Institutions, 1953

This is the second of three Forgotten Chicago articles on the work of modernist architect and designer James F. Eppenstein. For background on Eppenstein’s prolific career, his hotel and a distinctive train that once ran from Chicago to Milwaukee, visit Part One of this series.

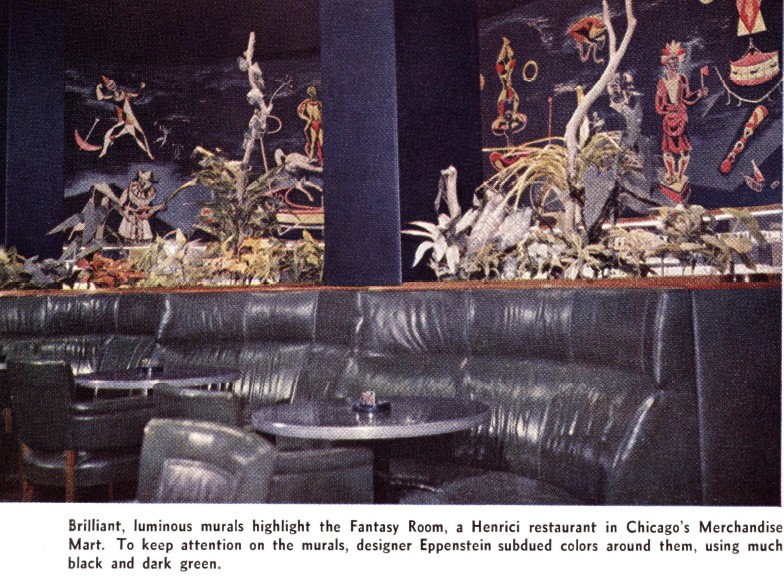

Seen above is a rare color photograph of Eppenstein’s interior of Henrici’s long-time location at Chicago’s Merchandise Mart, featuring a mural by Felix Ruvolo. More information on this project, Henrici’s and their parent company Thompson’s, and Felix Ruvolo follows below.

