Left: The Economist, 1938 Center: 1854 map of Chicago courtesy Newberry Library Right: Chicago Tribune, 1946

Details of a pre-Great Chicago Fire shipping canal in the heart of the Gold Coast were discovered in early 2014 by Forgotten Chicago, shown above. The Grand Haven Slip was part of a partially-built project planned to connect the North Branch of the Chicago River to Lake Michigan, bypassing the often-clogged Main Branch of the Chicago River. Further details and documentation of this canal have proven elusive, and no mention of this curiosity has yet been found in any books on early Chicago history.

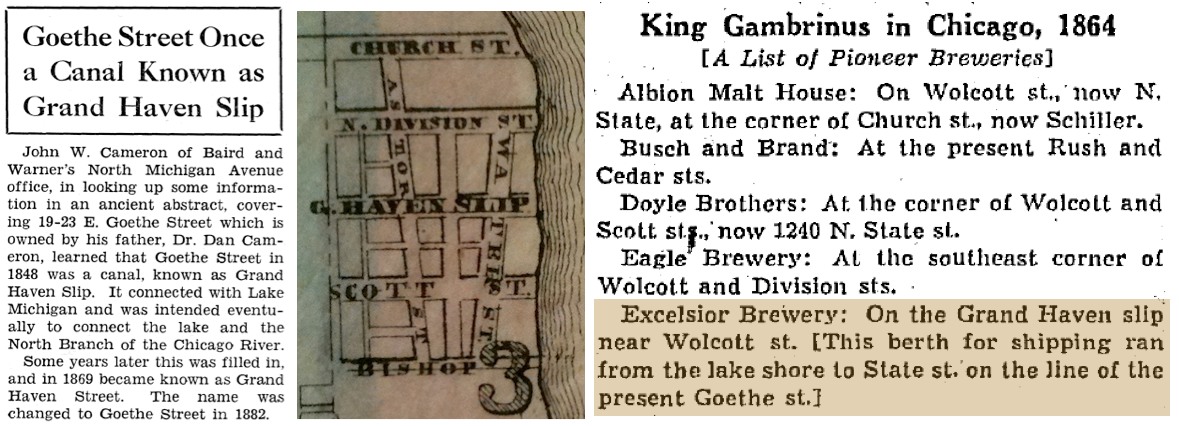

Above left is the story reported in 1938 in the Chicago magazine The Economist (later renamed Realty & Building) that alerted us to the existence of the Grand Haven Slip. Above center is an 1854 map showing the Grand Haven Slip’s location and the names at the time of Gold Coast streets and the slip; current street names from north to south are Schiller, Banks, Goethe, Scott and Division Streets.

Patrick Steffes, March 2014

The Grand Haven Slip was found just four times in the archives of the Chicago Tribune between 1849 and 1990;1 at top right is one of the rare Tribune articles confirming its existence. This article also noted numerous breweries located before the Great Fire in the Gold Coast. Seen above is how the corner of Goethe Street and North State Parkway (formerly Wolcott Street) appears today, with no trace of either the Grand Haven Slip or these early breweries.

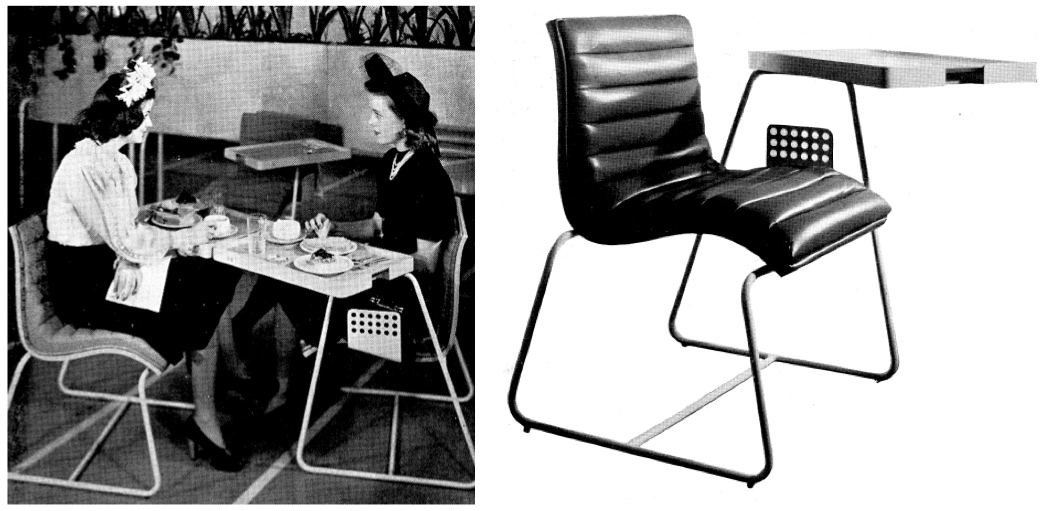

Commerce, 1946

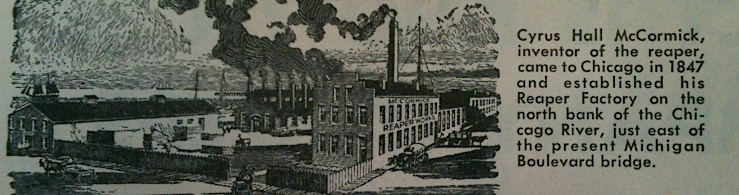

In addition to bygone breweries, Chicago’s earliest factories were built close to the Chicago River and the Loop, in what would later become some of Chicago’s most expensive real estate. Home by the 1920s to the headquarters of the Chicago Tribune, this site on the north bank of the Chicago River and North Michigan Avenue was once home to Cyrus Hall McCormick’s Reaper Works from the 1840s until its destruction in the Great Fire, seen above. In our research, Forgotten Chicago searches for little-seen images of Chicago’s overlooked past to share during presentations and tours.

Left and Center: Chuckman Collection Right: Realty & Building, 1963

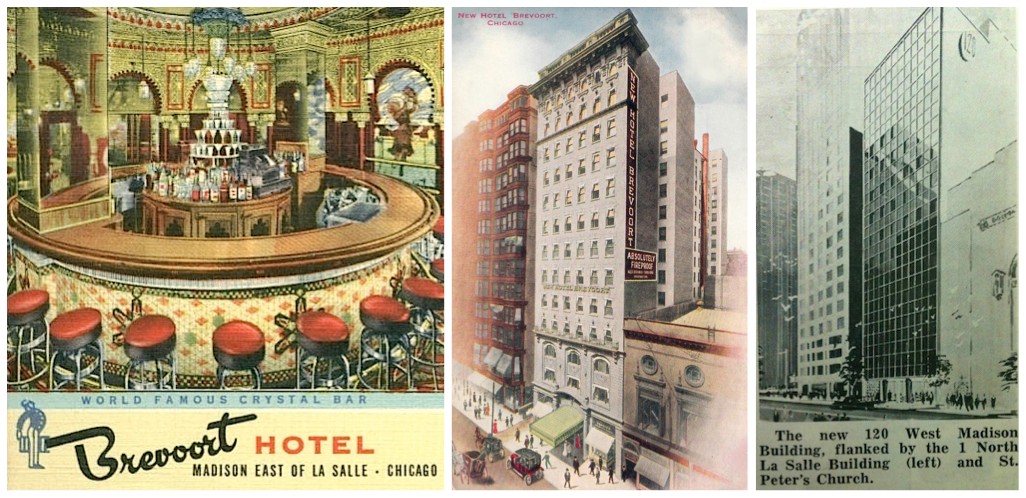

Hiding in plain site in the heart of the Loop is what may be the oldest extant building in Chicago (with the exception of The Congress; see below) built as a hotel. The 1906 former Hotel Brevoort, located at 120 East Madison between Clark and LaSalle was thoroughly remodeled in the early 1960s by the prolific local firm of Shaw, Metz & Associates, seen before and after above center and right, and largely unchanged fifty years later.

Forgotten Chicago discovered the curious tale of this long-vanished hotel and still-standing building while reviewing tens of thousands of pages of non-digitized issues of the local construction, real estate, and development magazine Realty & Building, successor to The Economist. This comprehensive publication is the source of more than 5,000 articles and images in Forgotten Chicago’s vast and proprietary database on the built environment of Chicagoland and beyond, which now contains more than 17,000 images, articles, and ephemera.

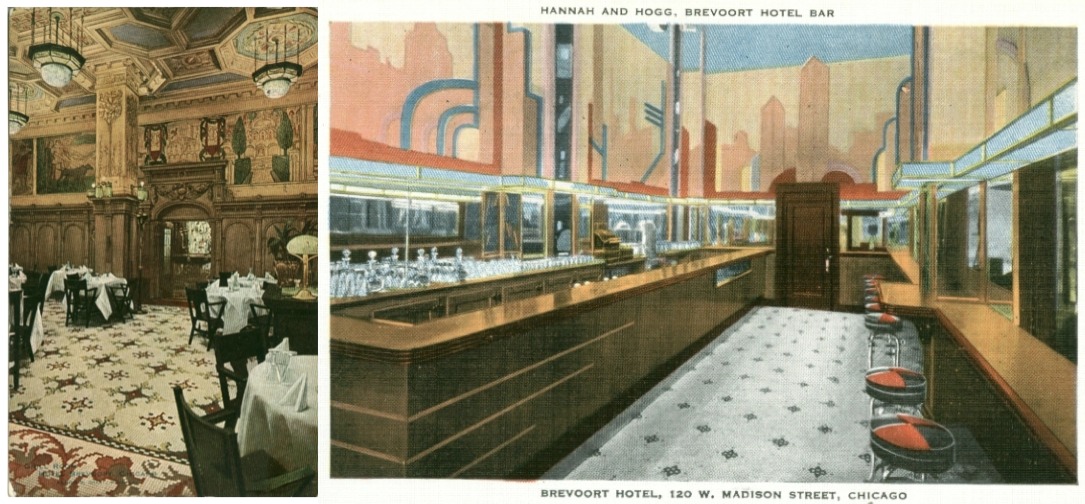

The Brevoort’s 1960s remodeling was not the first change to this venerable hotel. Seen above are two undated images of the hotel’s interior, with the Hannah and Hogg bar remodeled at some point at right in the smart Art Deco style. While the shallow light court and windows on the Brevoort’s east side were removed during its remodeling, windows remain on the west side of this building. It is not known if any of the Brevoort’s lavish interior details survived its conversion into office space more than fifty years ago.

Chicago’s Loop has many more obscure and overlooked buildings such as the former Hotel Brevoort. For the first time in three years, Forgotten Chicago will be reprising our exclusive “Downtown Confidential” walking tour in September, a tour that focuses on re-purposed, abandoned, and forgotten buildings in the Loop.

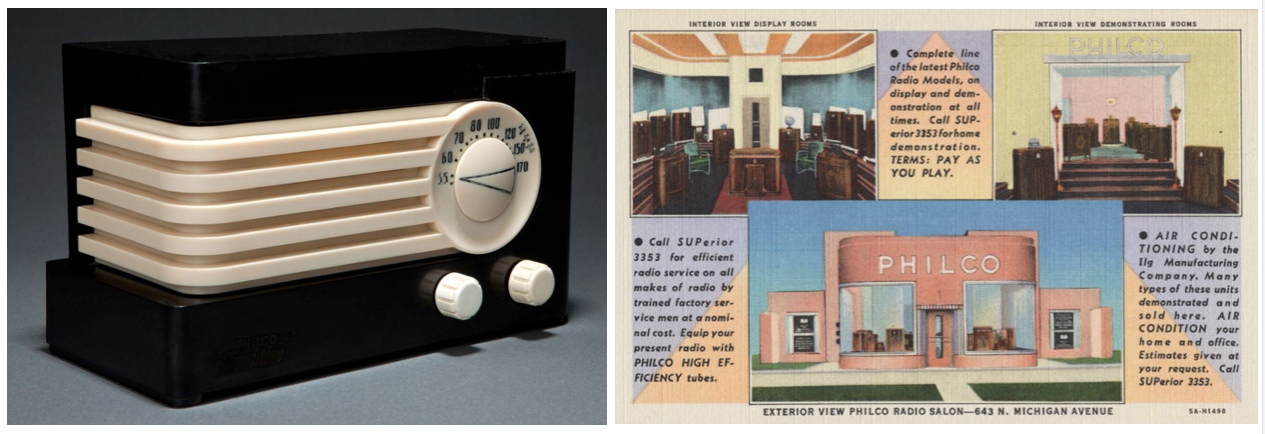

Top: Architectural Forum, 1936 Bottom Left: Decophobia Bottom Right: Illinois Digital Archives

Some seventy years before the Apple Store opened in 2003 to enormous crowds on North Michigan Avenue, this famed shopping street was home to two of the nation’s largest consumer electronics manufacturers. By 1935 Philco, a leading radio manufacturer at the time, had remodeled its Spanish Revival “Philco Bungalow” showroom at 643 North Michigan shown below left into a sleek Art Deco Radio Salon to showcase their latest technology including the 1930s design above left. This forgotten building was by the architectural firm Pereira and Pereira, perhaps best known locally for their Esquire Theatre on East Oak Street, which recently underwent a significant remodeling.

Left: Architectural Forum, 1935 Right: Realty & Building, 1949

Radio was the leading consumer technological advance in the years after World War I, and it was logical for manufacturers to showcase their products on Chicago’s toniest shopping street. Philco’s original showroom above left would have needed a major remodeling to keep current with current styles, which included massive rounded windows to showcase their newest products.

By 1949, Philco had departed their showroom on Michigan Avenue, replaced by Chicago radio manufacturer Hallicrafters, above right. Just north of the former Philco showroom was the old Poole home, purchased by the Poole family in 18572 and rebuilt after the Great Fire, and one of the last remaining single-family homes on North Michigan Avenue.3 The Poole homestead and Philco/Hallicrafter’s showroom were on the southeast corner of Michigan and Superior.

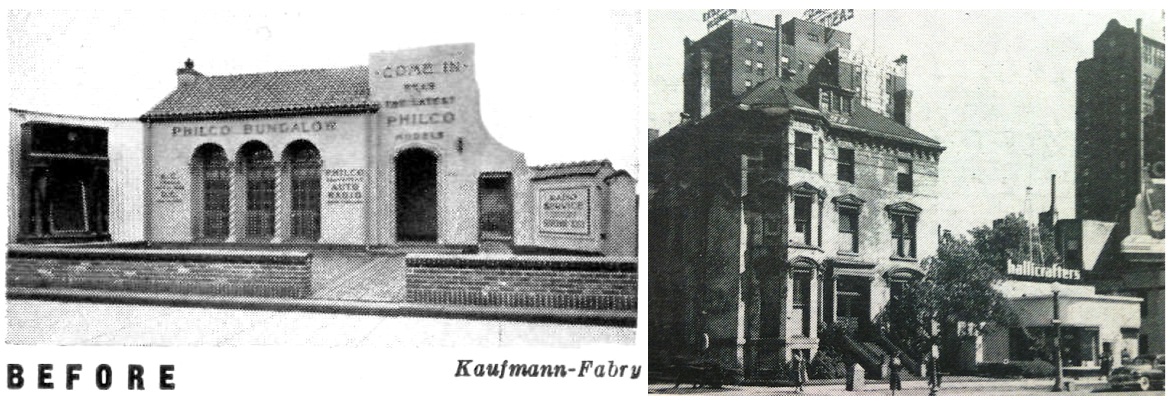

Left: Chuckman Collection Right: Architectural Forum, 1935 Right: Realty & Building, 1949

In addition to Philco, Chicago-based electronics pioneer Zenith in the 1930s also had a prominent showroom nearby on North Michigan Avenue. Seen above are two views of their location at the southwest corner of Michigan and Huron, currently the site of the mixed-use City Place building at 676 North Michigan. Worth noting are the odd changes made from the photograph above right of the building to the 1935 postcard, which changed the number and location of this Philip Maher-designed building’s windows, for reasons unknown.

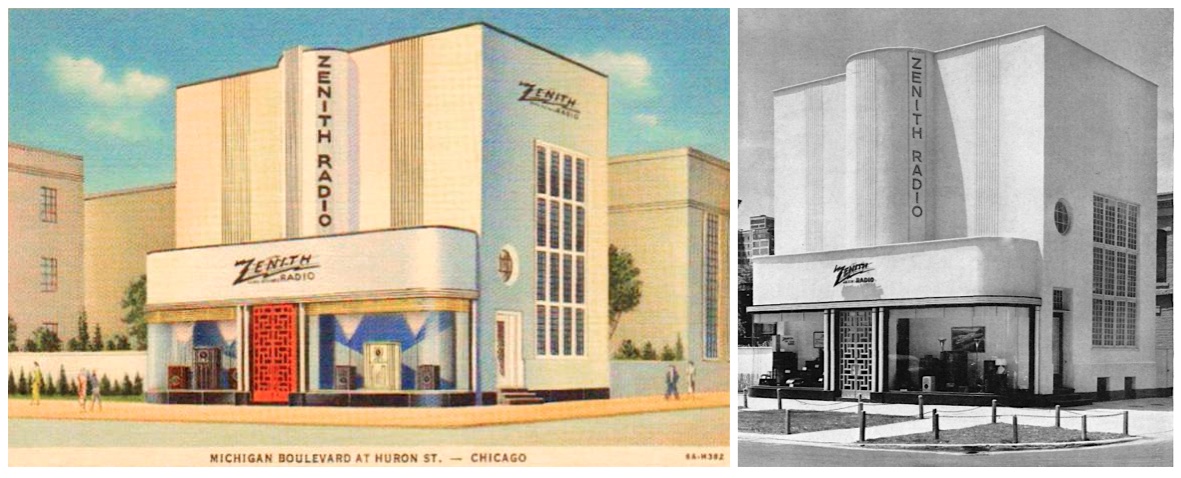

Left: Progressive Architecture, 1959 Right: Smithsonian American Art Museum

Zenith would later leave their Michigan and Huron location and move south of the Chicago River to another showroom at 200 North Michigan; this elegant 1927 building by Holabird & Roche is itself undergoing demolition in 2014. Besides featuring the latest in their consumer products (including state-of-the-art televisions), Zenith also featured a major work by renowned sculpture Harry Bertroia, above left. Bertroia’s sculpture was donated to the Smithsonian Institurion in 1989; a slide show about the restoration of this multi-media sculpture may be seen here.

