In articles, during presentations, and on tours, Forgotten Chicago aims to bring attention to the careers of little-known design professionals who made a significant, if little remembered or studied, contribution to the Chicago area’s built environment. Perhaps no modernist Chicago architect and designer better exemplifies forgotten than James F. Eppenstein (1899-1955).

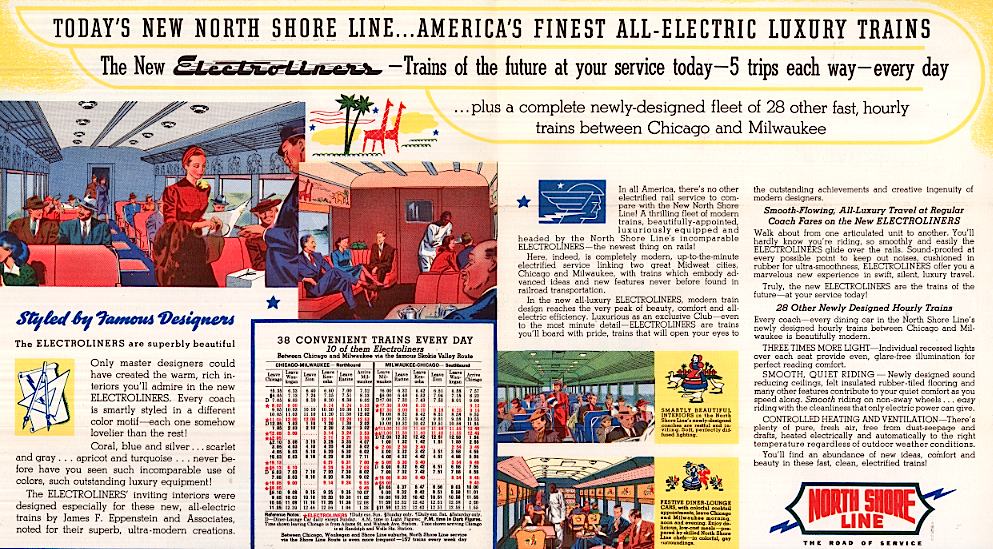

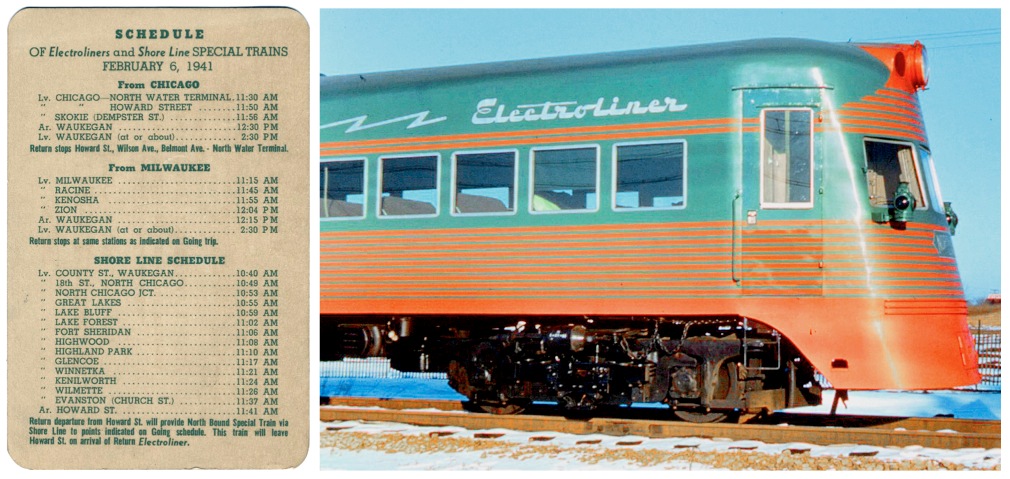

Eppenstein’s work was referred to in both our FC175 event celebrating Chicago’s 175th birthday in March 2012 and our June 2013 article on South Side Shoreline Motels. In a career of just 30 years, Eppenstein would design everything from the interior and exterior of a distinctive train for the North Shore Line Railroad seen above to single-family homes, commercial buildings, and remodeled interiors of existing buildings for a wide variety of clients.