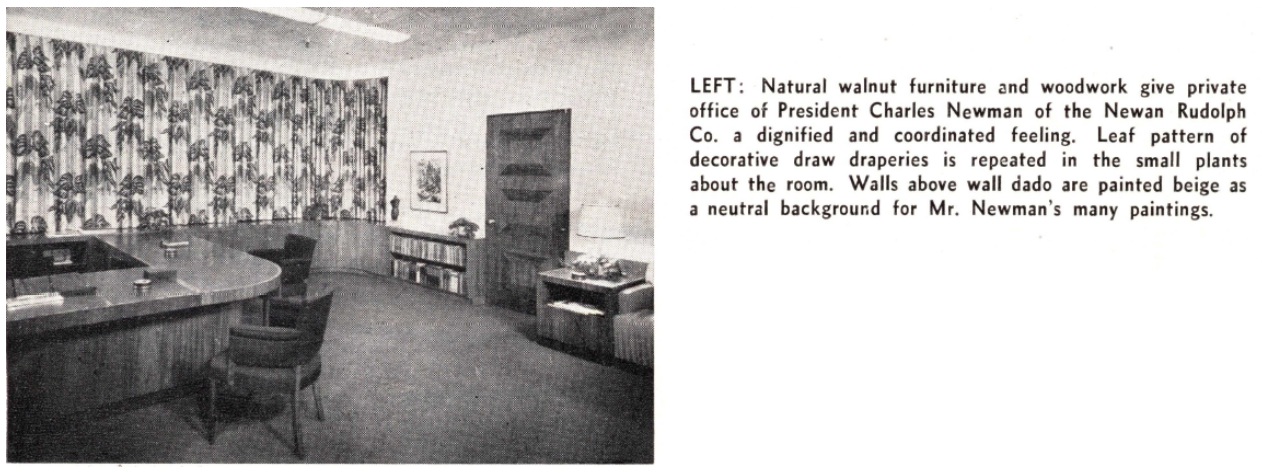

Realty & Building, 1947

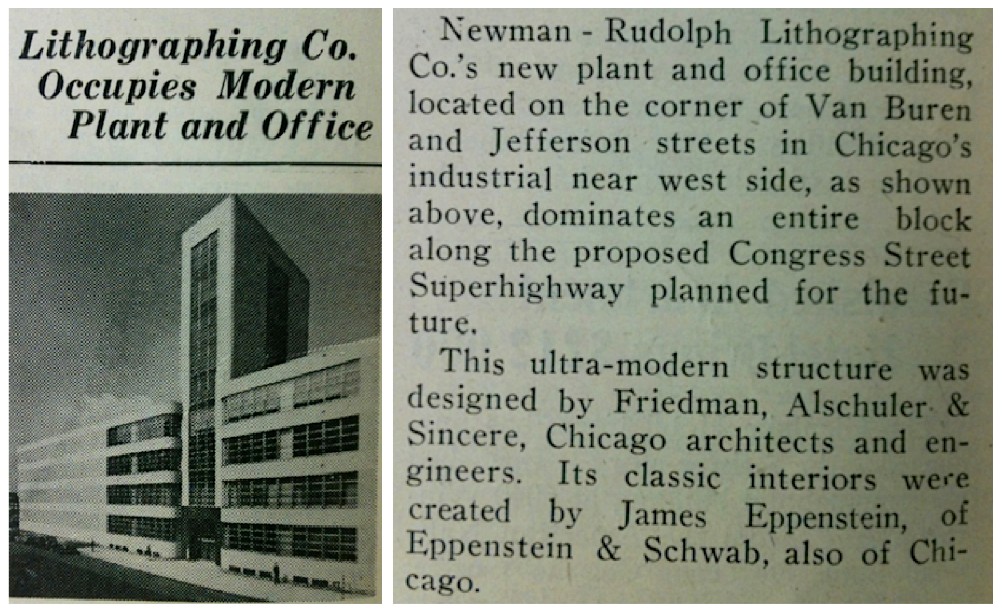

James Eppenstein’s work and career first came to Forgotten Chicago’s attention in late 2011 while we were researching the former Newman-Rudolph Lithography Company at 400 South Jefferson Street by Friedman, Alschuler and Sincere, above. This overlooked landmark was about to undergo a major renovation for the corporate headquarters of the newly named Hillshire Brands, which had been split off from Sara Lee and was moving their main office from Downers Grove to Chicago.

While reading a non-digitized 1947 issue of Realty & Building, the source of over 6,000 articles and images in the Forgotten Chicago database, it was noted that James Eppenstein and his firm Eppenstein & Schwab had designed the building’s “classic” interiors, notably the entrance lobby and main stair hall, seen below.

Perkins+Will, February 2012

An inspection by the FC crew in December 2011 to the interior of the mostly vacant building showed all of Eppenstein’s details still intact nearly 65 years after this building was completed. This then-intact and endangered interior by was discussed during our FC175 event in March 2012, and this building was the first stop on our August 2012 Corporate Kings of the Suburbs tour. With the conversion of this building that year to the new headquarters building for Hillshire Brands, Eppenstein’s interior details appear to have been removed.

Top: Chicago Tribune, 1945 Second and Third from Top: Institutions, 1953 Bottom: Eppenstein family collection

While this former printing plant is one of countless overlooked and under-studied industrial facilities in the Chicago area, Newman-Rudolph was particularly noteworthy. Planning for the facility started in 1943, and ground was broken in September 1945, just weeks after combat in World War II ended.1 The building’s air conditioning system maintained ideal printing conditions during Chicago’s often severe climate, with a variation throughout the year of just one degree in temperature and one percent humidity.2

Above are contemporary views of Newman-Rudolph’s interior. The two images at the bottom show a mural by Felix Ruvolo, who would soon collaborate with Eppenstein on the Henrici’s at the Merchandise Mart.