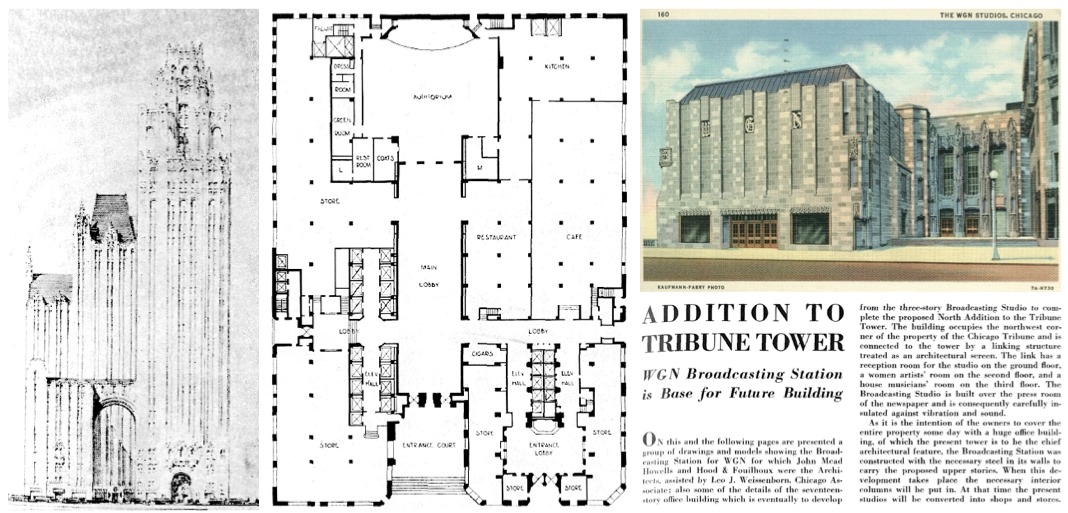

Left, Center and Lower Right: Pencil Points, 1936 Upper Right: Chuckman Collection

Another radio-related project on North Michigan Avenue were the studios for WGN 720 AM, connected to the Tribune Tower and opening in September 1935.4 Less remembered was the proposed future complex planned to eventually rise next to and above this new studio. Although the rendering at far left was published in the Tribune in December 1928, the corresponding article in Pencil Points above describing how the WGN radio studio addition was designed with a future addition in mind would not be published until 1936, above center and right. The imposing addition pictured above left was never built; a more modest addition to the Tribune Tower would be built after World War II.

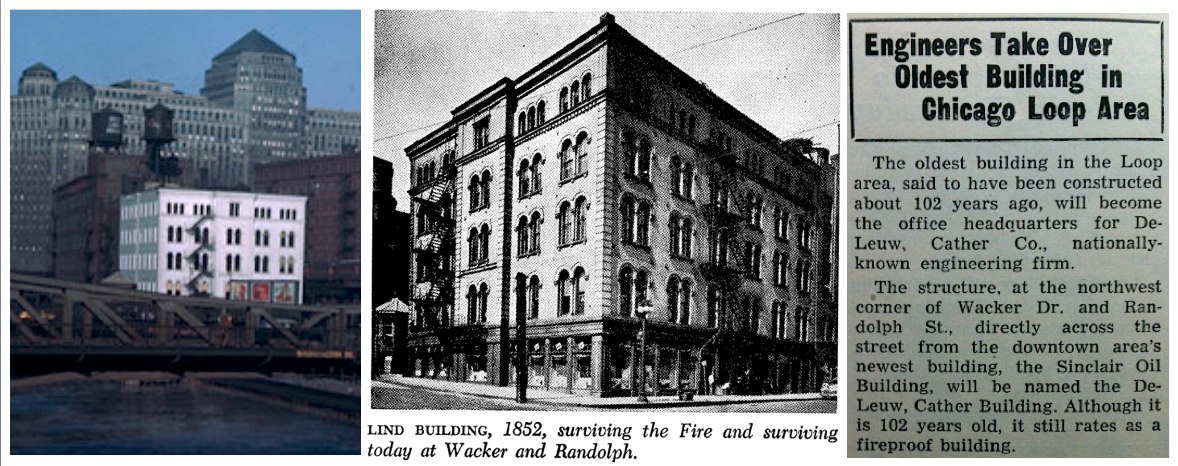

Top: History of Chicago From Early History to Present, 1885 Bottom Left: Charles Cushman Collection, 1944 Bottom Center: Inland Architect, 1957 Bottom Right: Realty & Building, 1954

Since our beginning in 2007, Forgotten Chicago has taken great pride in debunking wholly untrue urban myths about Chicago’s built environment. One of the most persistent untruths is that the Water Tower was the only prominent structure in the central area to have survived the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. In reality, the John M. Van Osdel’s Lind Building (aka Lind Block) seen at top far left post-fire at the northwest corner of North Wacker Drive and West Randolph Street was completed nearly two decades before the Chicago Fire, and survived for more than 110 years. The Lind Block was demolished with little comment or attention in 1963 for the current occupant of this prominent site.

Seen at top far left is the Lind Block post-Chicago Fire; bottom from left to right is the Lind Building seen in a rare color view in 1944, illustrated in an article in Inland Architect in 1957, and mentioned in a 1954 article from Realty & Building noting that while more than a century old, the Lind Building was still classified as fireproof. The other building mentioned in this article, Holabird & Root’s 1954 Sinclair Oil Building at 101 North Wacker Drive, was also demolished years ago. In presentations and during tours, Forgotten Chicago shares little-known facts, stories and images about the Chicago area with our participants.

Commerce, 1949

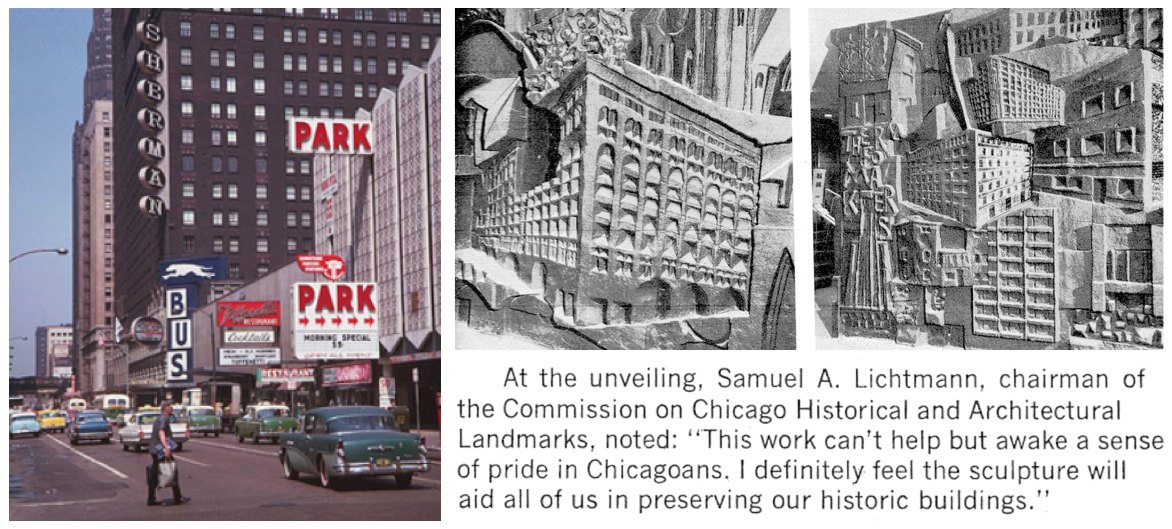

Top Left: Chuckman Collection Top Right and Bottom: Inland Architect, 1969

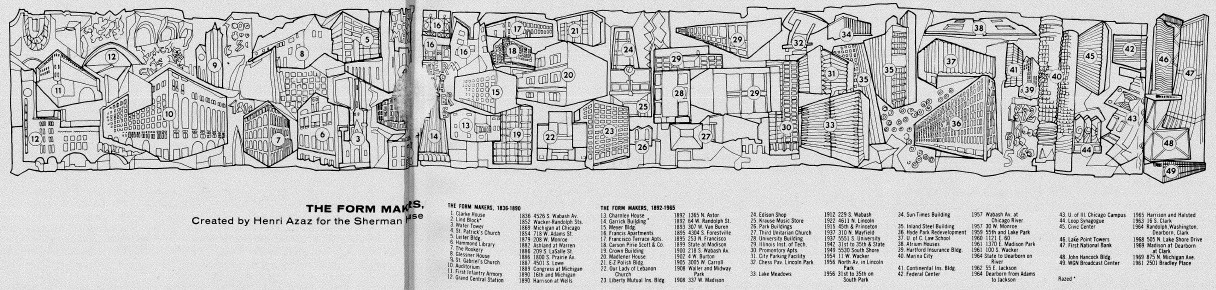

More forgotten history: In 1969, an enormous 10 by 57 foot concrete relief sculpture titled The Form Makers: 1836-1969 was unveiled in the lobby of the Sherman House Hotel, located on the block bounded by Lake, Clark, Randolph and LaSalle. Sculpted by Henri Azaz, who also completed the still-extant Hands of Peace at the entrance to the Chicago Loop Synagogue at 18 South Clark Street, this may have been the largest art piece to chronicle the history of Chicago buildings, and the Lind Block was the second building depicted in this sculpture. The cost of this sculpture in 1969 was $75,000, including a $30,000 fee to the artist;6 this total cost is the equivalent to $478,000 in 2014 dollars.7

Inland Architect, 1969

The Sherman House would close just four years later, in 1973. In 1976, this artwork was donated to Rosary College (now Dominican University) in River Forest, Illnois, and was reinstalled outdoors next to a parking lot.8 With construction of a new campus building, the piece was moved to a nearby location, with no plans for its reinstallation. Dominican University destroyed Azaz’s massive sculpture in the summer of 2008; the Director of Buildings and Grounds at the time, Dan Bulow, noted that “it was just like throwing away concrete.”9 The cost for disposing of Henri Azaz’s grand sculpture was $1,200.10

The institution entrusted with preserving The Form Makers had no regard for its preservation, and noted shortly after its destruction, “Maybe the wall’s time had truly come after all. Although many students and faculty at Dominican will fondly remember what became affectionately known as ‘The Wall’ with a certain nostalgic longing, perhaps the piece really does offer more in the way of growth as a simple memory than as a reality.”11

Top Left: Realty & Building, 1973 Remaining Photos: Patrick Steffes, October 2013

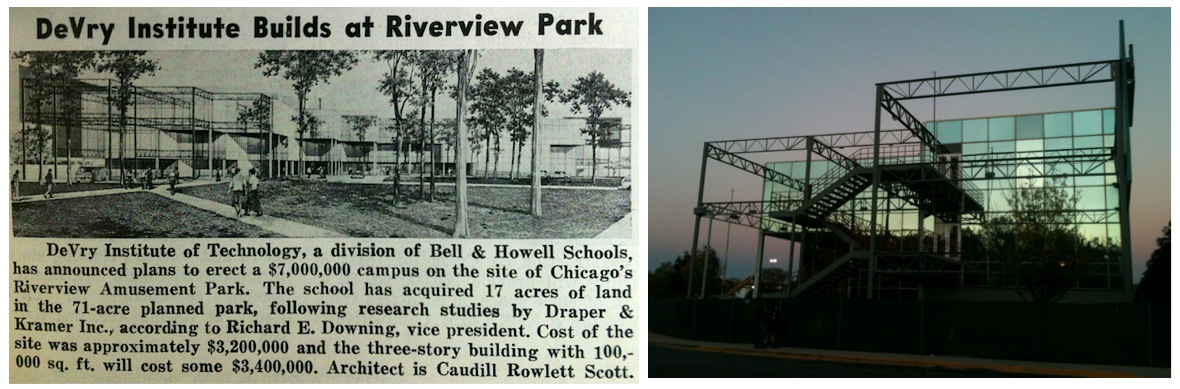

Another significant local project less than 40 years old to be demolished in recent years with little notice or attention was one of the best examples in Chicago of the high-tech architecture style. High-tech was at its peak in the 1970s and 1980s, and the building seen above was announced in 1973 for the DeVry Institute of Technology at the redevelopment site at the North Branch of the Chicago River, West Belmont and North Western Avenues. Designed by the noted educational building architecture firm of Claudill Rowlett Scott, the pictures above of the building during its demolition were taken in October 2013.

Planning the Region of Chicago

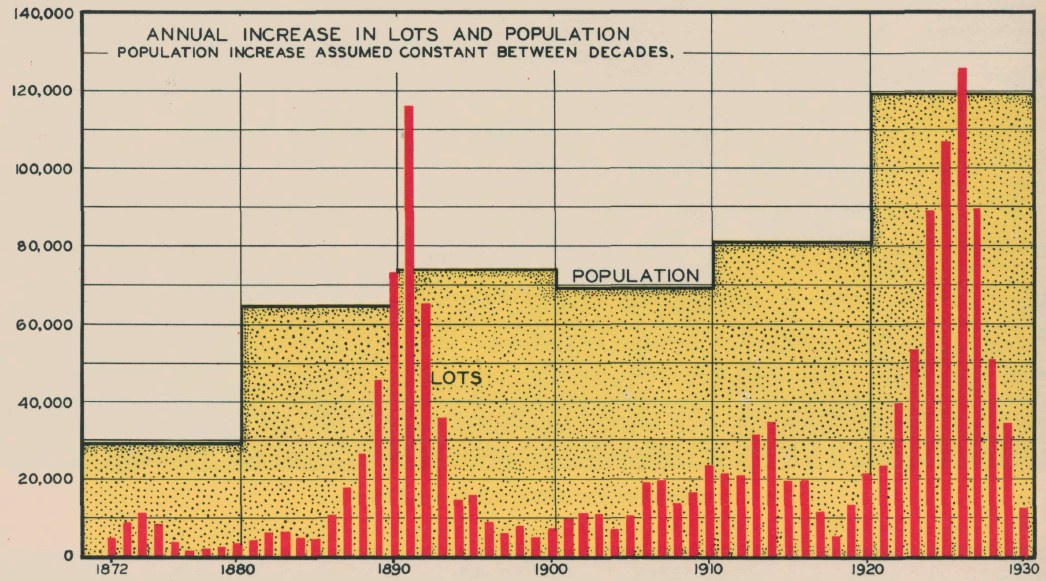

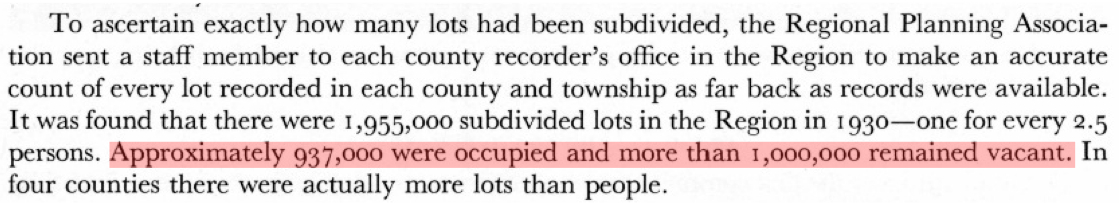

While the financial catastrophe of the Chicago area’s enormous housing bubble of the 2000s is still well-remembered, previous instances of Chicago’s vast overbuilding and rampant speculation are nearly completely forgotten in the historical narrative of Chicago. In the extraordinary 1956 book Planning the Region of Chicago published by the Chicago Regional Planning Commission, past overbuilding and excess plotting of building lots throughout the region is detailed in depth, including during the end of the nineteenth century and in the decade after the end of World War I, as seen in the chart above.

Planning the Region of Chicago

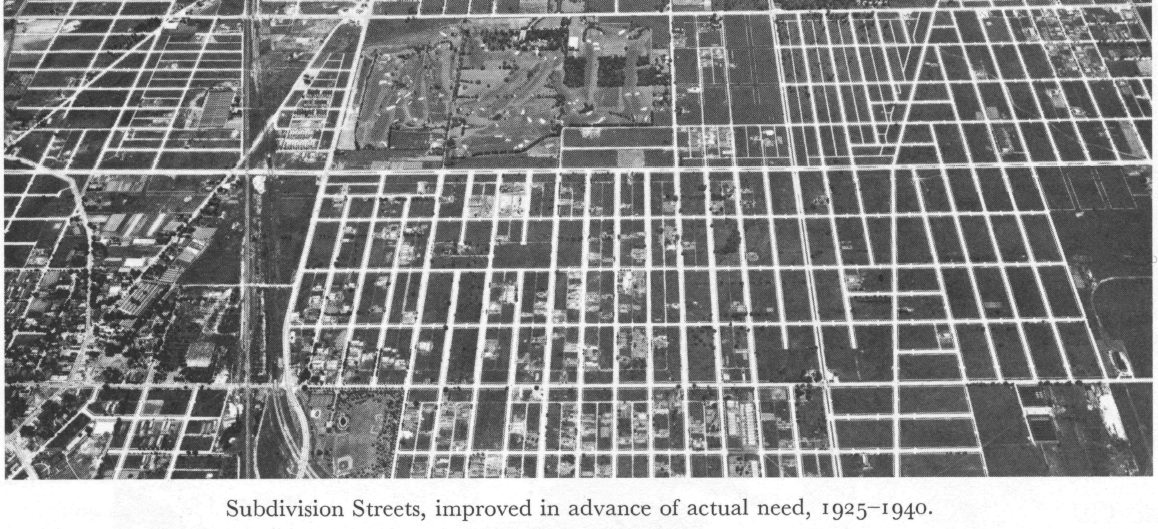

The immense scale of speculative subdivisions in the Chicago area in the 1920s in general, and Skokie in particular, can clearly be seen in the undated aerial photo seen above. Skokie was notoriously plagued with improved streets and tens of thousands of vacant lots; according to a 1954 University of Chicago research paper, in 1948, some 22 years after the peak year for the development of residential lots in the region, it was estimated that the Village of Skokie alone had 30,000 vacant lots, and that 18,000 of these lots had been vacant for at least 10 years.12 Additionally, it was noted that as of September 30, 1948 there were no fewer than 381 completely vacant blocks in Skokie. 13

Residential overbuilding was one of the many causes of the Great Depression, and Skokie’s little-known role in the Chicago area’s housing bubble of the 1920s was discussed during our September 2013 Corporate Kings North Bus Tour. A visitor to Skokie today can easily spot many instances of incongruous multi-story 1920s apartment buildings next to modest postwar ranch houses, built decades later.