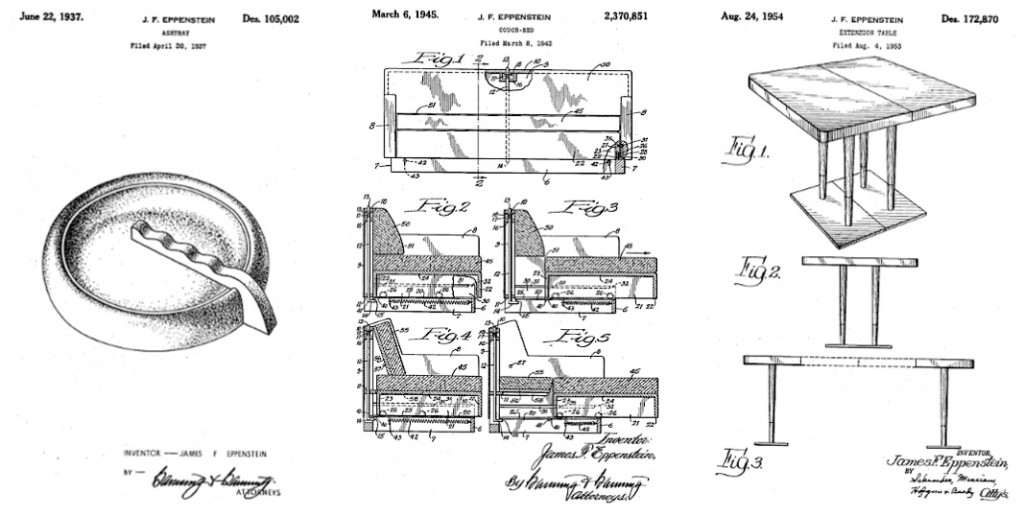

Besides an architect and an interior designer, Eppenstein was a talented inventor and furniture designer. Born in Chicago in 1899, Eppenstein received his Bachelor’s degree from Cornell University at just 20 years old, and went on to attend the University of Michigan, the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, and receive his Masters of Architecture from the Harvard in 1933.2 After working at the Elgin-American Watch Company in Elgin, Illinois from 1919 to 1928, he founded his own architecture and design firm in 1934.3

Utilizing some of Forgotten Chicago’s vast database of images and articles of mostly non-digitized period publications, newspaper archives, and unpublished images housed at a variety of institutions, we have identified 76 building projects designed by James Eppenstein during his brief, but prolific, career. Following is a small sample of some of Eppenstein’s known built works.

Architectural Forum, 1937

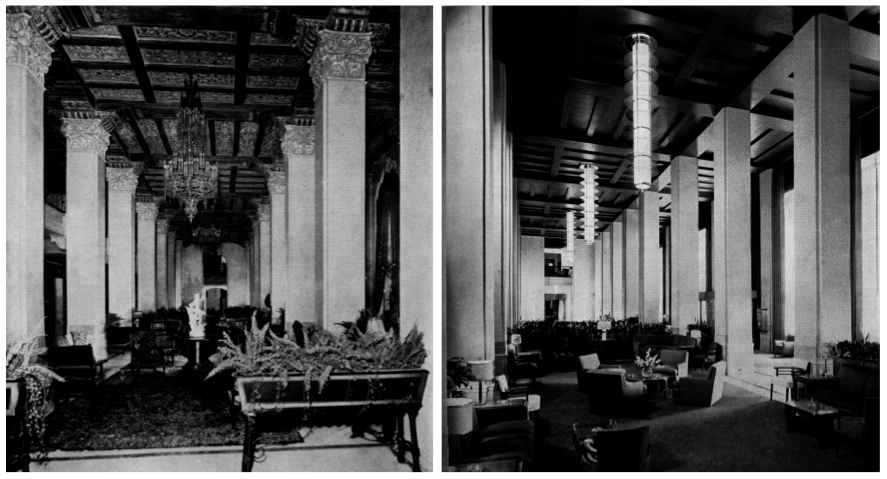

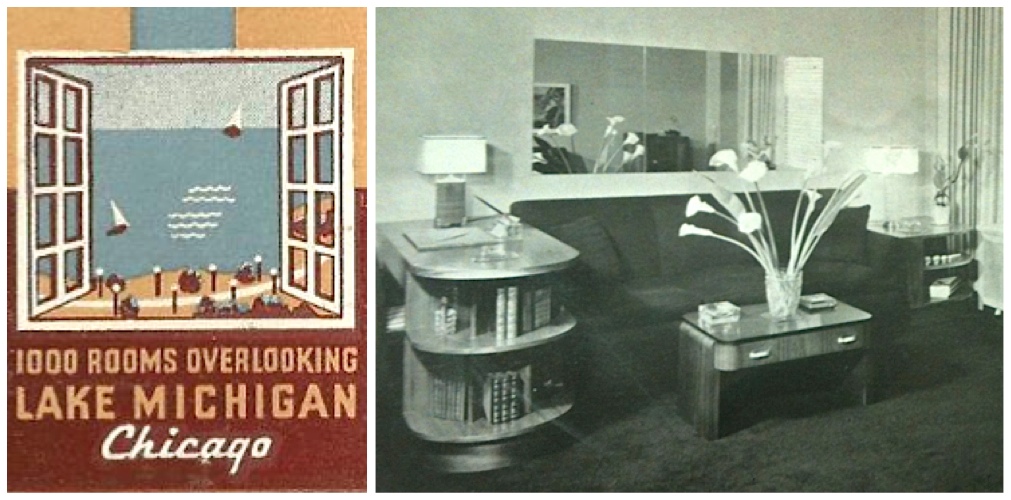

One of Eppenstein’s more notable projects was a 1930s remodeling was for the enormous Shoreland Hotel at 5454 South Lake Shore, seen before and after renovation in the photographs above published in 1937. After decades of neglect, this former hotel has been brought back to its former glory, now as an apartment building, by Studio Gang, who has wisely used Eppenstein’s 1930s remodeling above right and not the hotel’s rather gloomy original lobby design above left.

