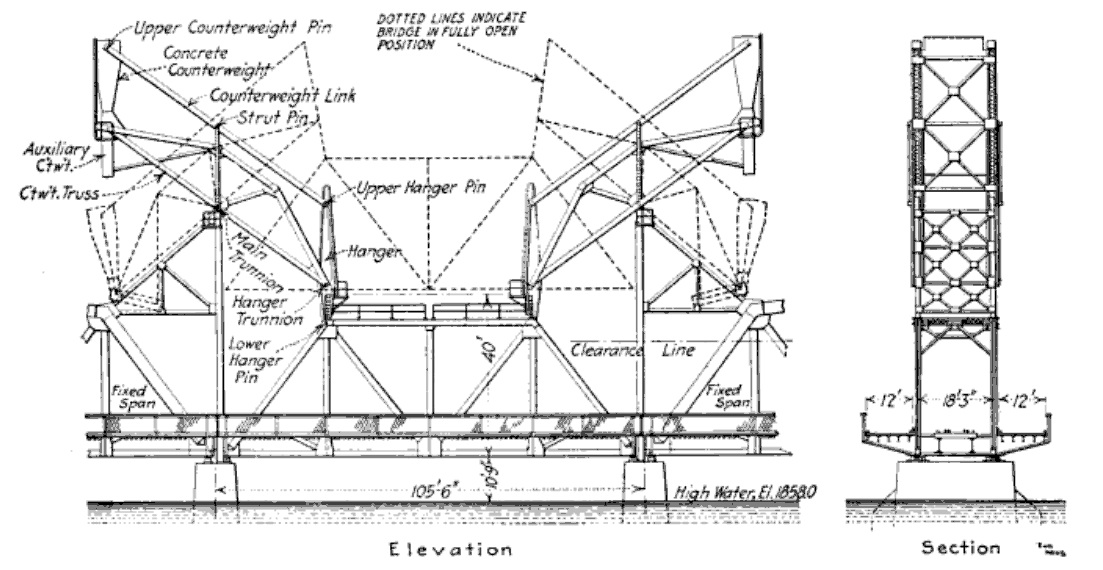

In 1915 the patented Strauss direct-lift bridge (above) was selected. The design provided a simple span 90-feet wide and 241-feet 6-inches between the abutments and operated using a lifting mechanism supported by braced tower posts at each shore to raise the span vertically.

Chicago Daily Journal, 1910 |

In 1902 as a young ambitious engineer, Joseph Strauss (right) founded the Strauss Bascule & Concrete Bridge Company at 104 South Michigan Avenue in Chicago. Born in Cincinnati, Ohio, a few years after completing a degree in mathematics and engineering, he moved to Chicago and became Principal Assistant Engineer in charge of the Chicago office of Modjeski and Angier. Legend has it after firm partner Ralph Modjeski (1861-1940) rejected Strauss’ direct-lift, concrete counterweight bridge proposal he quit and started his own engineering firm. By 1916, Strauss held twenty-two U.S. patents, including eleven for bridge designs.

By this time the direct-lift bridge had gained momentum as an alternative to traditional vertical-lift designs. Engineering journals hailed Strauss’ clever lifting principal of parallelograms connecting counterweights and the bridge roadway, and implied that it would prove more reliable than the steel cables method on most vertical-lift bridges. At least four direct-lift bridges were already in use or under construction:

• The Northern Pacific Railroad Bridge near Tacoma, Washington over Chambers Bay built in 1914.

• The Grand Trunk Pacific Railroad Bridge at Fort George, B.C. Canada over the Frasier River built in 1914.

• The Louisville and Portland Canal Bridge in Louisville, Kentucky first operated on June 23, 1915.

• The Pretoria Avenue Bridge in Ottawa, Canada over the Rideau Canal opened on November 2, 1917.

(A double-deck version of this design was even considered at Lake Street over the South Branch of the Chicago River to replace a double-deck swing bridge.)

Left: Patrick McBriarty Right: Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago

However, additional factors conspired to oppose the direct-lift design. First, it was best suited for long span, relatively low clearance bridge applications and Chicago River traffic usually required relatively high clearances of 100 to 150 feet. Second, civic, architectural, and beatification groups opposed the vertical-lift and direct-lift bridge designs as “ponderous and unsightly.” These civic groups collectively known as the City Beautiful Movement wanted bridges to incorporate better architecture, not obstruct views, and embody art and beauty toward uplifting the general public. These groups successfully blocked a planned vertical-lift design at Lake Street, which received a double-deck, Chicago-type bascule bridge in 1916. Third, a much more pleasing Strauss patented, bascule bridge was built the same year at Jackson Boulevard. It too employed a parallelogram, but with a below-deck counterweight lifting mechanism creating a compact, more streamlined bridge profile. Lastly, that year Hugh E. Young (1883-1951) at 32 years old was appointed Engineer of Bridge Design even though Alexander von Babo continued his employ with the city’s bridge department. A generational changing of the guard also may have contributed to scuttling the plans for this bridge.

On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson addressed both houses of Congress and requested a declaration of war against Germany, which indeed passed two days later. America’s entry into World War I demanded more steel, further increasing prices and making it near impossible to procure steel for anything but the war effort. It was clear the all-steel bridge and viaducts, crossing fifteen rail lines on the west bank of the river and five rail lines to the west, were no longer practical or economical at 12th Street. Although in December 1917 final plans for the 12th Street improvement still called for a direct-lift bridge, city engineers went back to the drawing board and developed plans for both a single-leaf and double-leaf Chicago-type bascule bridge. The double-leaf design was chosen and eventually constructed.

Following the death of former President Teddy Roosevelt in 1919, 12th Street was renamed Roosevelt Road in his honor. Today’s double-leaf Chicago-type Roosevelt Road Bridge opened on November 22, 1930, sealing the fate of the planned Strauss direct-lift bridge as “the bridge that never was.” Today’s Roosevelt Road Bridge operates several dozen times a year, mostly during the spring and fall bridge lifts scheduled for Wednesdays and Saturday or Sunday mornings.

Engineering News, “Direct-Lift Drawbridges without Cables,” June 5, 1913, p. 1168-71.

Engineering Record, “Direct-Lift Span Provides 55-Foot Clearance Over Louisville and Portland Canal,” August 14, 1915, p. 199-200.

The Contract Record, “Pretoria Avenue Lift Bridge, Ottawa,” April 16, 1919, p. 355-6.

McBriarty, Patrick, Chicago River Bridges, University of Illinois Press, 2013.

The New York Times, “Steel Prices Go Up; 1917 Buying Begins,” October 1, 1916.

The Railway and Engineering Review, “A New Type of Vertical Lift Bridge,” April 26, 1913, p. 390-1.

Young, Hugh E. “Problems Encountered in the Design of 12th Street Bridge,” Engineering World, July 1, 1919, p. 17-26.

- Bridgeport’s Chicago & Alton Railroad Bridge

- Railroads and Chicago Swing Bridges

- Bridge Out For Good

- South Western Avenue Improvement

- Old Addresses