Planning the Region of Chicago

As described above, of the nearly two million subdivided lots completed in the Chicago area, more than half were vacant in 1930. Residential construction virtually ground to a halt in the Great Depression; while 5,762 single family homes were completed in the City of Chicago in 1927, single-family homes completed would plunge 96.9% to just 180 homes in 1932.14

Chicago apartment building fell even more drastically – a 99.9% drop from 36,875 apartment units completed in 1927 to just 42 apartment units completed five years later.15 It would take decades for a renewed demand in housing, notably following the end of World War II, for vacant lots in Chicago and throughout the region to finally be developed.

Top: Patrick Steffes, May 2014 Bottom: Apple Maps, no date

A 1920s subdivision that was partially built and ultimately abandoned is now a part of the Wolf Road Prairie Nature Preserve in west suburban Westchester, northwest of the intersection of Wolf Road and West 31st Street. Well-used by local residents, former curb cuts, sidewalks, a light pole (top left) and outlines of proposed streets can easily be seen. This preserve contains a remarkable array of plants and wildlife, as described here.

Apple Maps, no date

Eighty years after Chicago’s epic subdivision boom and bust of the 1920s, history repeated itself throughout the region with a vengeance in the early years of the twenty-first century. These new housing developments were often located in far-flung locations, such as in Hampshire, Illinois, a village of fewer than 6,000 people in Kane County, approximately 60 miles from the Loop.

One of these ill-fated subdivisions in Hampshire was Tuscany Woods, seen above. Although the builder of Tuscany Woods, Pasquinelli Homes, had reported $580 million in revenue at the peak of the most recent housing bubble in 2006, the company would be liquidated in federal bankruptcy court starting in April 2011. 16

Internet Archive Wayback Machine, February 2006

An even more ambitious “new urbanist” development has been in the planning stages for more than 15 years, as reported in a 2009 article in a local newspaper. Located about 45 miles from the Chicago Loop in Chesterton, Indiana, Coffee Creek Center was a vast planned development of more than 600 acres at the Indiana Toll Road and Calumet Road.

Top: Apple Maps, no date Bottom: Patrick Steffes, May 2014

After sitting mostly undeveloped for years, a corporate headquarters and laboratory is being built in a portion of Coffee Creek Center, as reported here. The empty streets, alleys, and sidewalks of much of Coffee Creek remain, as of this writing, a contemporary remnant of the long history of vast of overbuilding in the Chicago area.

Top: Serhii Chrucky, November 2013 Bottom: Apple Maps, no date

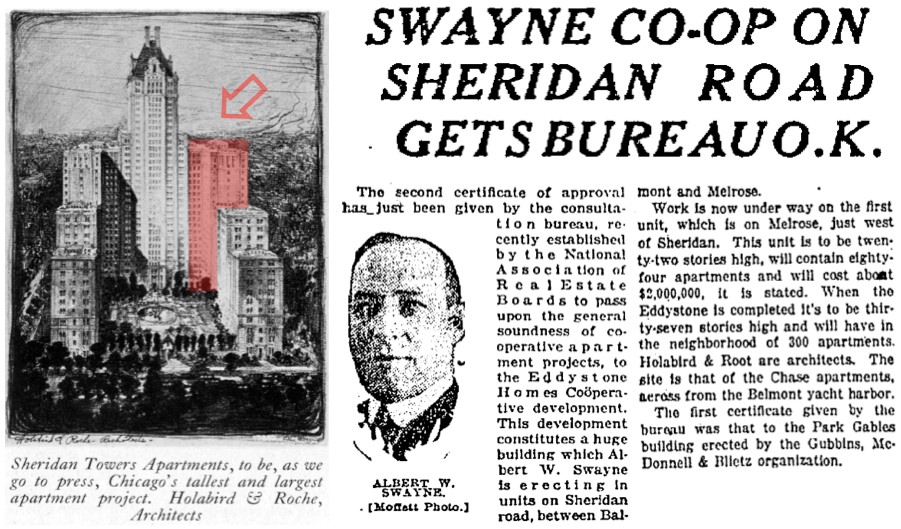

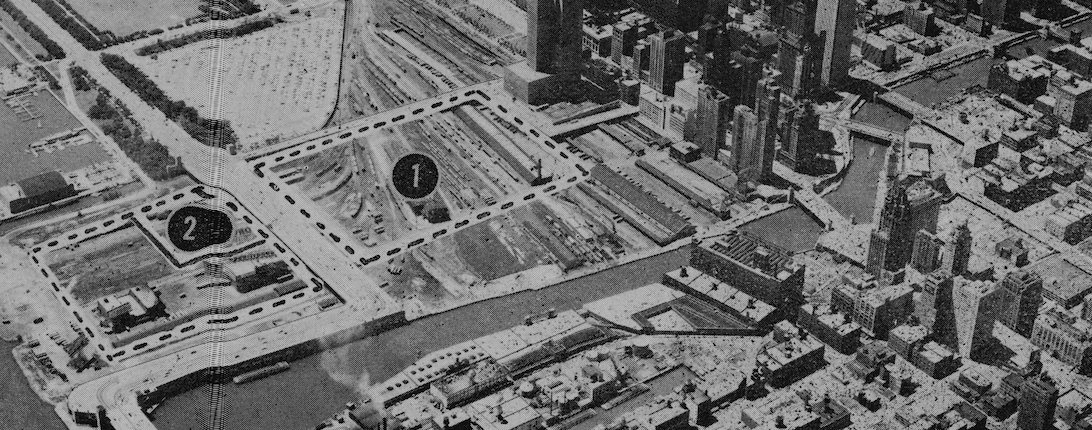

Left: Architecture, 1928 Right: Chicago Tribune, 1928

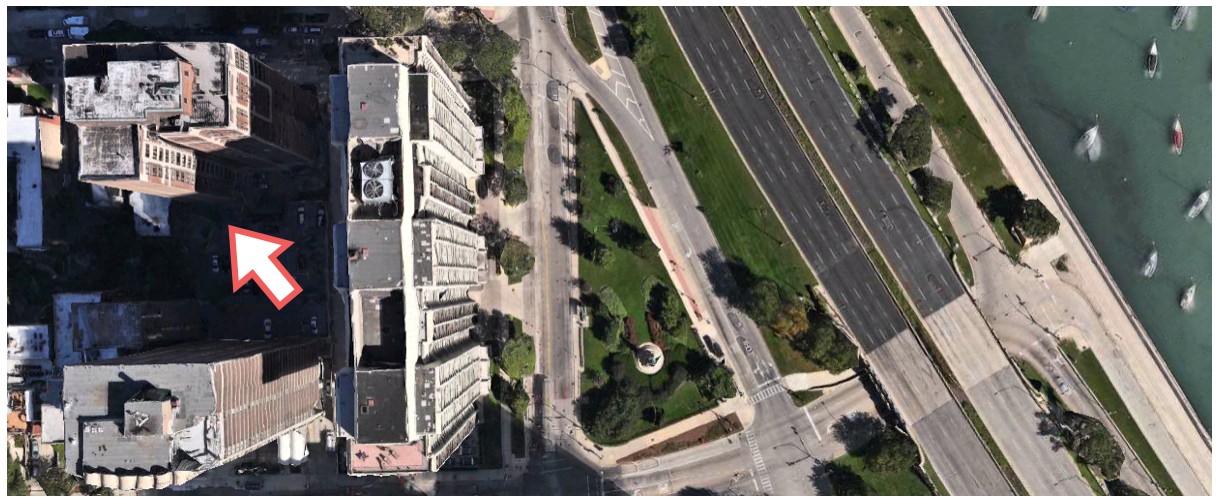

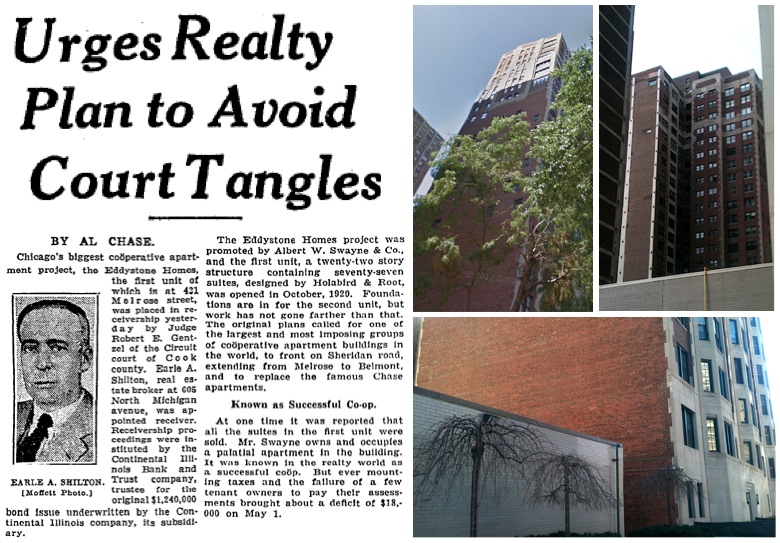

Another prominent remnant in 2014 of the Chicago region’s 1920s housing crash is a now a condominium building still known as The Eddystone at 521 West Melrose Street in Lake View, with its location highlighted in pink above and below. Designed by Holabird & Roche as the first section of what was also known as the Sheridan Towers cooperative apartment project, The Eddystone had the unfortunate opening date of October 1929, the same month as the great stock market crash. The remainder of Sheridan Towers / The Eddystone illustrated above would never be built.

Top: Apple maps aerial, no date Bottom Left: Chicago Tribune, 1932 Bottom Right Center and Bottom: Google Street View, no date Right Center: Patrick Steffes, March 2014

The small completed section of what had been promised at the time as the largest and tallest Chicago apartment building ever built is seen above lower right. An examination of The Eddystone reveals it was indeed planned to be a part of a much larger project, most notably its largely windowless walls facing prime skyline and Lake Michigan views where the rest of this apartment building was planned to connect to the Sheridan Towers project. Another building on the planned site of Sheridan Towers would not be built until decades after the completion of this odd and enduring relic of the Great Depression, as described below.

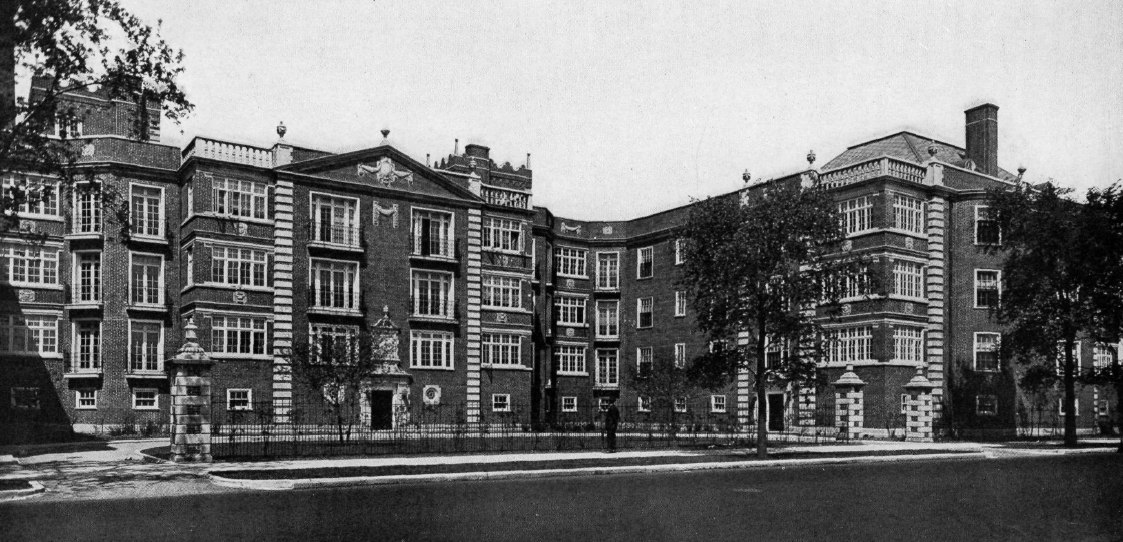

The American Architect, 1916

The American Architect, 1916

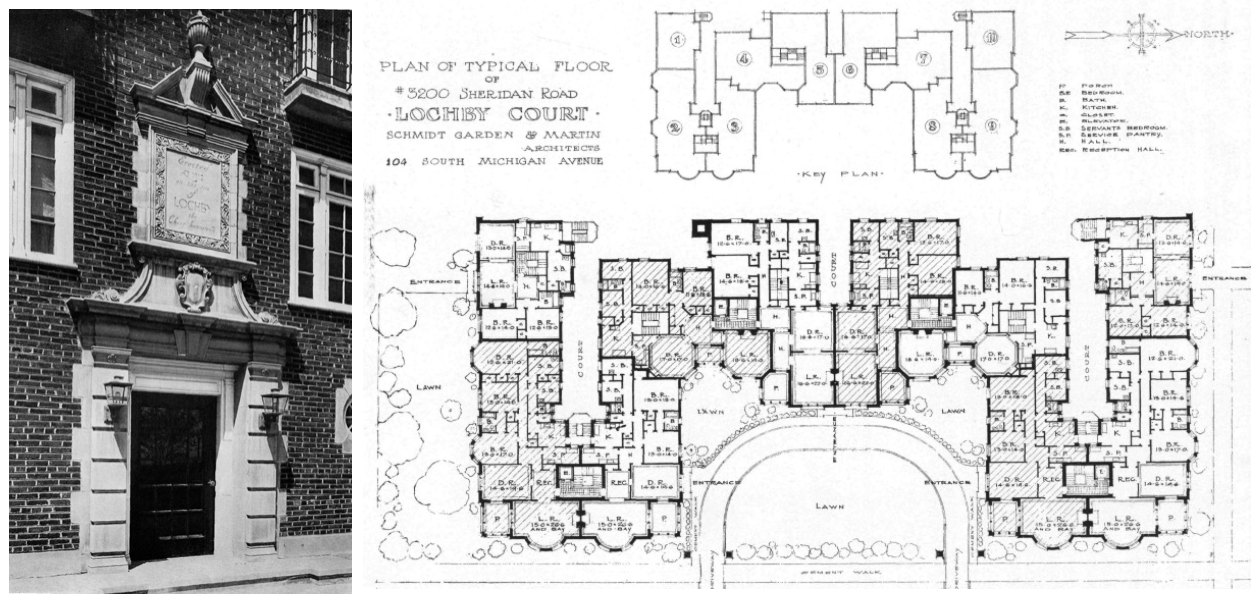

Designed by the prolific local firm of Schmidt, Garden & Martin, Lochby Court was one of the first of Chicago’s large luxury lakefront apartment buildings. Completed before World War I (the tablet seen above left gives the date of 1912), this lavish building was also once home to Chicago’s most recent Republican mayor, the notoriously corrupt William Hale “Big Bill” Thompson, as noted in a 1965 article, below left.

Left: Chicago Tribune, 1963 Right: Peoples Gas ad in Inland Architect, 1966

Lochby Court would remain standing for another 25 years after the spectacular failure of most of the Sheridan Towers project and the construction of the building that stands on this site today, Hausner & Macsai’s often-overlooked Harbor House. The design of Harbor House is typical of the great skill Hausner & Macsai used on their residential and hotel projects, including the much-lamented former Hyatt House in Lincolnwood (aka The Purple Hotel), examined during its demolition by Forgotten Chicago during a bus tour in September 2013.

Chicago Tribune, May 1929

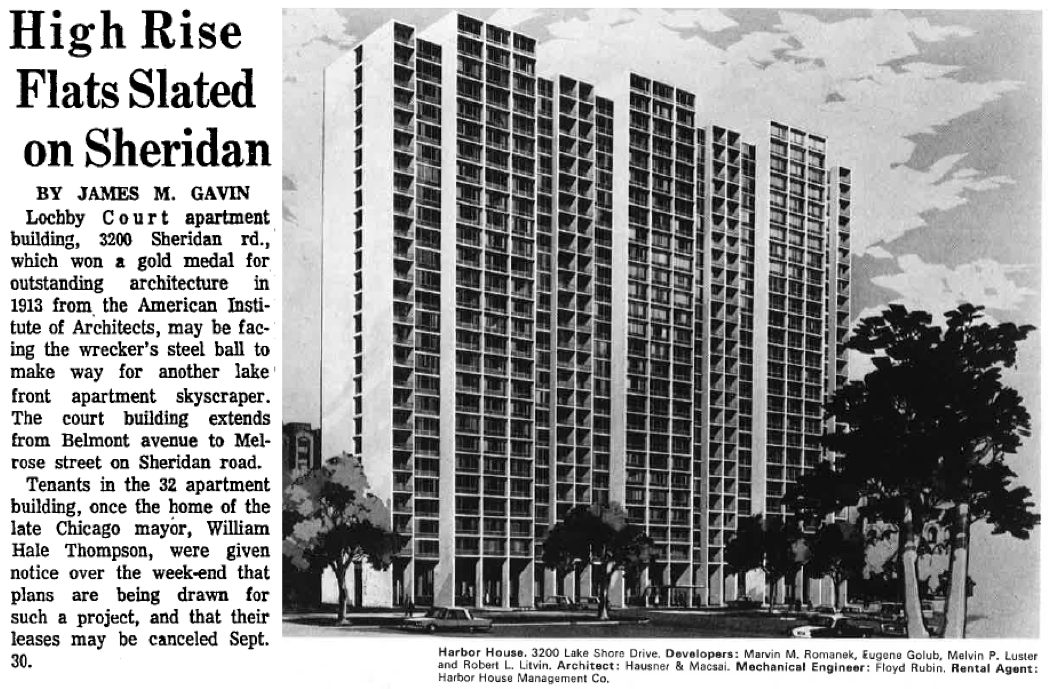

The most audacious of Chicago’s many unbuilt projects of 1920s was the Crane Tower by Walter W. Ahlschlager, announced in May 1929 as the world’s tallest building.17 Designed to be the first structure built over the air rights of the Illinois Central Railroad, north of the planned extension of Randolph Street east of Michigan Avenue, the Crane Tower did not make it past the rendering stage.