Architectural Forum, 1937

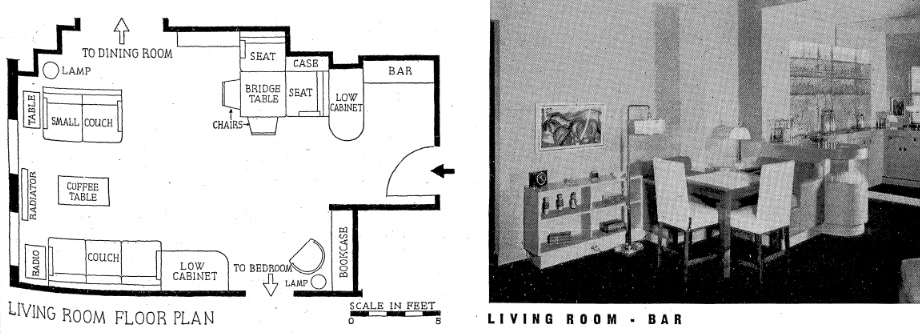

Although the Shoreland Hotel’s past affiliation with criminals and celebrities is extensively noted elsewhere, Eppenstein’s contribution to the remodeling of the Shoreland is seemingly overlooked except by Forgotten Chicago and Studio Gang. Eppenstein’s Shoreland remodeling was documented in contemporary nationally published magazines, including Architectural Forum, seen above. Eppenstein also designed many of the rooms in this hotel; above is a floor plan and photograph of one of these rooms.

Fortune, 1935

Eppenstein and some of his body of work were discovered by the Forgotten Chicago while building a database from non-digitized local and national magazines, as well as library and private collections, containing (as of this writing) over 15,000 images, articles, plans, and ephemera relating to the built environment of Chicago and elsewhere. The Shoreland was originally built in 1926 by architect Meyer Fridstein4, but Eppenstein’s extensive interior remodeling a decade later, including the largely intact lobby, was glaringly absent from the 36-page September 2010 Chicago Landmarks Commission Report.

Left: Chuckman Collection Right: James F. Eppenstein, Architect, Architectural Catalog Co., Inc., 1938

Then, as now, one of the main amenities of the Shoreland are the spectacular views of the lake and skyline, seen below from the northeast corner room on the 12th floor. According to Studio Gang, although the hotel once advertised “1000 rooms” above left there were actually fewer than 800 hotel rooms and suites. The Shoreland currently has 330 apartments.

Patrick Steffes

As with many other extravagant hotels built in Chicago during the booming 1920s, the Shoreland became a financial disaster after World War II. Reportedly built for $6 million in 1926, the hotel was sold in 1954 for only $3 million.5 When the building was sold in foreclosure in 1974, the University of Chicago acquired what had once been one of the most luxurious hotels in Chicago for just $750,000.6 Used as a dormitory by students at the University until 2009, this former luxury hotel was showing signs of its age when the current renovations began.

Patrick Steffes

Although much of the extensive restoration of the Shoreland has been completed, work will be done in the future on the building’s two large public spaces that were not remodeled by Eppenstein: the Louis XVI Room seen above and the Crystal Ballroom. Other former meeting and dining rooms of the building have been restored, and can be used by residents of the building.

Patrick Steffes

As of this writing, the Shoreland Hotel’s current renovation is nearing completion; above is a view of the lobby in December 2013. For the first time in decades, the Shoreland is once again a luxury Hyde Park rental building, with the spirit of Eppenstein’s dramatic lobby remodeling still intact.

For more information on this iconic building, Studio Gang’s Shoreland Hotel page is well worth a visit. This link includes photos and a video of their stunning transformation of this Hyde Park landmark.