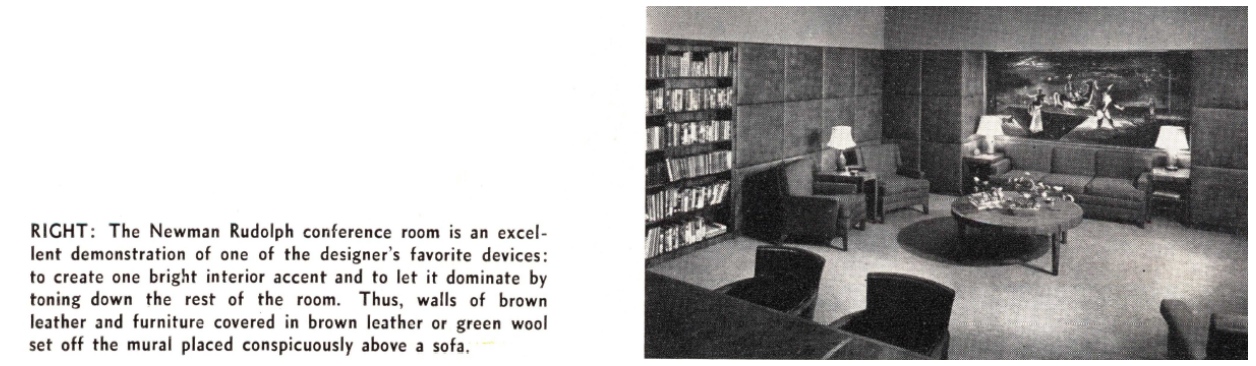

Left: James F. Eppenstein, Architect, Architectural Catalog Co., Inc., 1938 Right: Architectural Record, 1939