Realty & Building, 1962

The image above was published in 1962, and shows the site of the first residential project in Illinois Center, the Outer Drive East apartments, indicated as “2” above. In 2014, decades after the Crane Tower and neighboring buildings were first announced, large undeveloped lots still remain within Illinois Center.

ChicaoPast, 1972

The Outer Drive East apartment project is seen in lonely isolation above in 1972, fully 43 years after grand plans for Illinois Center were first publicized. While perhaps no other area of Chicago has a more desirable location as the meeting point of Lake Michigan and the Chicago River, the 85 years-and-counting development of Illinois Center may hold the record as the slowest-realized neighborhood development to be completed in Chicago history.

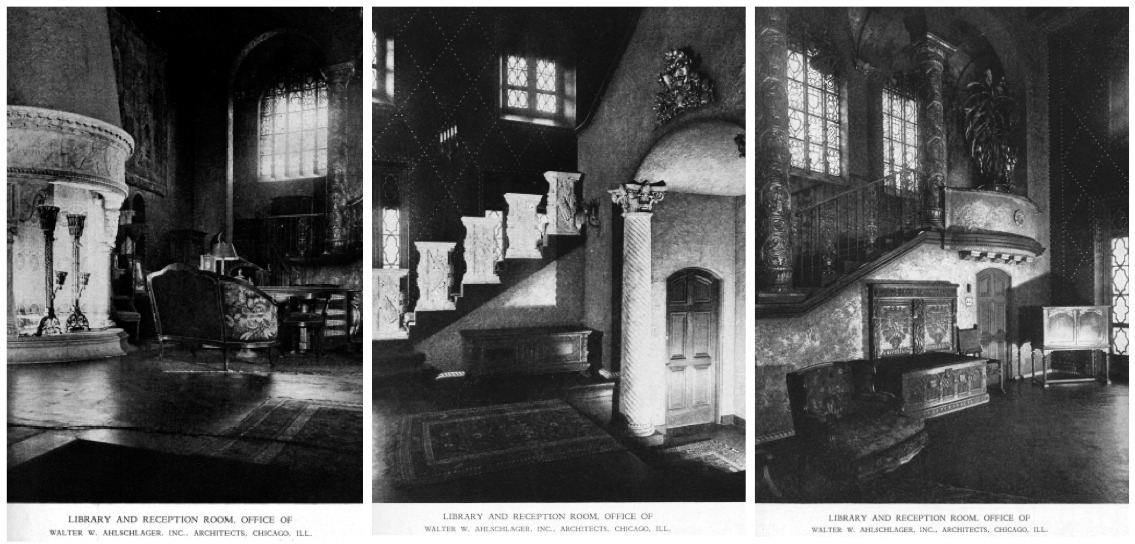

The American Architect, 1926

Walter W. Ahlschlager, the architect of the Crane Tower, is often noted during Forgotten Chicago tours and presentations. Ahlschlager would design some of nation’s grandest buildings, including the Medinah Athletic Club (now Hotel Inter-Continental Chicago) and the Carew Tower in Cincinnati. Befitting his firm’s many commissions in the 1920s are views of Alschlager’s lavish office seen above at 65 East Huron, published in 1926. Long demolished, these pictures of his opulent office are not known to have been republished in nearly ninety years.

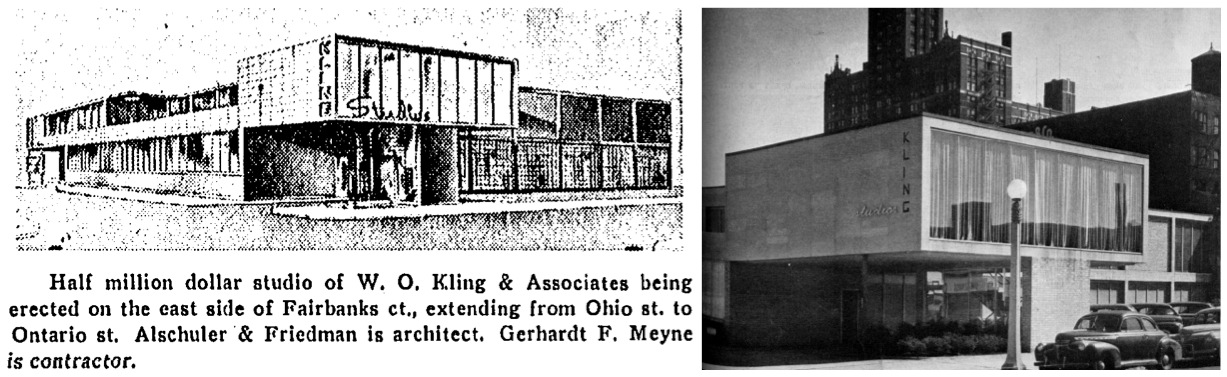

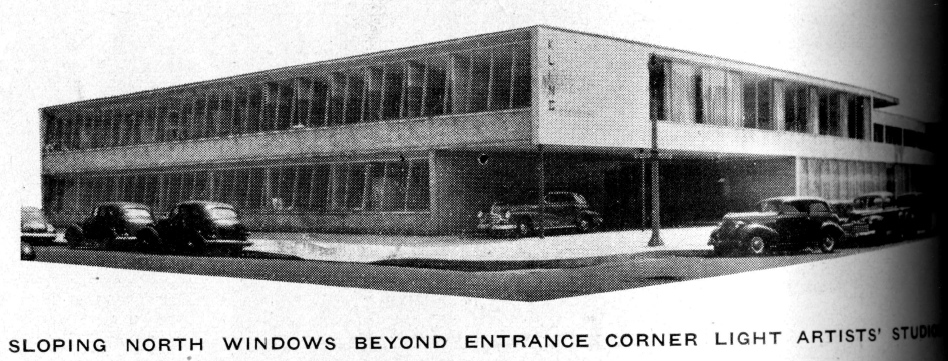

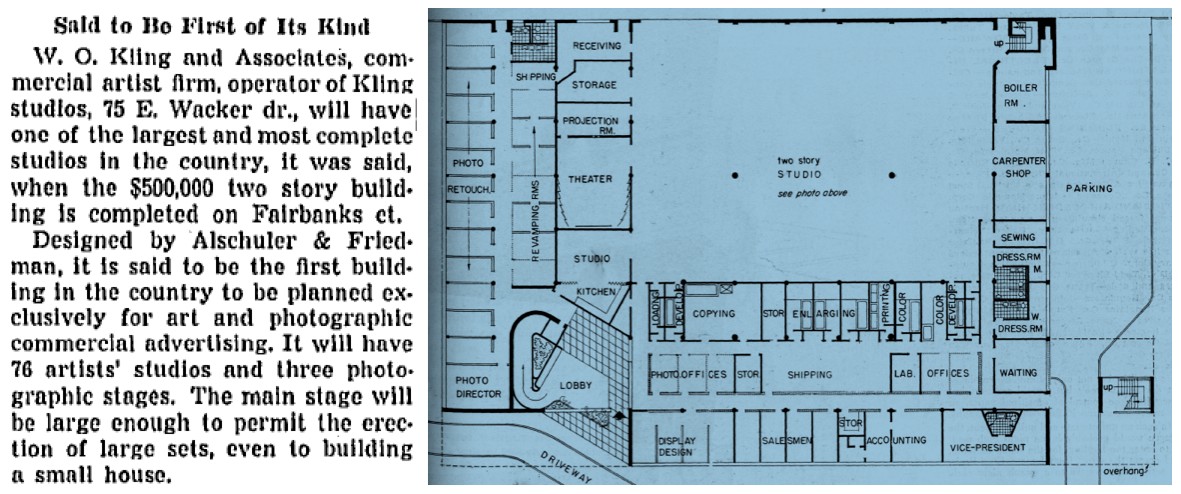

Top Left: Chicago Tribune, 1945 Remaining Photos: Architectural Forum, 1947

The architectural firm of Friedman, Alschuler & Sincere is one of the least-studied and most overlooked of the many modernist firms to make a significant contribution to the the Chicago area’s built environment. One of our favorite vanished buildings by this prolific firm was the ultra-modern Kling Studios building in Streeterville, seen above, and published in Architectural Forum in 1947.

Left: Architectural Forum, 1945 Right: Architectural Forum, 1947

Despite W. O. Kling’s national prominence at the time, the later story of Kling Studios seems to be lost to history. No further information has been found about this firm; the site of this building in 2014 is a large hotel complex completed in the 1970s.

Top and Bottom Left: Architectural Forum, 1954 Bottom Right: Patrick Steffes, March 2014

One of Forgotten Chicago’s oddest and tiniest recent research finds is a four-classroom school in Schaumburg. seen above. Still extant and rediscovered in 2014, complete with “bumpety stone,” this was built as the Village of Schaumburg’s first elementary school and opened in 1954.19 Now used as part of the school district’s administration complex, this modest commission was designed by architects Paul Schweikher and Winston Elting. Schweikher (1903-1997) designed several notable buildings in the Chicago area, including the landmark Third Unitarian Church in Austin and Schweikher’s own home, also in Schaumburg, which offers tours.

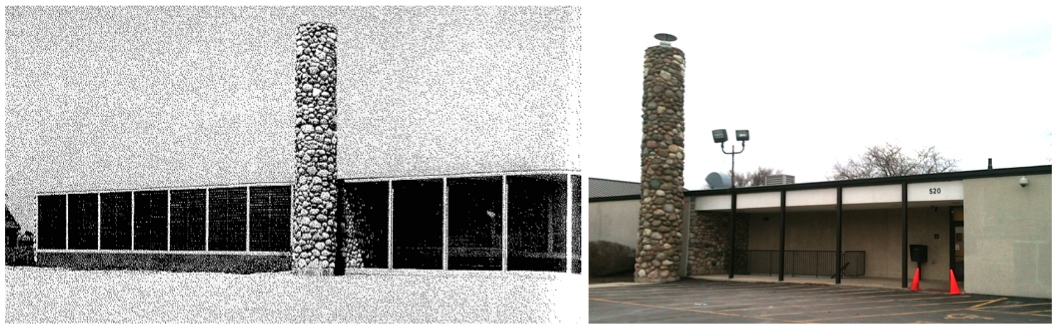

Left: Realty & Building, 1955 Right: Chain Store Age, 1957

Forgotten Chicago has long been researching and sharing information about the overlooked retailers and shopping centers throughout the region, notably structures that are at least partially extant. One of the most overlooked of these is the Scottsdale Shopping Center designed by Sidney H. Morris Associates seen above, and still partially remaining in 2014 at South Cicero and West 79th Street.

Scottsdale had a bizarre and dramatic opening on November 17, 195520 that included the release of radioactive smoke, for reasons unknown. The Scottsdale sign featured a distinctive tartan plaid design; one of the main tenants at Scottsdale was Goldblatt Bros.

Architectural Forum, 1953

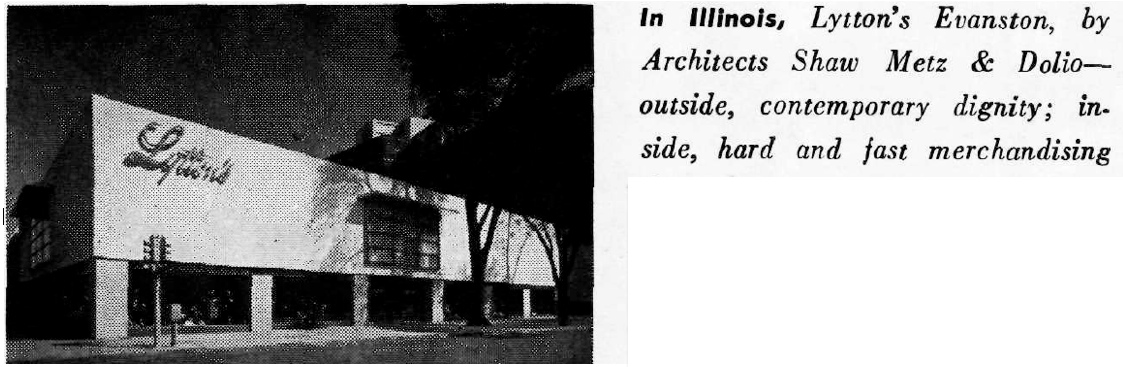

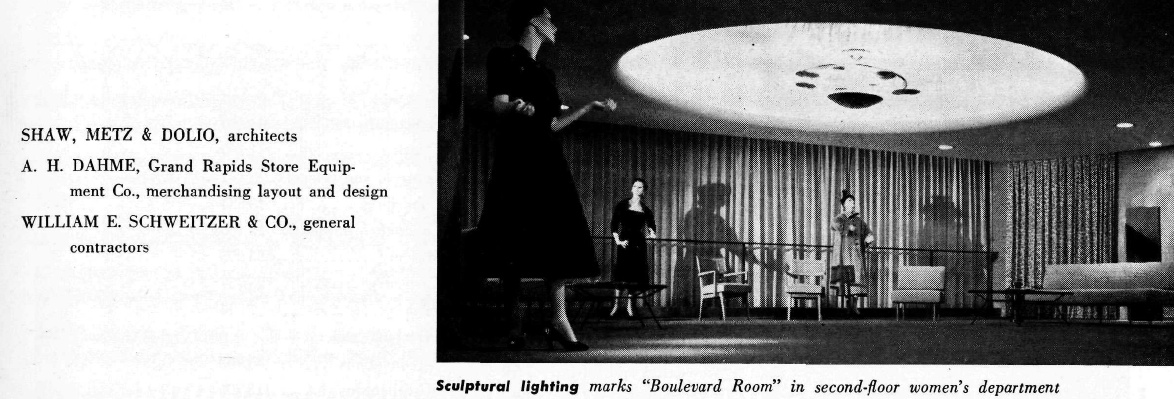

Other retail relics that will likely never make it into architecture or history guides are also shared during tours and presentations. During our August 2013 tour of Evanston, we examined the former Lytton’s by Shaw, Metz & Dolio, above, sharing these along with other rarely-seen interior images and floor plans. This former Lytton’s building still stands in downtown Evanston, and its 1950 cornerstone was noticed for the first time by Forgotten Chicago during this tour.

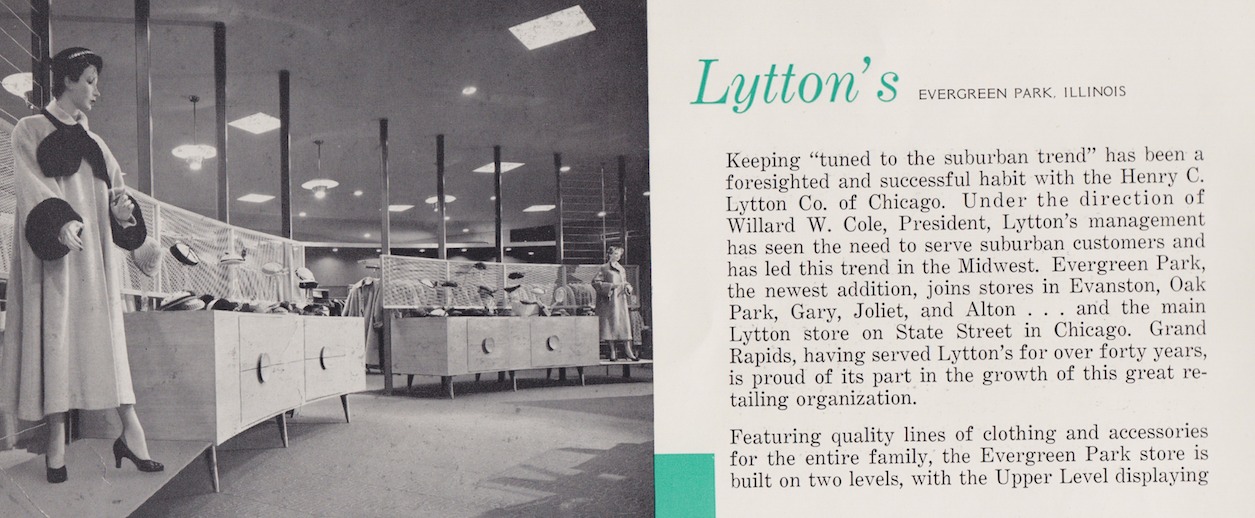

Top: Forgotten Chicago Archives Bottom: Realty & Building, 1952

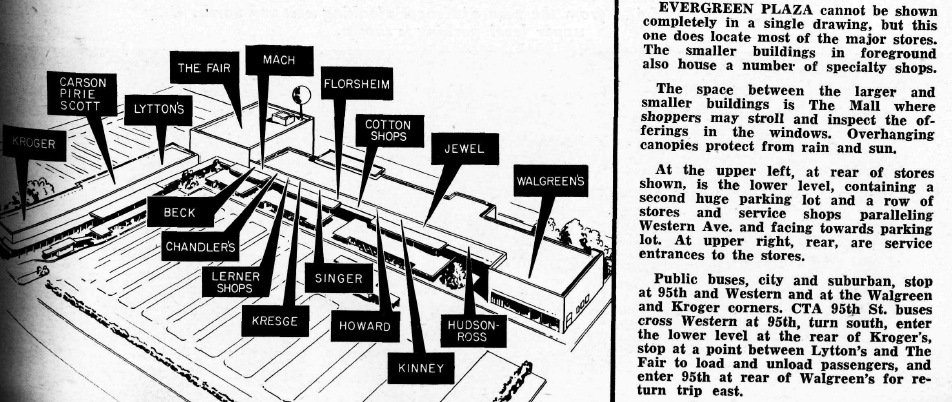

Another building housing a former Lytton’s store still standing (as of this writing) was their 1952 location at Evergreen Plaza in Evergreen Park by Holabird & Root & Burgee. Forgotten Chicago has been extensively documenting Evergreen Plaza, the first regional shopping center in the Chicago area and briefly the largest mall in the Midwest, since it closed in May 2013.