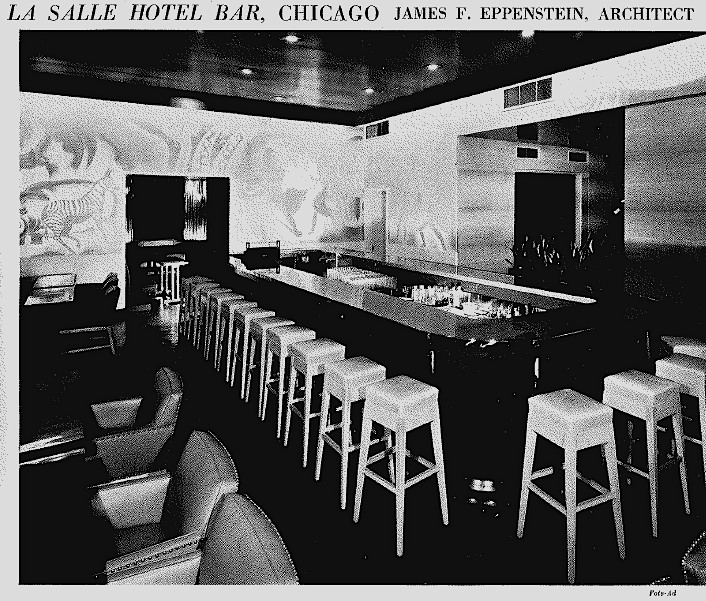

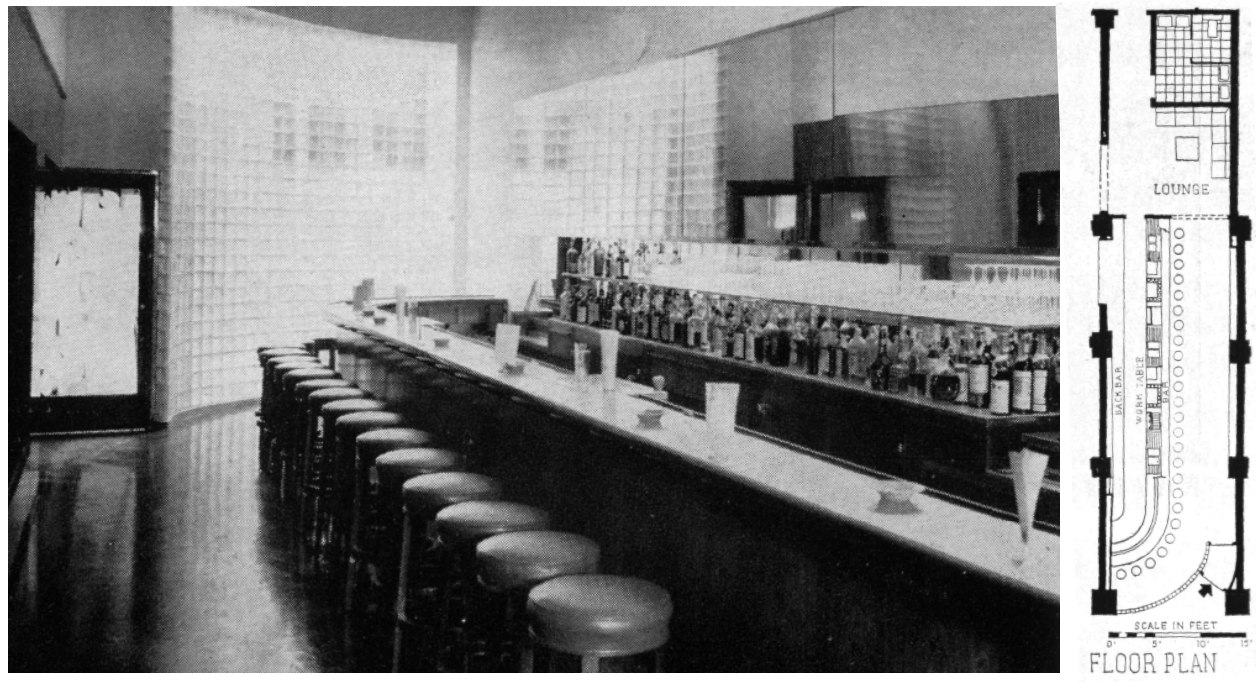

Architectural Forum, 1935

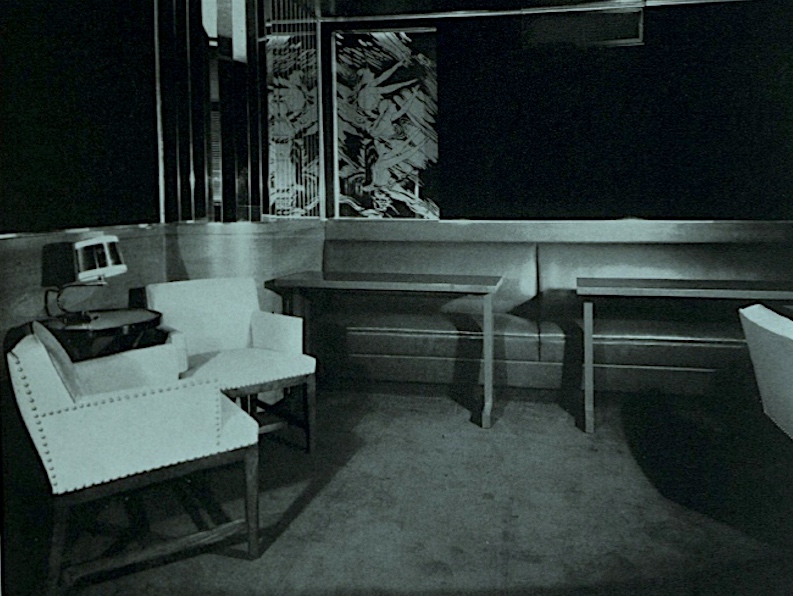

In addition to The Shoreland, Eppenstein remodeled a modest cocktail lounge in what would later become a tragic footnote in the history of another famed Chicago hotel. The long-vanished Hotel LaSalle by Holabird & Roche at 10 North LaSalle had been an important Loop landmark since 1909, and would have been overdue for a freshening by the 1930s. Eppenstein’s swank remodeling included what became a signature of many of his works, a large mural acting as a focal point to the room. Above is Eppenstein’s interior remodeling of the Hotel LaSalle published in 1935; this mural featuring animals was completed by Chicago artist David Leavitt.7