JaNae Contag

A top-to-bottom video tour of how Evergreen Plaza appeared on August 12, 2013 may be seen here, courtesy of Forgotten Chicago Contributor JaNae Contag. As of this writing, only a Carson Pirie Scott and Planet Fitness remain open at opposite ends of Evergreen Plaza, with the remainder of the mall closed and abandoned, its future in doubt.

Forgotten Chicago Archives

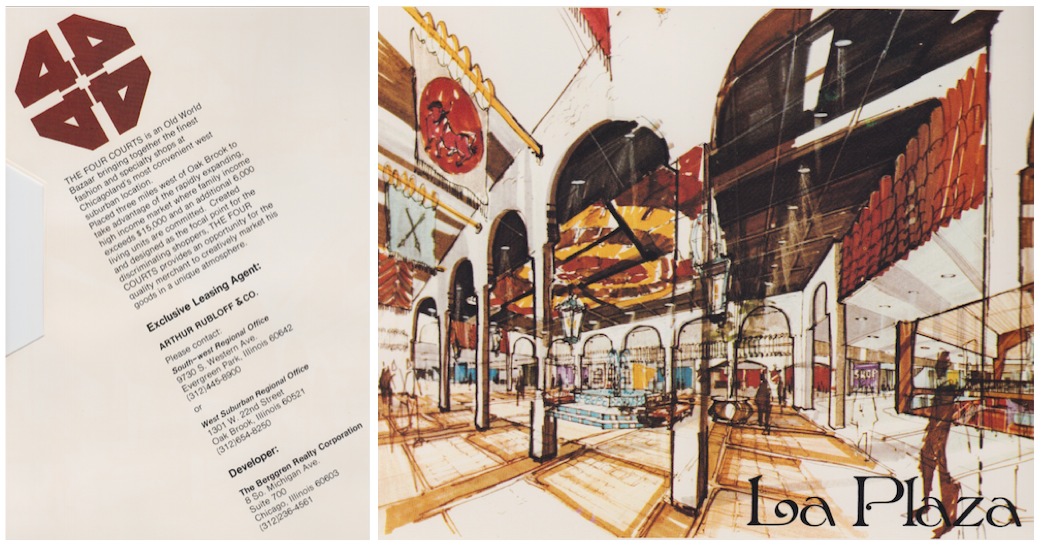

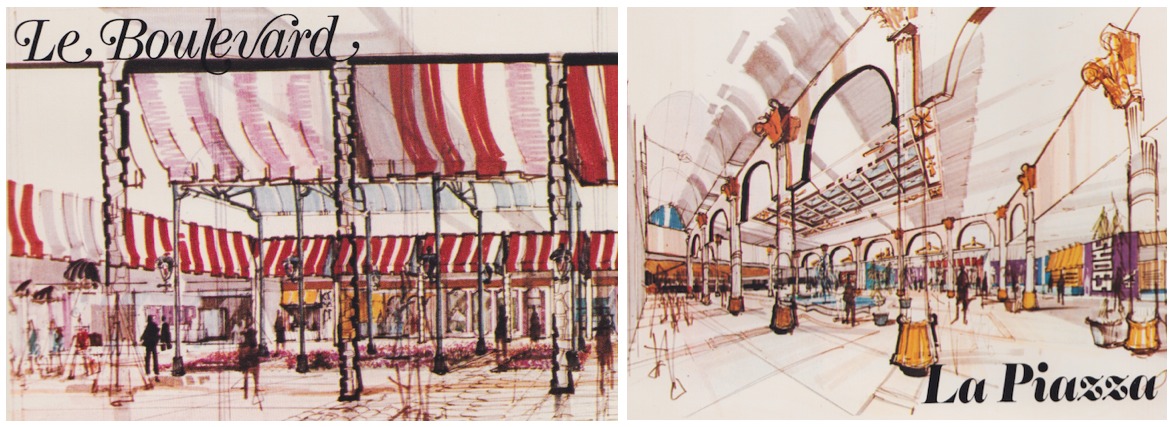

One of Forgotten Chicago’s favorite recent finds was learning about The Four Courts, a highly ethnic indoor shopping mall announced in November 1973 for west suburban Downers Grove.21 Designed by Philip M. LeBoy, this mall was to have been built around “courts” representing four popular European countries – La Piazza (Italy), Le Boulevard (France), La Plaza (Spain) and The Courtyard (Great Britain, not shown above).

Unfortunately for lovers of period retail, The Four Courts never made it past the brochure stage. Just one building planned for this large development was constructed22 – what is now the Rockwood Tap House at 3131 Finley Road; this building has since been heavily altered.

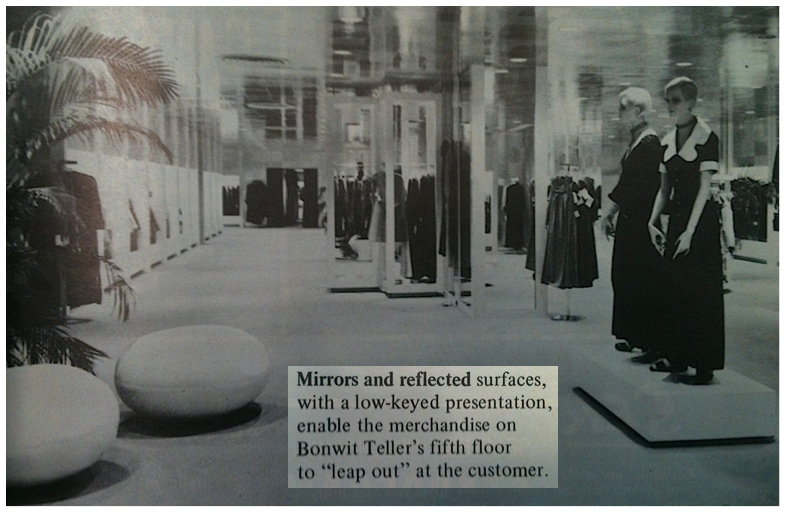

Top: Chain Store Age, 1971 Bottom: Patrick Steffes, January 2014

What is now the fifth floor of the John Hancock Center parking garage has a glamorous past. As described in detail here, New York specialty store Bonwit Teller moved from their 1949 location at 830 North Michigan to the recently opened Hancock Center just up the street in 1971. Following the bankruptcy of the Bonwit Teller chain and the closing of this store in 1990, the owners of the Hancock Center converted the fourth and fifth floors of the former luxury retail space into additional parking. A close inspection by the Forgotten Chicago research team found no evidence of plush carpeting, mirrored ceilings, or egg-shaped ottomans on the fifth floor of the parking garage seen above, as it appears in 2014.

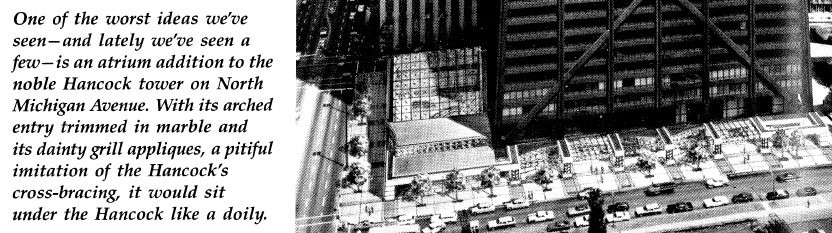

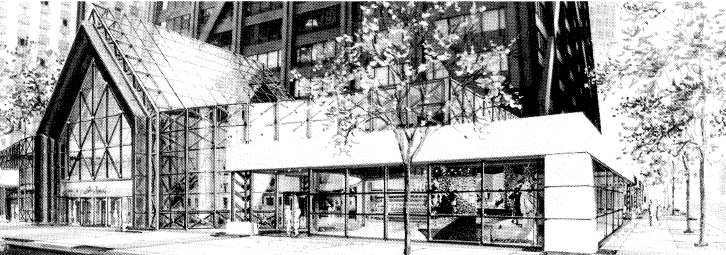

Inland Architect, 1988

Even before the closing of the Hancock Center’s multi-story Bonwit Teller store in 1990, the building’s owners faced a competitive retail environment including the vast 1988 shopping mall at 900 North Michigan, and the since-closed Chicago Place vertical mall, a 1990 complex built on the site of the site of the 1930s Zenith showroom. In 1988, the Hancock Center’s owners presented a plan shown above to tack on more retail space to the base of the building, which was unbuilt.

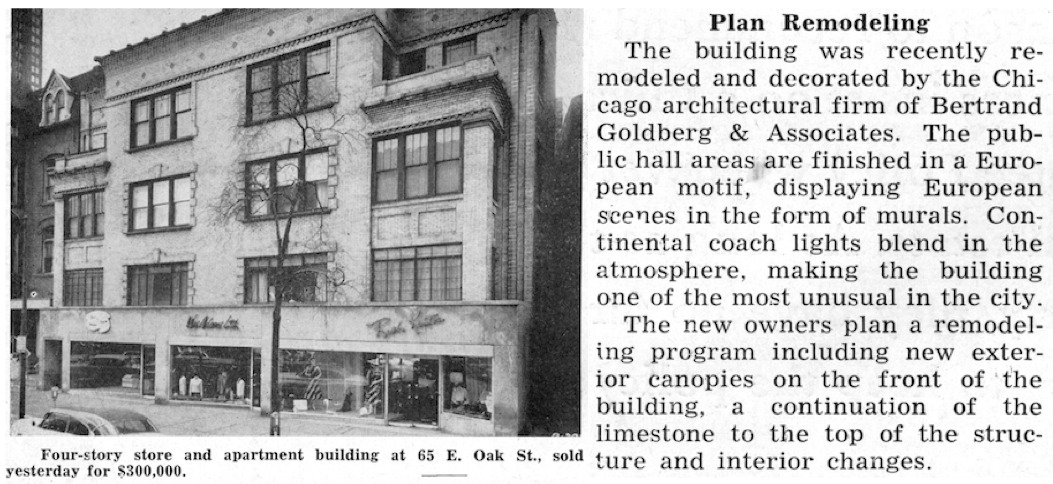

Realty & Building, 1955

A few blocks from the former Bonwit Teller and the John Hancock Center is a previously unknown commission by Bertrand Goldberg & Associates, discovered by Forgotten Chicago in 2013. Completed one year before Goldberg’s nearly intact and now-endangered Walton Gardens project, this remodeling was noted for its European murals and “continental coach lights” as described above. It is not known if any portions of this remodeling survive. For more information about the upcoming threat to Goldberg’s Walton Gardens at the northeast corner of North Rush and East Walton, visit the in-depth article by Lynn Becker here.

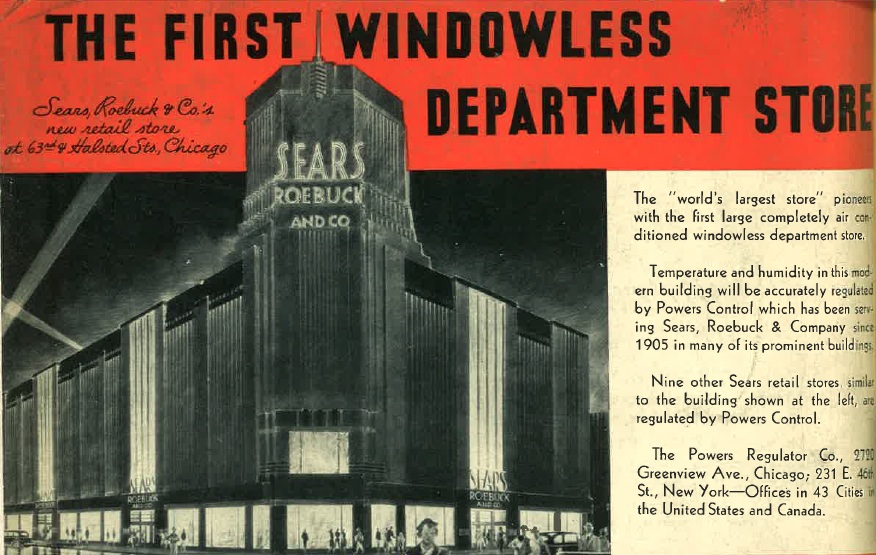

Architectural Forum, 1935

Forgotten Chicago is collaborating with The Chicago Art Deco Society to add overlooked or previously unknown projects to their extensive survey, forthcoming book, and museum exhibit on Art Deco in the Chicago area. One of the most overlooked of these buildings was the former Sears store in Englewood, shown above. The centerpiece of what was at the time purportedly the nation’s largest outlying shopping district, the mammoth Sears above opened in 1934 and closed in the 1970s.

Architecture, 1935

Following the repeal of prohibition in December 1933, many of Chicago’s hotels were quick to remodel public areas into up-to-the-minute spaces devoted to the consumption of alcohol. Chicago’s Morrison Hotel did so by 1935 as seen above, in a whimsical design by Holabird & Root, featuring an appropriate quote by Don Quixote, above. Another Loop hotel, the LaSalle, also featured a new cocktail lounge by architect James F. Eppenstein, which would end very badly in the following decade.

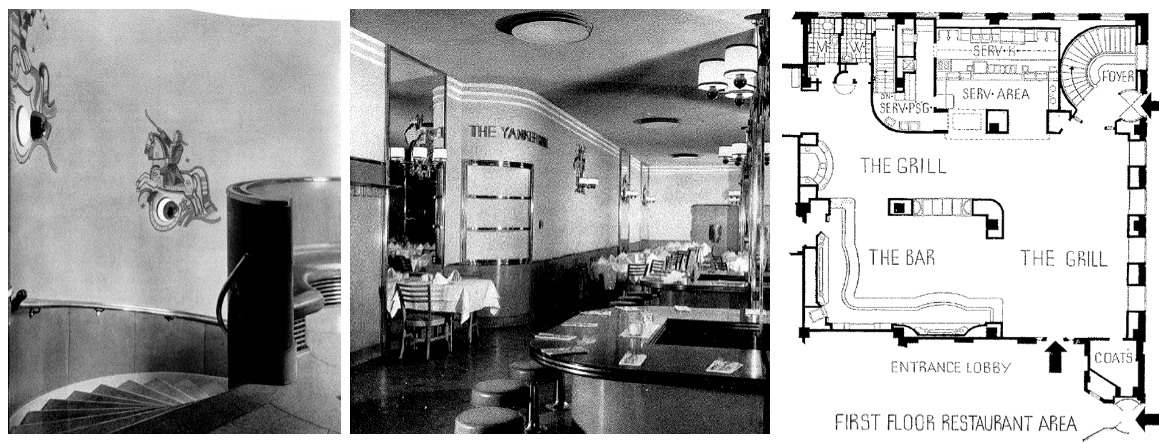

Architectural Forum, 1935

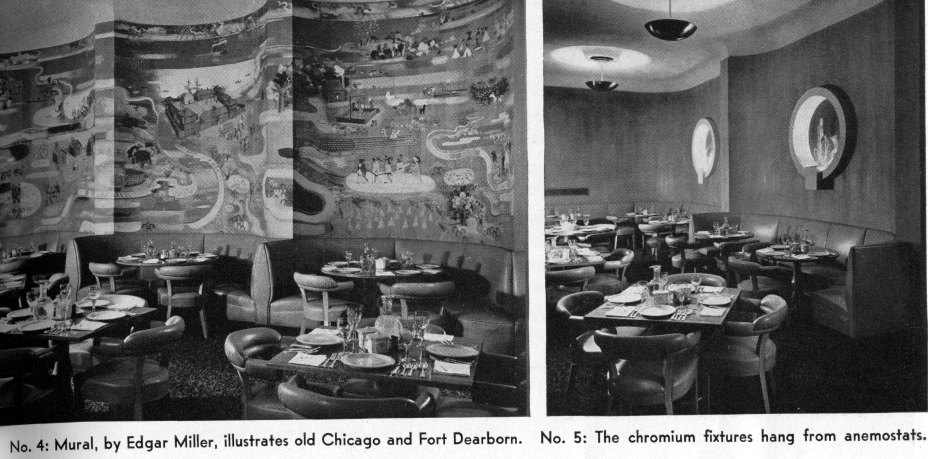

Another previously unknown commission was recently rediscovered by Forgotten Chicago: The Yankee Grill by Alfred Shaw, then of Graham, Anderson, Probst & White, and also featuring a mural by Chicago artist Edgar Miller. Located on the first and basement level of the Field Building at 135 South LaSalle, this enormous 600-seat restaurant had a patriotic red, white and blue theme down to the costumes worn by the restaurant’s waitresses.23