James F. Eppenstein, Architect, Architectural Catalog Co., Inc., 1938

Architectural Forum was enthusiastic about Eppenstein’s street-level bar remodeling in this vast hotel. In a 1935 article, they gushed, “New materials – leather, stainless metals, glass – with quantities of lightness, color and durability adapt themselves so perfectly to the modern bar that they have become as typical of today’s drinking places as the mahogany bar and brass rail of yesterday. In the Hotel La Salle Bar . . . the designer has displayed architectural ingenuity in interpreting these materials with no sacrifice to individuality.” 8

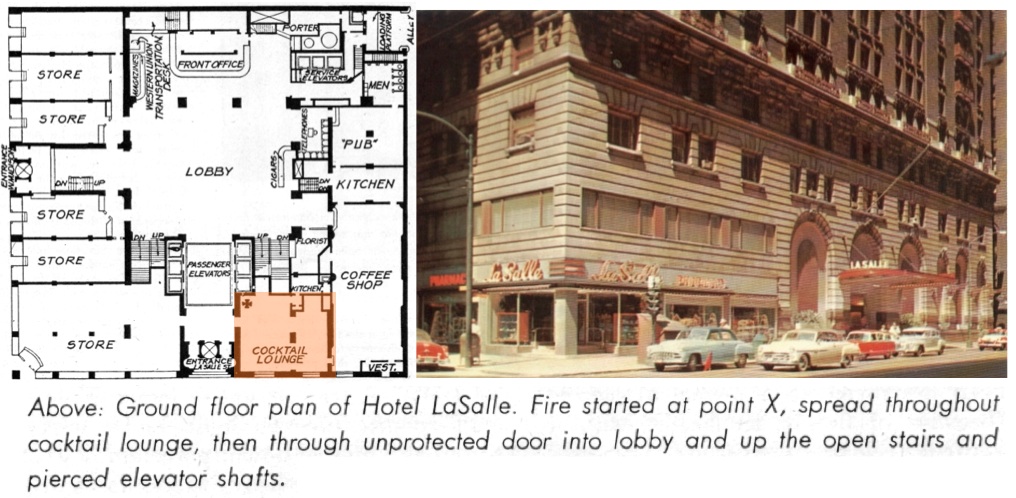

Left: Architectural Record, 1947 Right: Chicago History in Postcards, no date

Eppenstein’s Hotel LaSalle bar (highlighted in the floor plan above left) was the starting point in one of the worst fires in Chicago history. Shortly after midnight on June 5, 1946, a small fire started between what was then known as the Silver Lounge and the elevator shafts; due to a series of design flaws in the hotel, the fire quickly grew and engulfed the hotel’s famed walnut paneled lobby. With fire and smoke spreading quickly through the hotel, 61 people were killed and more than 200 were injured.9

Architectural Record, 1947

According to a 1947 article published in Architectural Record above, the Hotel LaSalle’s devastating fire was believed to have started in the false wall behind the wall of the bar designed by Eppenstein and an elevator shaft,10 just to the left of the zebra seen in the 1935 Architectural Forum photograph. The fire at the Hotel LaSalle, and other deadly hotel fires in the 1940s, would lead to changes to fire safety regulations throughout the country, including Chicago.

After an extensive remodeling and improvements in safety features, the LaSalle Hotel reopened and operated for nearly three more decades under its original name. This hotel closed on June 29, 197611 and was demolished soon after; the current office building on this site was completed in 1979 by Perkins+Will, with the hotel’s foundations reused for the new 26-story building.12

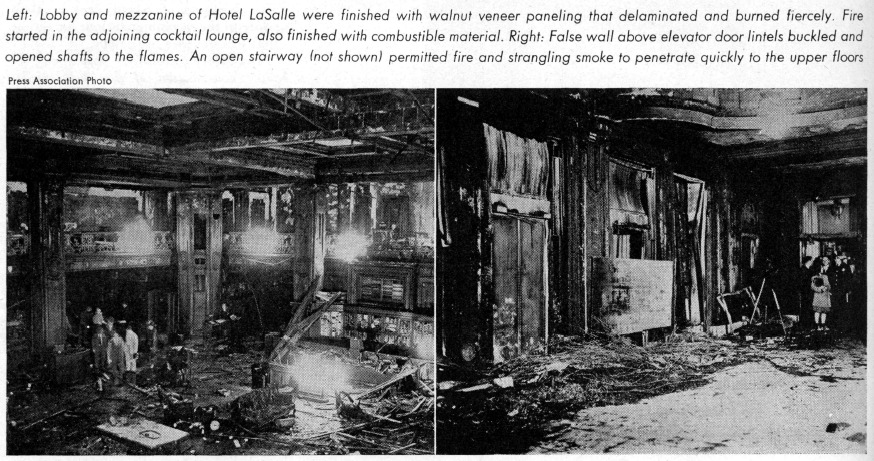

Left: Google Street View, June 2011 Right: Patrick Steffes, January 2014

The site of the Eppenstein’s bar and the start of the LaSalle Hotel fire is currently a bank of Chase ATM machines, seen above left. Chicago, compared with many other cities, has virtually no markers commemorating major disasters, notably fires. In Atlanta, the Winecoff Hotel fire that occurred some six months after the fire at the LaSalle, is remembered in the prominent marker above right.

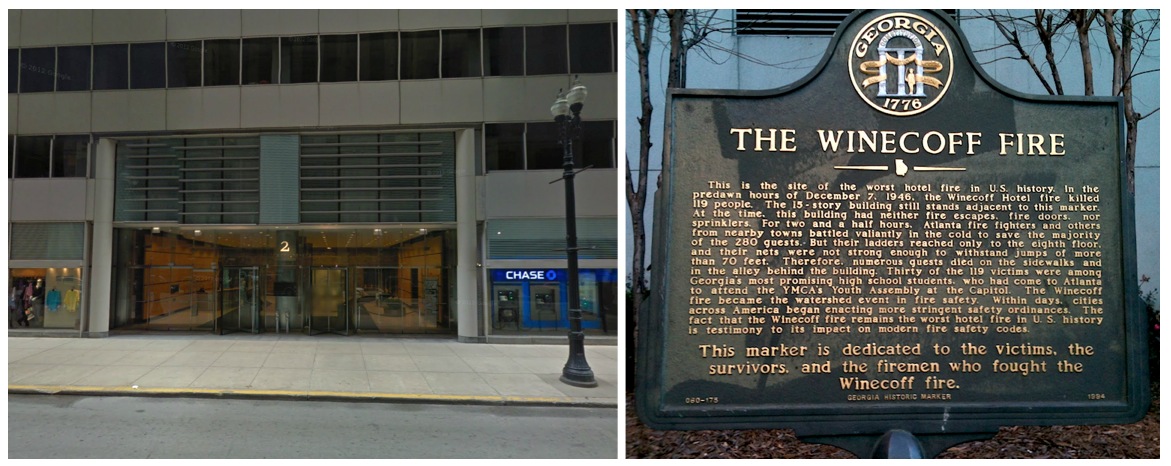

Left: James F. Eppenstein, Architect, Architectural Catalog Co., Inc., 1938 Right: CardCow

Although nearly all of the work by Eppenstein discovered by Forgotten Chicago has been in the Chicago area, he also redesigned a portion of the exterior and interior of the 1927 Roosevelt Hotel in Pittsburgh, illustrated above left in a 1938 monograph published on Eppenstein’s work13. From the street, there was no doubt about the type of business behind this prominent curved glass block wall.

Architectural Forum, 1937

For the Roosevelt Hotel, besides the exterior of the Gentleman’s Bar pictured in the first image, Eppenstein would also design the Roosevelt Hotel’s Coffee Shop and Hideaway Bar,14 seen above top. The bar’s floor plan and Gentleman’s Bar front section is seen above bottom. While the Roosevelt Hotel closed decades ago, the building remains in downtown Pittsburgh, now as a mixed-use building.

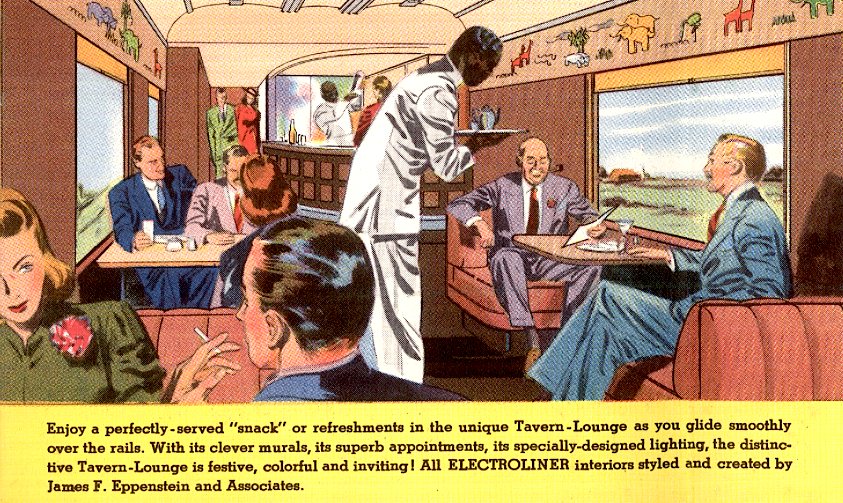

The career of Eppenstein was prolific and diverse. In addition to nationally published projects at two of the largest hotels in the Midwest, he designed the ultra-modern Electroliner trains for the North Shore Line running fast between Chicago and Milwaukee from 1941 to 1963. As exuberantly described in the promotional piece above, the color scheme of the Electroliners was, well, eclectic: “Coral, blue and silver . . . scarlet and gray . . . apricot and turquoise . . . never before have you seen such incomparable us of colors, such outstanding luxury equipment!” Eppenstein’s firm is mentioned in the ad above, at lower left.