The also previously unknown Edgar Miller commission, seen above “provoked such gay notes as…Washington and Paul Revere.”24 Another notable feature of The Yankee Grill was a tank stocked with game fish from Wisconsin,25 with patrons using nets to catch the fish they wanted prepared for their meal.26

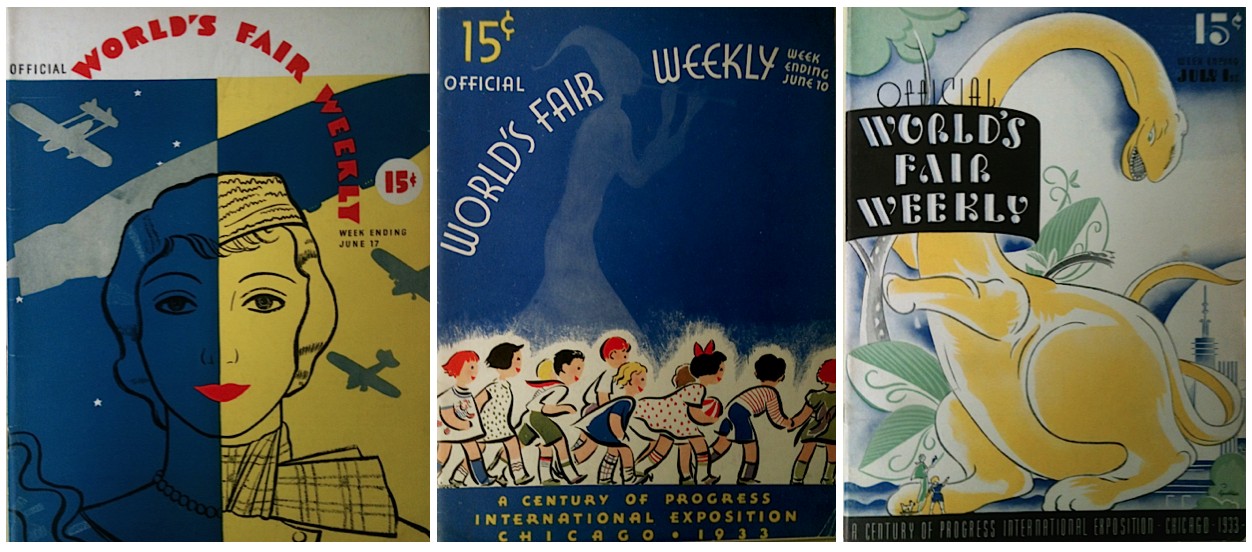

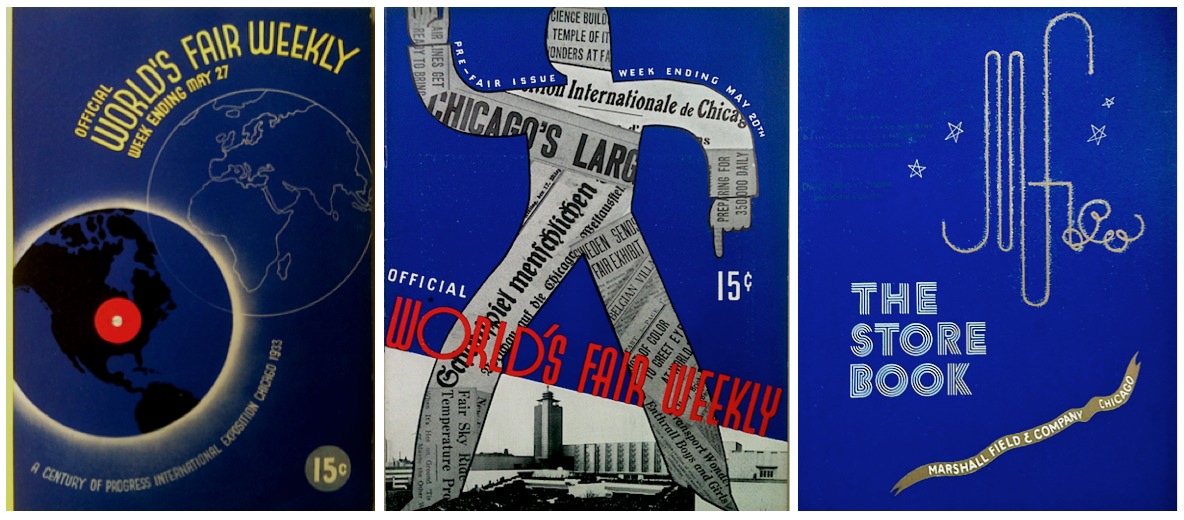

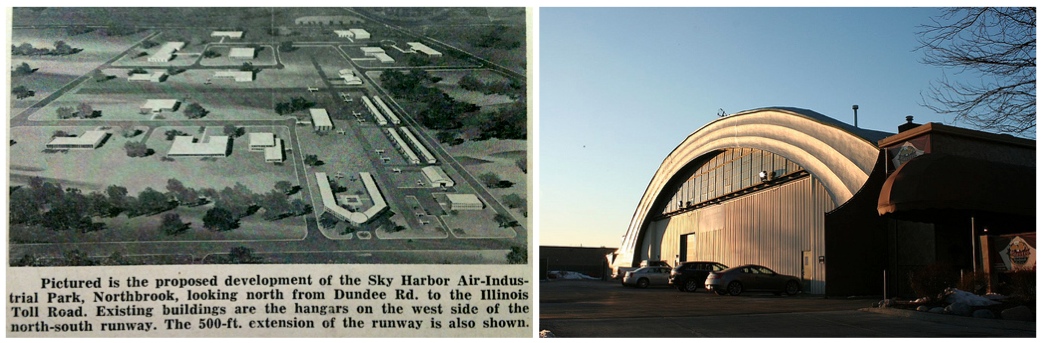

A Century of Progress records collection, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1933

Forgotten Chicago has examined the entire Century of Progress publications collection housed at the University of Illinois at Chicago, with a small sample of these seen above. These publications have been little-seen or republished in the past eighty years, and contain a fascinating history of how the Century of Progress and their exhibitors presented themselves to fair visitors, such as the modern graphics in the piece produced by Marshall Field & Company, above upper right.

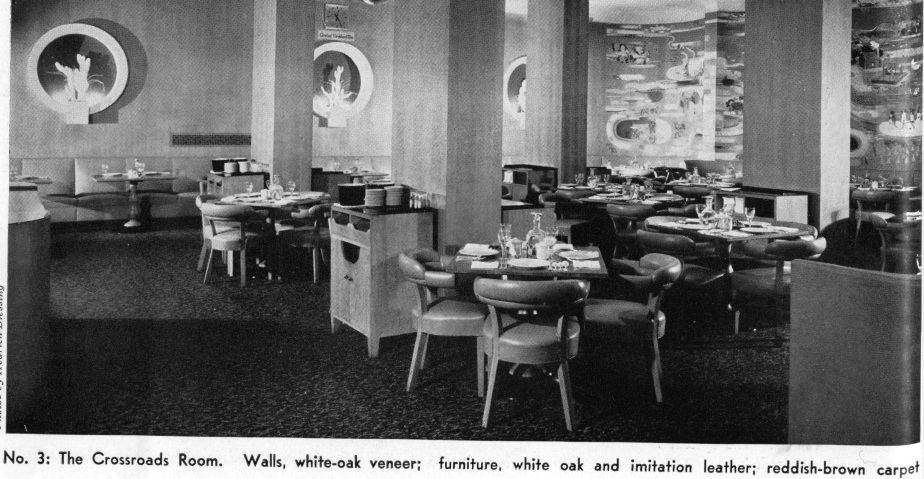

Architectural Record, 1940

Another mostly forgotten Art Deco landmark is seen above by noted Chicago architect and art collector Samuel Marx for the Fred Harvey Crossroads Restaurant at Dearborn Station. Perhaps best known locally for the original incarnation of the legendary Pump Room at the Ambassador East Hotel (now PUBLIC Chicago) in 1938, this Marx commission included a restaurant seating 102, a 50-seat cocktail lounge, and a 31-person lunchroom.27 Edgar Miller, Chicago’s great and recently rediscovered artist, was commissioned for the murals that commemorated both old Chicago and the southwestern routes served by the Santa Fe Railroad.

Architectural Forum, 1933

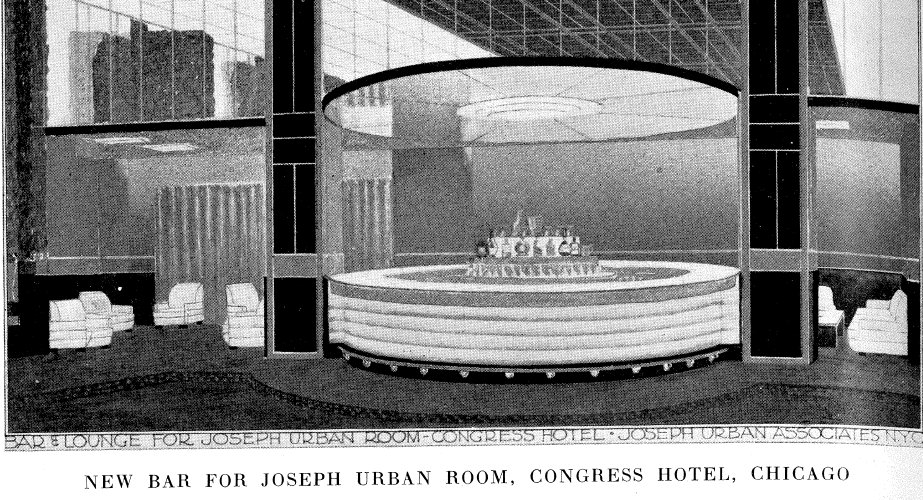

In our research of architectural magazines from the 1930s, no Chicago hotel received as much national press as the Congress Hotel on South Michigan Avenue. Opening in 1893, this hotel would have been due for a remodeling; one of these projects was designed by Joseph Urban (1872-1933), a New York City-based designer who was also Director of Color for the 1933-34 Century of Progress. The Joseph Urban Room seen above opened in the Congress in 1932.

Architectural Forum, 1937

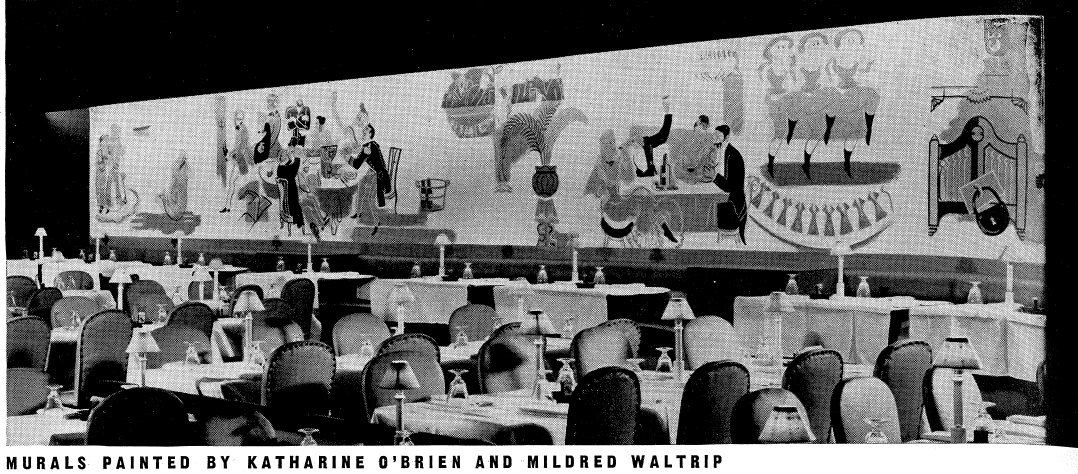

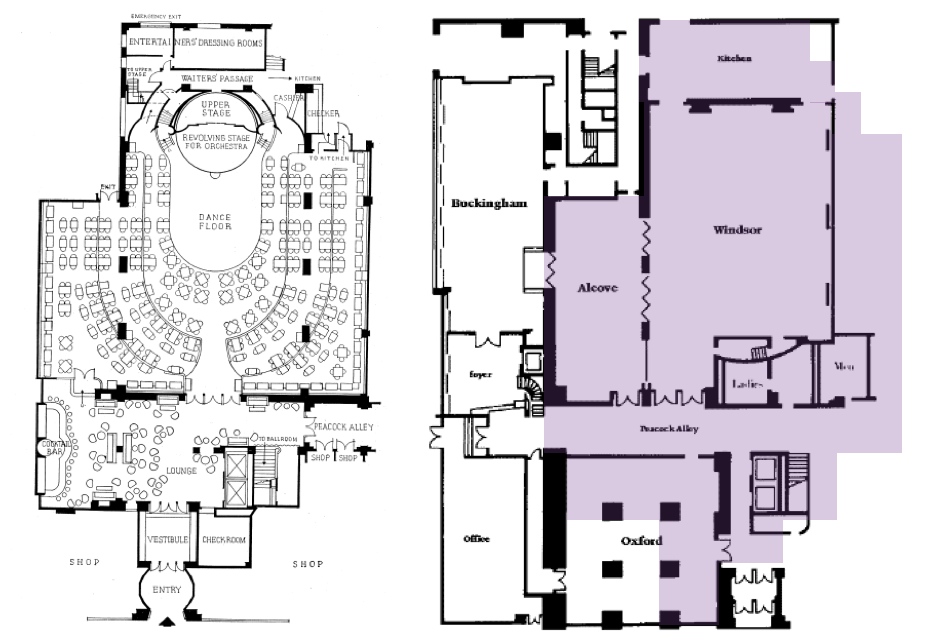

By 1937, the Congress would undergo another significant remodeling, this time by Holabird & Root, for their Casino night club, seen above and below. These photographs are unfortunately unavailable in color: in the corresponding article on the Casino, it is noted that “brilliantly colorful interior executed in crimson and fuchsia, with murals in shades of blue dubonnet, and magenta.”28 The Casino also featured a revolving stage, which “permitted the rapid alternation of two orchestras,”29 seen in the top photo.

Top Left: Congress Hotel Top Right: Architectural Forum, 1937 Bottom: Chicago History in Postcards, no date

The 1930s and current floor plan of the Congress Hotel is shown at top left. The later history of the Casino is less clear; in later years it became the Glass Hat Club, seen above in an undated postcard.

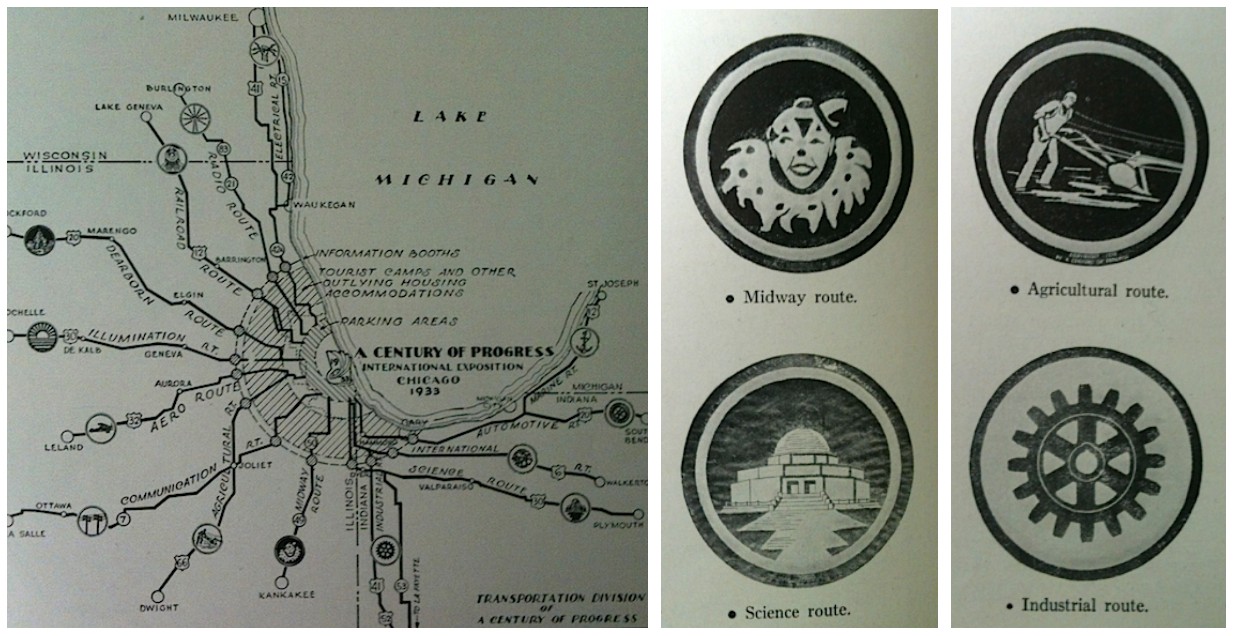

A Century of Progress records collection, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1933

One of our more interesting recent research finds was learning that highways in Illinois, Indiana and Wisconsin leading to the 1933-34 Century of Progress Exhibition were named with a series of fourteen identifying markers, four of which are seen above right. Although the Interstate Highway System and toll roads in Illinois and Indiana would be built decades later, by 1933 U.S. Highways spread throughout the region towards Chicago, and the organizers of the Century of Progress encouraged motorists to take these well-identified routes. It is not known if any of these markers or roadside information booths have survived 80 years after the Century of Progress.

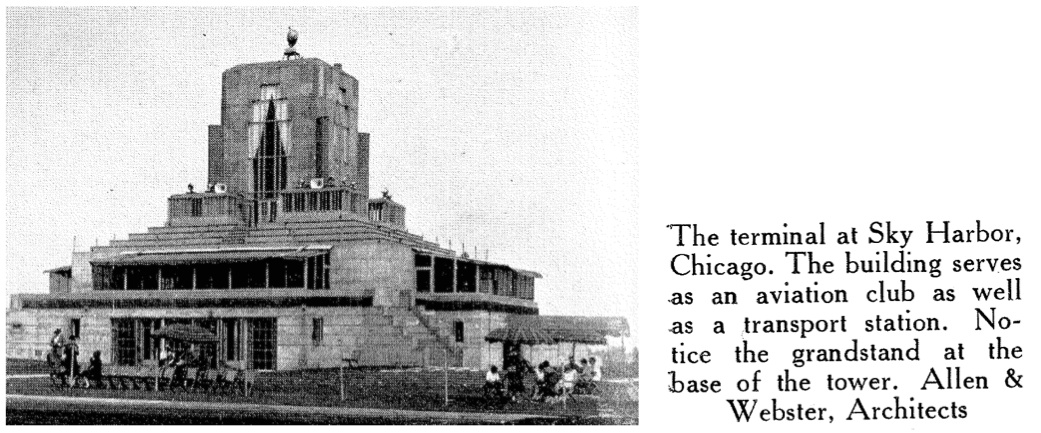

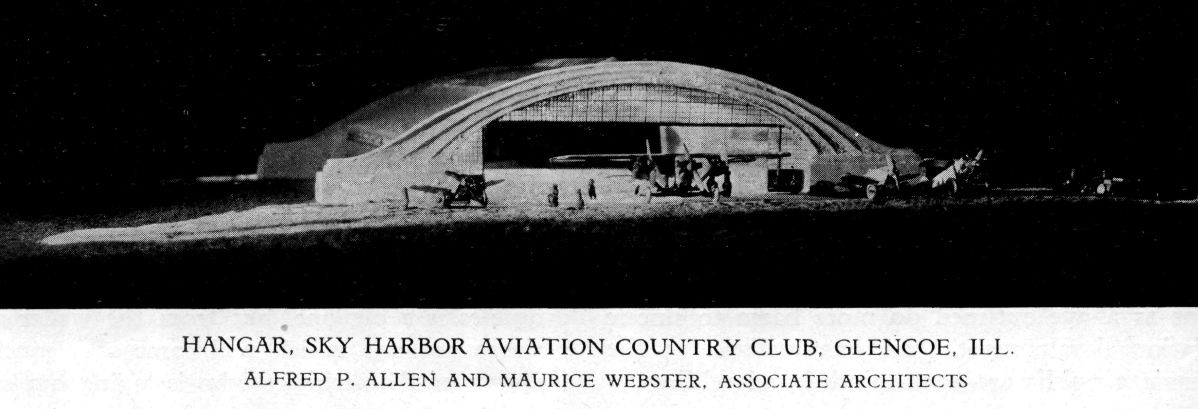

Top: Architectural Forum, 1930 Bottom Left: Realty & Building, 1965 Bottom Right: Rob Powers, A Chicago Sojurn

Likely the shortest-lived Art Deco landmark in the region was the remarkable Sky Harbor Airport Terminal building in Northbrook, by Allen & Webster, top left. Extant from just 1929 to 1939,30 this building was part of a larger airport project that included the dramatic arched hangar building seen bottom right that remains today. In 1964, the former Sky Harbor airport property was announced as the site of the nation’s first combination airfield and industrial park, bottom left a curious project that did not come to fruition.

The American Architect, 1929

Northbrook’s long-vanished Sky Harbor airport was one of 75 sites in twelve municipalities explored during our inaugural Corporate Kings North Bus Tour in September 2013. For exhaustive research on Sky Harbor, and other abandoned airports in the area, be sure to visit this fascinating web site.

Left: Pencil Points, 1939 Right: Chicago Tribune, 1938

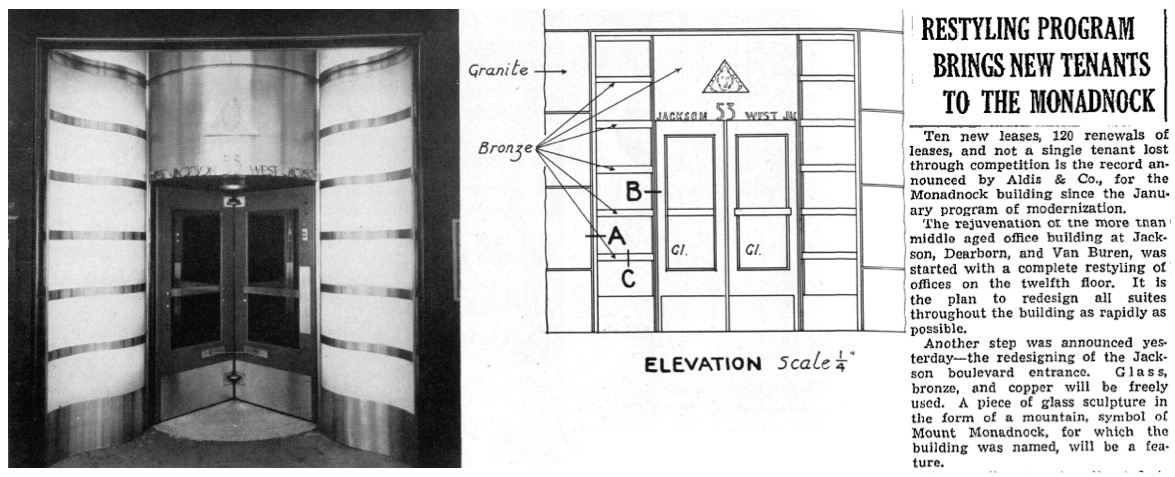

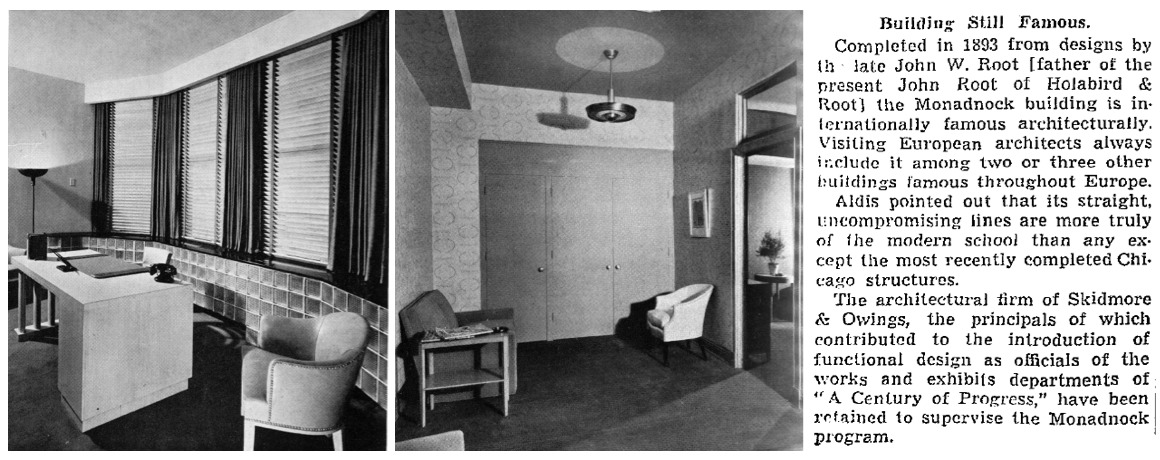

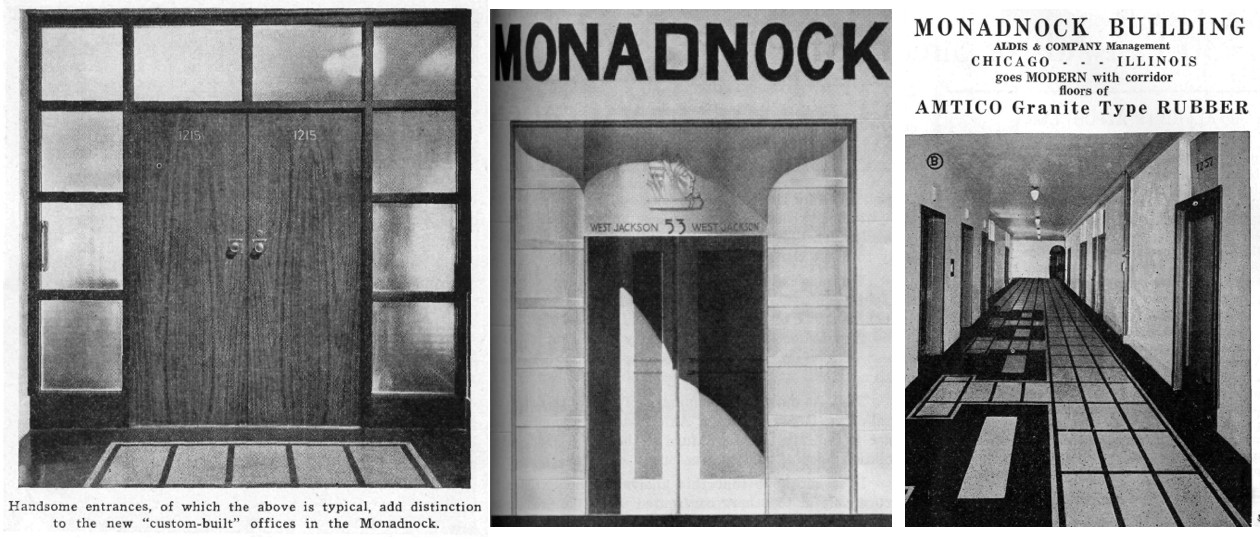

Some twenty-five years before the Hotel Brevoort’s dramatic remodeling, another aging Loop landmark also underwent a modernization. In an interesting coincidence, Louis Skidmore and Nathaniel Owings, two of the co-founders of one of the most important architecture firms in Chicago in the twentieth century, Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, remodeled one of Chicago’s most influential buildings of the nineteenth century, the Monadnock Building. The Monadnock is located on the block bounded by Jackson (main entrance shown as remodeled above), Dearborn, Van Buren and Federal Streets.

Top Left and Center: Architectural Forum, 1938 Top Right: Chicago Tribune, 1938 Bottom: The Economist, 1938

Besides an Art Deco revolving door at the Monadnock’s main entrance on West Jackson, Skidmore & Owings undertook a very period interior remodeling, including what appear to be non-functioning glass block windows underneath the building’s actual windows, above top left. No traces of Skidmore & Owing’s curious freshening are known to have survived.

Top: Forgotten Chicago Archives Bottom: Architectural Forum, 1941

The pre-World War II work of Skidmore & Owings (and later Merrill) are of great interest to Forgotten Chicago, especially since virtually none of their early work appears online or in published histories of the firm. Another recent FC find is The Circle Restaurant in the Charles A. Stevens store at 17 North State Street above; details of this project, including its custom SOM-designed furniture, were published in 1941. While the century-old Charles A. Stevens store building still stands in 2014, this retailer went out of business in the 1980s.

Forgotten Chicago has written about Skidmore & Owing’s long-forgotten low-cost housing program in Highland Park in our December 2012 research article. It is not known who designed The Circle Restaurant’s alarmingly short cherry-patterned dresses for the waitstaff, shown above.

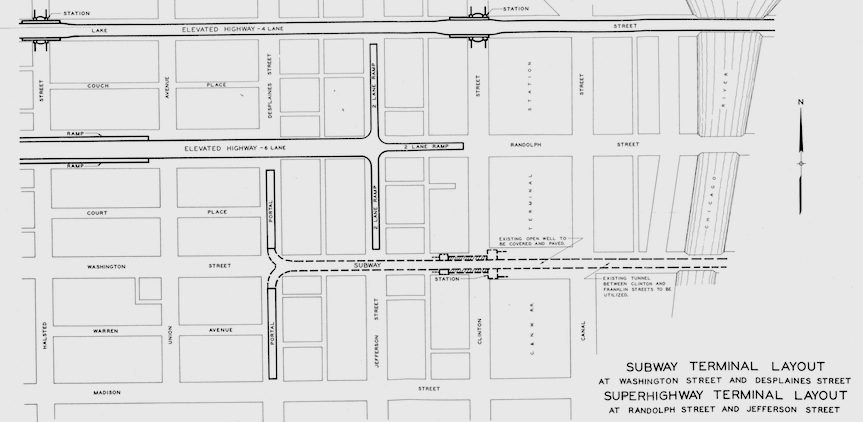

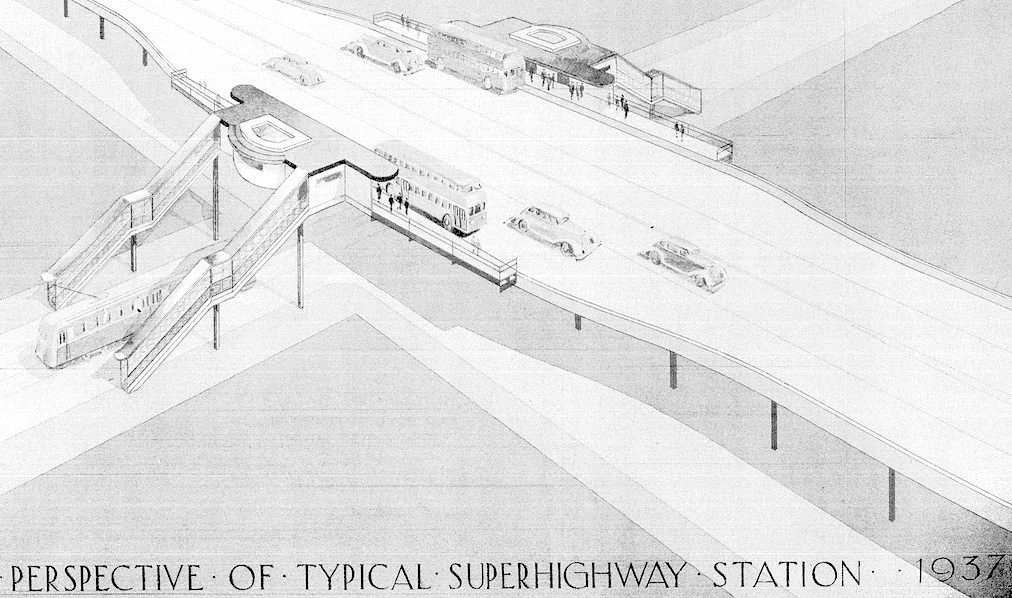

A Comprehensive Local Transportation Plan for the City of Chicago, 1937

Forgotten today, nearly 15 years before the first expressways (aka superhighways) were opened in the Chicago area, there were city-sancioned plans published in 1937 as seen above that would have radically changed the West Loop and transportation throughout the region. This ambitious plan would have turned the Lake Street Elevated into a highway, added a 6-lane viaduct above Randolph Street, and utilized the existing Washington Street tunnel to build a subway line.

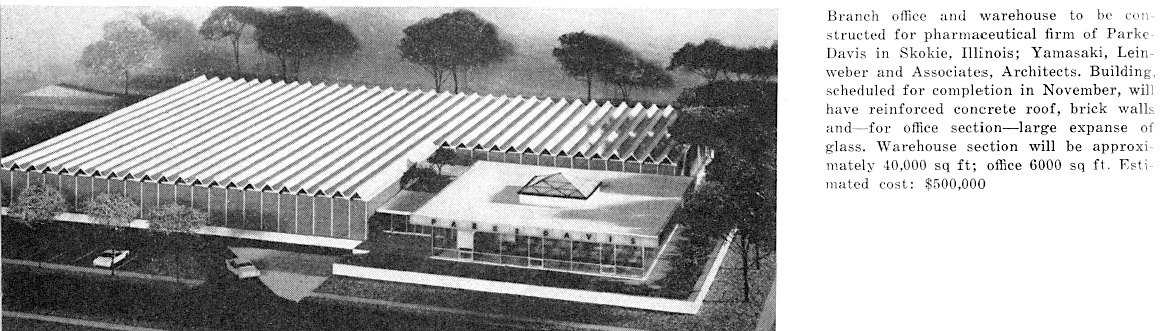

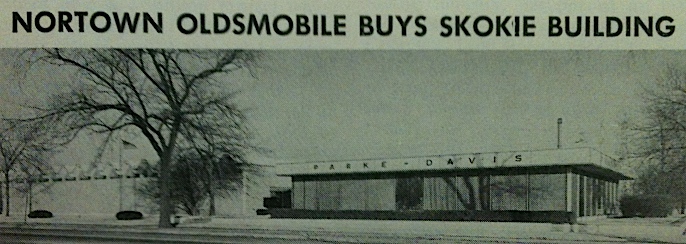

Top: Architectural Record, 1958 Bottom, Realty & Building, 1977

Another previously unknown building discovered in recent years by Forgotten Chicago was the former Parke-Davis warehouse and office in Skokie, seen above and announced in 1958. Designed by Minoru Yamasaki’s firm, architects of the original World Trade Center in New York City, this building was sold to an Oldsmobile dealer in 1977.31 The building remains a car dealership in 2014, although its distinct and intact pleated roofline was altered in 2013; participants during our Corporate Kings North bus tour in September of that year could see this drastic modification to one of only four known Yamasaki buildings in Illinois.