J. J. Sedelmaier and www.printmag.com

Just two Electroliner trains would be built. The only restored Electroliner is part of the collection of the Illinois Railway Museum in Union, Illinois. This museum, featuring the largest railway collection in the United States, is well worth a visit. More information and their schedule may be found on the IRM web site.

J. J. Sedelmaier and www.printmag.com

J. J. Sedelmaier and www.printmag.com

With one notable exception, little has been found on Eppenstein’s contribution to this unique inter-urban train serving Milwaukee and Chicago, or on Eppenstein’s career whatsoever. Fortunately, there are many additional rare images of these Electroliner trains in a comprehensive article by J. J. Sedelmaier located here.

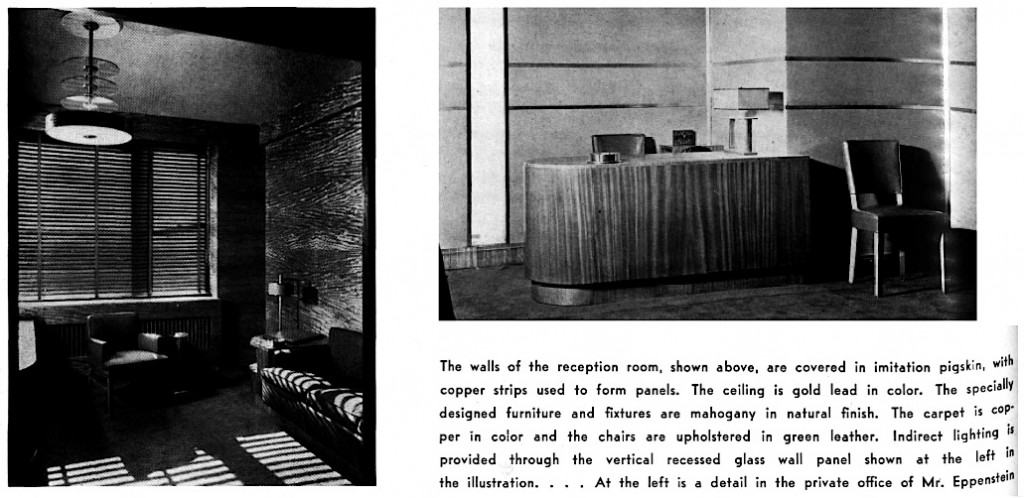

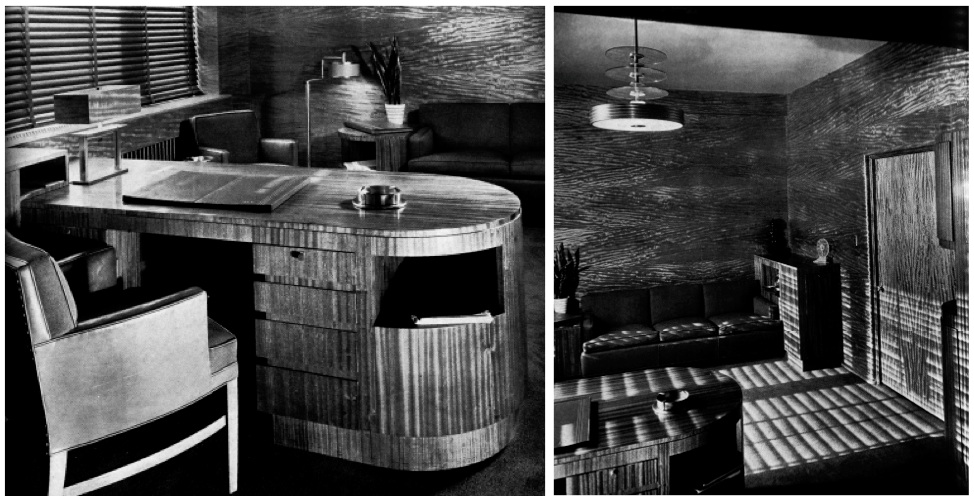

American Architect, 1935

American Architect, 1935

The second Eppenstein project known to be published after the Hotel LaSalle Bar was for his own office. These images were published in 1935 in American Architect, a magazine that would cease publishing three years later.16 For Eppenstein’s office, this magazine exclaimed, “The office of James F. Eppenstein, designed and furnished in the modern manner, is at once impressive.”17 Eppenstein’s office was located in the 35 East Wacker building,18 a building currently home to the Chicago Chapter of the American Institute of Architects.