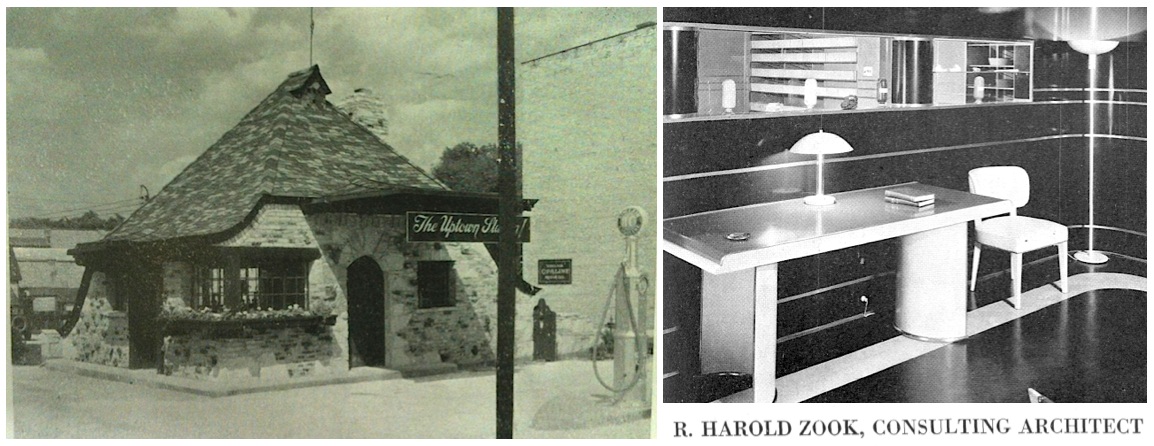

Left: American Architect, 1930 Right: Architectural Forum, 1936

The utterly unique career of R. Harold Zook (1889-1949) produced some of the most eclectic buildings in the region, from the Saint Charles Municipal Building to the Pickwick Theatre in Park Ridge, as well as many charming single-family homes. A previously unknown Zook commission was for his only known gas station design seen above left and located in Des Plaines. Another Zook project was a laboratory for the Chicago Vitreous Enamel Company of Cicero, above right; while this project is not unknown, pictures of Zook’s Art Deco interior are not known to have been republished in more than 75 years.

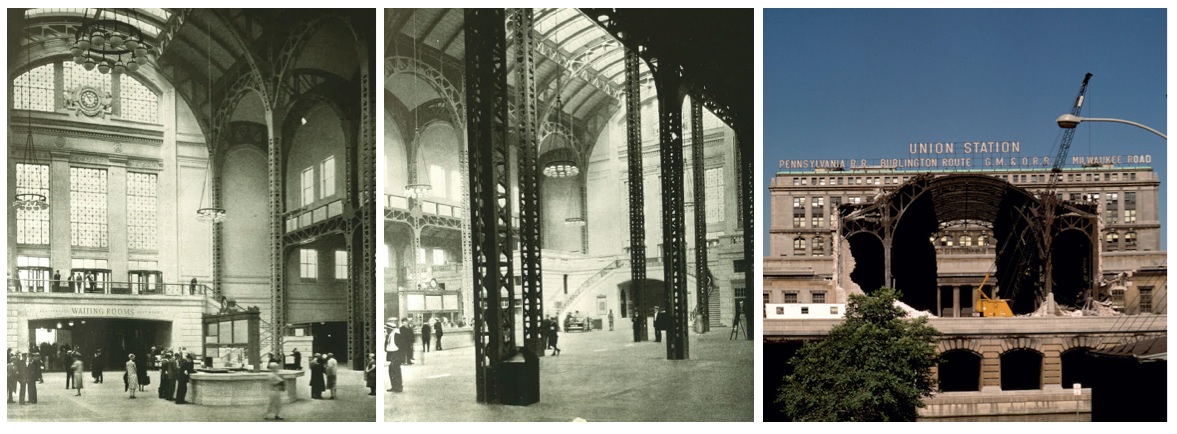

Top: Chuckman Collection Bottom Left and Center: Western Architect, 1926 Bottom Right: C. William Brubaker Collection, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1969

Following the decline in long-distance train travel, the concourse building of Union Station was demolished in 1969, with the site developed as office buildings. Photographs published in Western Architect above lower left and center in 1926 show the building’s impressive interior; at right is a picture of the building’s demolition just 43 years later. These interior photographs of the Union Station concourse are not known to have been previously republished or posted online.

Left: Western Architect, 1922 Right: Scarlet Petal Florist

The very antithesis of Forgotten, the 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition and the Museum of Science and Industry are both a permanent part of Chicago’s collective memory. Less seen, however, are interior photographs of the former Palace of Fine Arts before it underwent a major remodeling by Alfred Shaw of Graham, Anderson, Probst & White for Julius Rosenwald’s grand museum, at right.

The image above left was taken during the gala closing-night dinner for the 55th annual convention of the American Institute of Architects in 1922, with a rare view of the then-abandoned Palace of Fine Arts before it would undergo dramatic changes prior to the opening of the museum in 1933. It is not known if any of the interior details remain hidden underneath the building’s stripped-down interior.

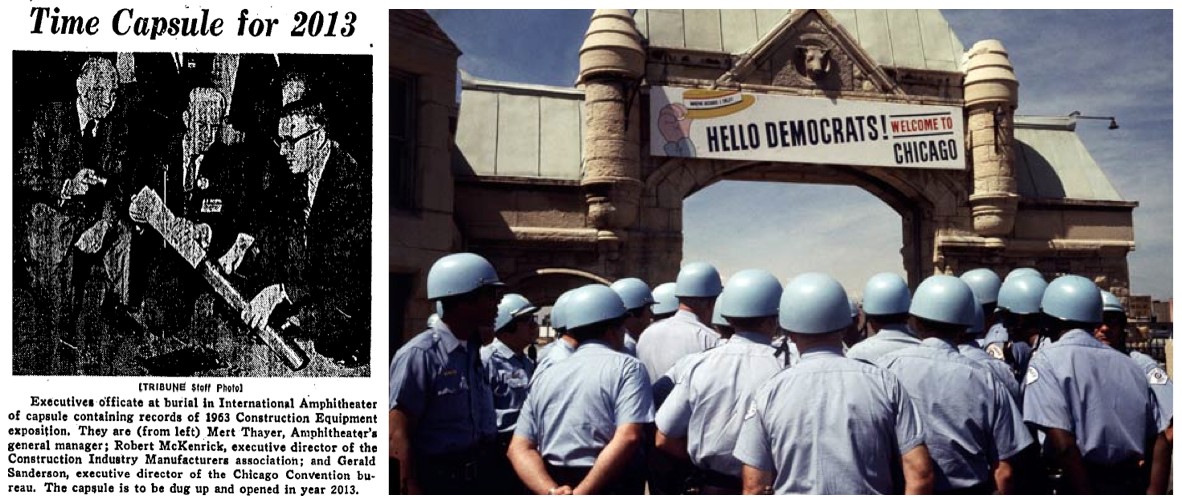

Left: Chicago Tribune, 1963 Right: Smithsonian Magazine

Scheduled to be opened in 2013, a time capsule was buried fifty years previously at the site of the former International Amphitheater, as seen above. Home to five national political conventions from 1952 to 1968, including its memorable final location for the Democratic Party in 1968 above right, the International Amphitheater was demolished in 1999. It is not known if this 1963 time capsule was unearthed during demolition, or if it remains buried at the site.

Realty & Building, 1955

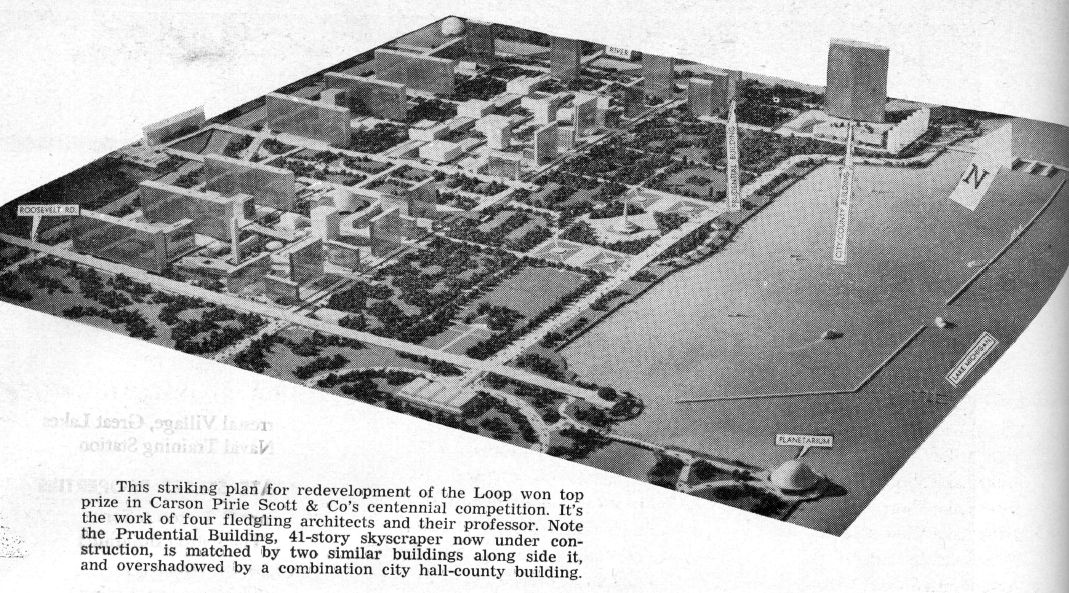

Although some of Chicago’s central area was demolished with little regard for history or architectural significance in the decades after World War II, the plan seen above showing the entire Loop and environs swept away is the most radical urban renewal plan Forgotten Chicago has yet seen. Announced in a nine-page feature in Architectural Forum in 1954,32 and sponsored by Carson Pirie Scott executive John Pirie Jr., 33 this first-place plan was conceived by students Herbert A. Tessler, Joseph A. D’Amelio, Leon Moed and William H. Liskamm with Associate Professor William N. Breger of Pratt Institute in New York City.33

Architectural Record, 1928

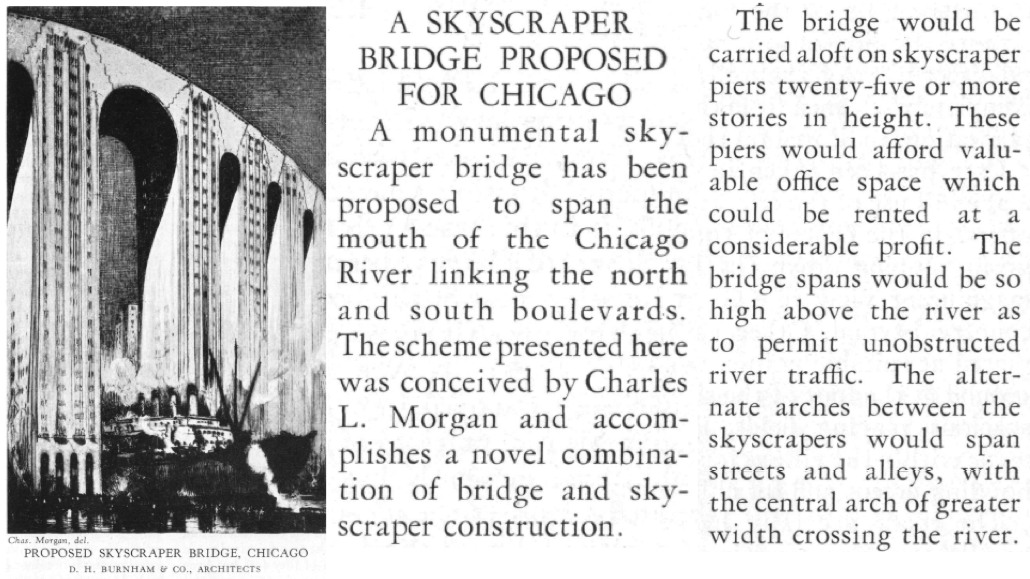

The Forgotten Chicago crew is still scratching our collective heads over this bizarre scheme to build a monstrous “skyscraper bridge” towering over Grant Park and the lakefront, published nationally in 1928. As with many somewhat ridiculous plans announced before the Great Depression, this did not make it past the rendering stage.

Left & Right: Realty & Building, 1955

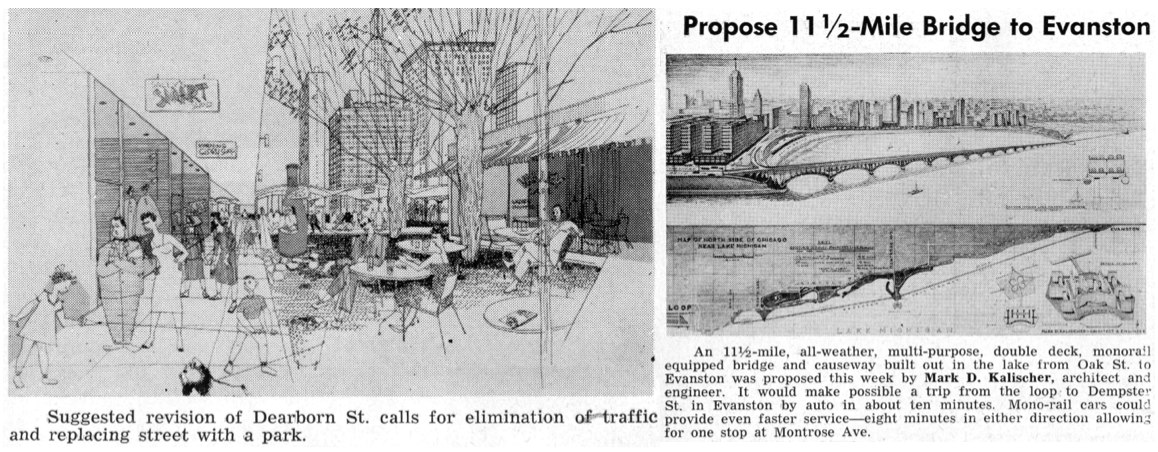

We hoped you have enjoyed this small sample of the recent research finds of Forgotten Chicago, with the 130 images shown here representing less than .008% of our current research database. As a conclusion, we wish to remind readers that much of what we think of as new ideas are often anything but: the nascent trend in cities like New York to turn over major streets to pedestrians was floated previously in Chicago nearly sixty years ago, including Dearborn Street in 1955, above left in an idea that went nowhere fast. Although Dearborn Street currently remains open to motor vehicle traffic, protected bike lanes were opened on the street in 2012.

Finally, during our August 2013 walking tour of Evanston, we shared the image above right of a wildly expensive, environmentally disruptive but highly convenient causeway (and monorai!) from Oak Street in Chicago to Dempster Street in Evanston, with a sole monorail stop inexplicably in the middle of Montrose Beach. Forgotten Chicago is looking forward to continuing our research and sharing it with those interested in Chicago’s overlooked history, architecture, and infrastructure in 2014, and in the years ahead.

Many thanks to Dennis McClendon of Chicago CartoGraphics who first alerted this author to the 1956 book Planning the Region of Chicago, an invaluable resource in explaining the vast overbuilding of the Chicago region in the 1890s and the 1920s. Dennis’ encyclopedic knowledge of the Chicago area has been utilized by the author before, and I wish to sincerely thank him for sharing his knowledge.

1 ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1990); http://search.proquest.com.covers.chipublib.org (accessed April 3, 2014).

2. Englander Co. Buys S.E Corner Michigan & Erie; Will Remodel. Realty & Building, September 17, 1949, pg. 1.

3. Ibid.

4. WOLTERS, LARRY. W-G-N OPENS NEW STUDIOS TUESDAY: WORKMEN WILL WITNESS FIRST RADIO BROADCAST. Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Sep 29, 1935; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1990), pg. SW1 (accessed January 9, 2014).

5. Morton Salt Plans 5-Story on Wacker Dr. Realty & Building, February 11, 1956, pg. 1.

6. The Other Arts: Wall Sculpture Pays Tribute to Chicago Architecture. Inland Architect, February, 1969, pg, 20-21.

7. Inflation Calculator: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm (accessed March 3, 2014).

8. What Became of the Wall. DominiNET, November 8, 2008. http://domininet.blogspot.com/2008/11/what-became-of-wall.html (accessed January 10, 2014).

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. James B. Kenyon, The Industrialization of the Skokie Area. The University of Chicago Department of Geography, Research Paper No. 33, April 1954.

13. Ibid.

14. Twenty-Five Years of Home Building in Chicago. Commerce, January 1934, pg. 115.

15. Ibid.

16. MARY ELLEN PODMOLIK. Homebuilder Pasquinelli Files for Bankruptcy. Chicago Tribune, April 8, 2011, http://articles.chicagobreakingnews.com/2011-04-08/news/29398773_1_bankruptcy-action-lists-assets-kirk-homes (accessed February 3, 2014).

17. AL CHASE. World’s Tallest Sructure for New Randolph Boulevard. Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); May 5, 1929; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1990), pg. B1. (accessed January 21, 2014).

18. Dedicate Chicago’s Tallest. Realty & Building, December 10, 1955, pg. 1.

19. School District 54 Timeline. http://ourlocalhistory.wordpress.com/school-district-54-timeline/ (accessed March 24, 2014).

20. Scottsdale Opening ‘Atomic’. Realty & Building, November 26, 1955, pg. 17.

21. Shopping Bazaar for Downers Grove. Realty & Building, December 1, 1973, pg. 7.

22. Historic Aerials, 1974 www.http://historicaerials.com (accessed February 23, 2014).

23. The Yankee Grill, Eitel Field Building Restaurant, Chicago, Illinois. Architectural Forum, November 1935, pg. 472-477.

24. Ibid.

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid.

27. Old Chicago Station Gets New Restaurant. Architectural Record, July 1940, pages 40-43.

28. Congress Casino, Chicago, Ill. Architectural Forum, June 1937, pg. 534-536.

29. Ibid.

30. http://www.airfields-freeman.com/IL/Airfields_IL_Chicago_N.htm#skyarbor (accessed March 3, 2014).

31. Nortown Oldsmobile Buys Skokie Building. Realty & Building, August 27, 1977, pg. 7.

32. Bold Plans for Chicago. Architectural Forum, November 1954, pg. 122-130.

33. Ibid.

- Chaddick Institute Webinar on Wednesday, May 12, 2021: Illinois Center & Lakeshore East: Rail to Real Estate

- Chicago’s Shoreline Motels – South

- Bertrand Goldberg in Tower Town Part 2: Postwar Development of Michigan & Pearson

- Bertrand Goldberg in Tower Town Part 3: Bertrand Goldberg’s Michigan Avenue Project

- Good Modern: The Forgotten Work of James F. Eppenstein, Part 1