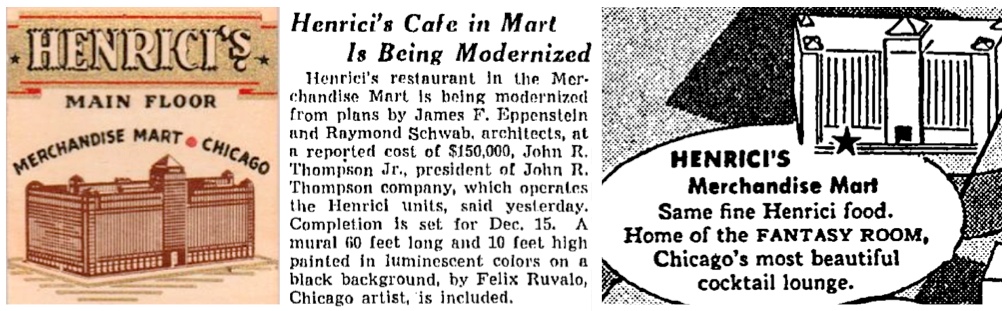

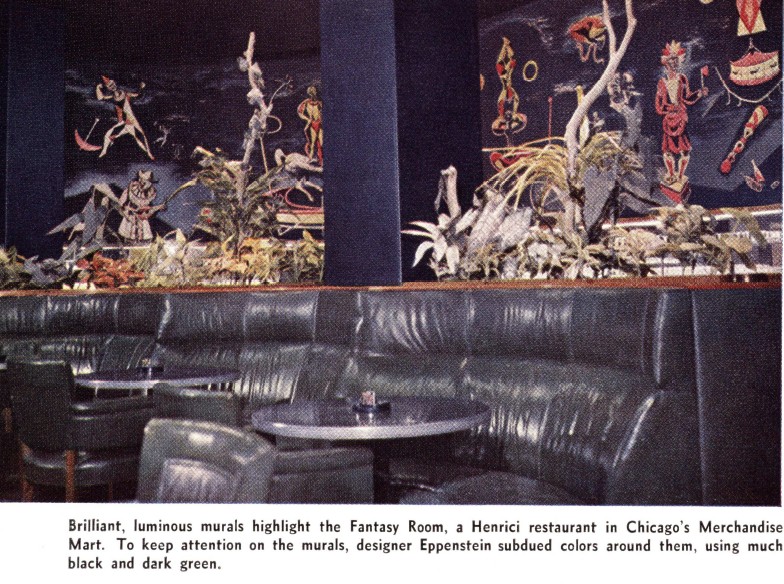

Top Left: eBay Top Center: Chicago Tribune, 1947 Top Right: Chicago Tribune, 1952 Bottom: Institutions, 1953

In part two of this series, we explore Eppenstein’s extensive commercial, retail, and restaurant work. A future article will also look at his residential commissions, including his own 1930s modernist residence on North Astor Street.

2. Who’s Who in Chicago and Illinois, Ninth Edition (Chicago, Illinois: The A.N. Marquis Company, 1950) pg.180.

3. Ibid.

4. Chicago Landmarks Commission Report on Shoreland Hotel; http://www.cityofchicago.org/dam/city/depts/zlup/Historic_Preservation/Publications/Shoreland_Hotel.pdf (accessed July 8, 2013).

5. Shoreland is Sold in Multi-Million Deal. Realty and Building, June 12, 1954, pg. 3.

6. History of the Shoreland Hotel; http://www.hydepark.org/historicpres/shoreland.htm (accessed July 24, 2013).

7. Eating and Drinking: LaSalle Hotel Bar Chicago, James Eppenstein, Architect. Architectural Forum, November 1935, pg. 469.

8. Ibid.

9. Hotel Fire Safety. Architectural Record, February 1947, pg. 105-107.

10. Ibid.

11. LaSalle Hotel to be Liquidated, Demolished. Realty and Building, September 4, 1976, pg. 11.

12. 2 North LaSalle Building; http://www.emporis.com/building/2northlasalle-chicago-il-usa (accessed November 11, 2013).

13. James F. Eppenstein, Architect, Chicago, Illinois. New York: Architectural Catalog Co., Inc., 1938.

14. Ibid.

15. American Architect, December 1935, pages 26-28

16. Periodical collection of Deering Library of Northwestern University; final bound volume is February, 1938.

17. American Architect, December 1935, pages 26-28

18. Illinois Bell Classified Telephone Directory for Chicago. Chicago: The Reuben H. Donnelley Corporation with permission of the Illinois Bell Telephone Company, June 1937.

- Sharply Defined Masses: The Forgotten Work of James F. Eppenstein, Part 3

- Unexpected Glamour: The Forgotten Work of James F. Eppenstein, Part 2

- Chicago’s Shoreline Motels – South

- Bertrand Goldberg in Tower Town Part 3: Bertrand Goldberg’s Michigan Avenue Project

- Bertrand Goldberg in Tower Town Part 2: Postwar Development of Michigan & Pearson