Pencil Points, 1942

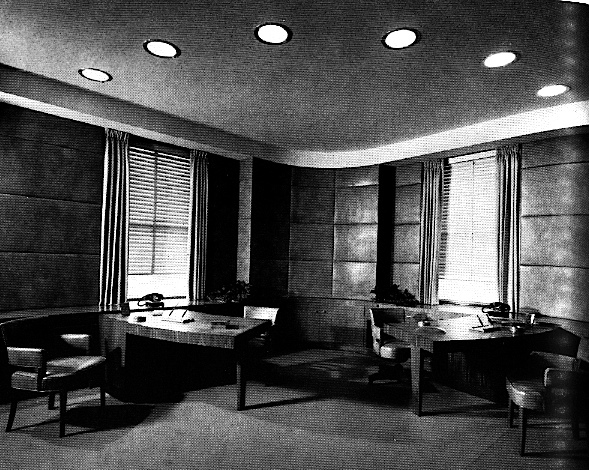

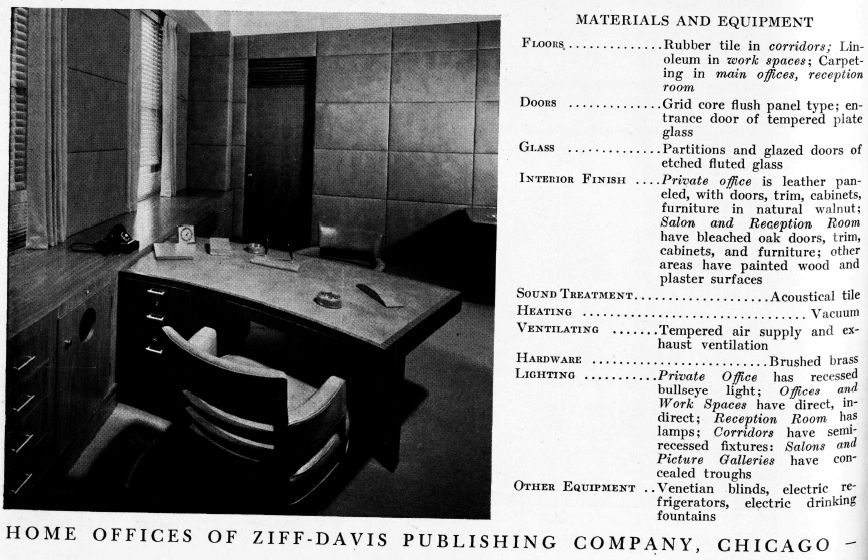

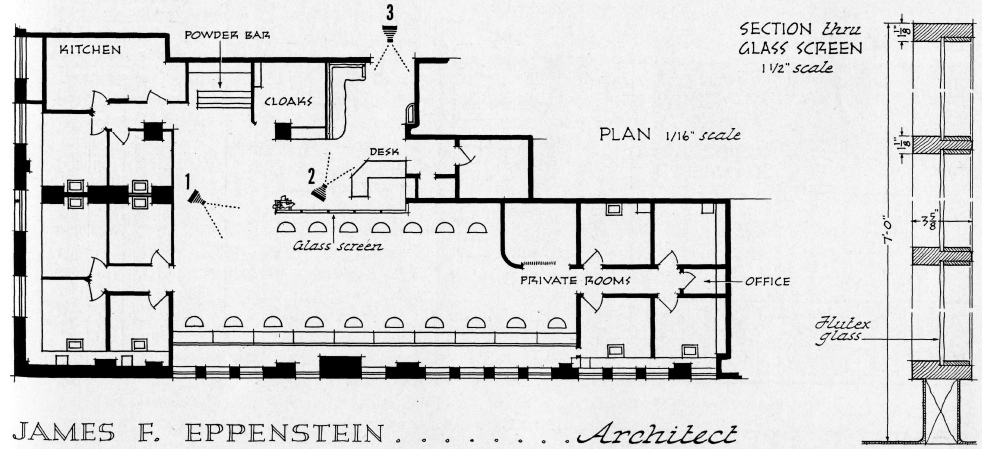

Another commercial interior remodeling by Eppenstein and his business partner Raymond Schwab was for the Ziff-Davis Publishing Company at 185 North Wabash Avenue.3 Ziff-Davis was established in Chicago in 1927, and moved by 1942 from the heart of Printers Row at 608 South Dearborn Street4 to the northern end of the Loop, in this building facing the Lake Street “L” tracks at Wabash.

Pencil Points, 1942

It is highly unlikely that any of the Ziff-Davis interiors pictured above are extant in 2013. This building now goes by the address of 63 East Lake Street and is home to MDA City Apartments. This building has previously been included in Open House Chicago; if it is included again in the future, the building’s extensive rooftop amenities and spectacular views are well worth a visit.

Pencil Points, 1942

As with Eppenstein’s own office, discussed in part one of this series, little expense was spared for Ziff-Davis. Listed above are some of the materials used, including leather and walnut paneled walls, brushed brass, rubber floors, and fluted glass, which would appear repeatedly in Eppenstein’s work.

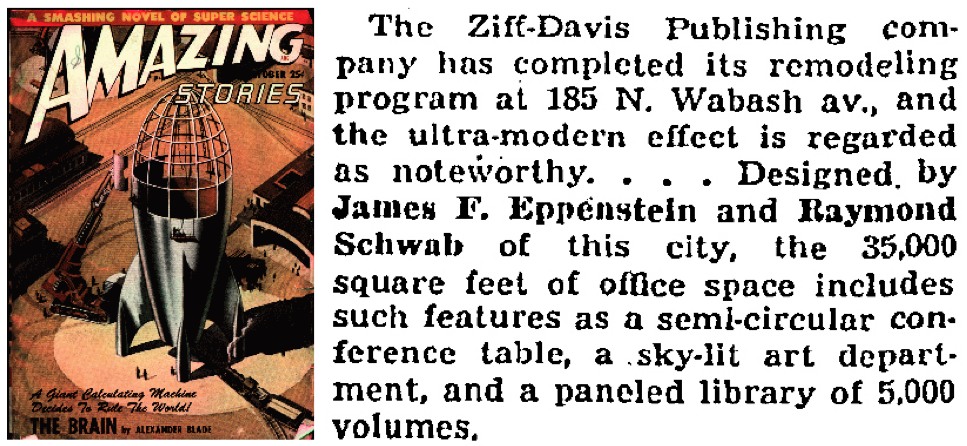

Eppenstein & Schwab would remodel the Ziff-Davis offices twice. While the images displayed here are from the original 1942 project, five years later the Chicago Tribune reported that the firm had completed an “ultra-modern effect” for this publisher,5 below right. Published photos of the second Ziff-Davis remodeling have not been located as of this writing.

Left:Space Museum, National Aeronautics and Space Administration Right: Chicago Tribune, 1947

Eppenstein was an appropriate choice to remodel the office of Ziff-Davis, as his modernist style was well-suited to this publisher’s technology and science fiction titles, including Amazing Stories above left. After a series of ownership changes, Ziff-Davis no longer has an office in Chicago.

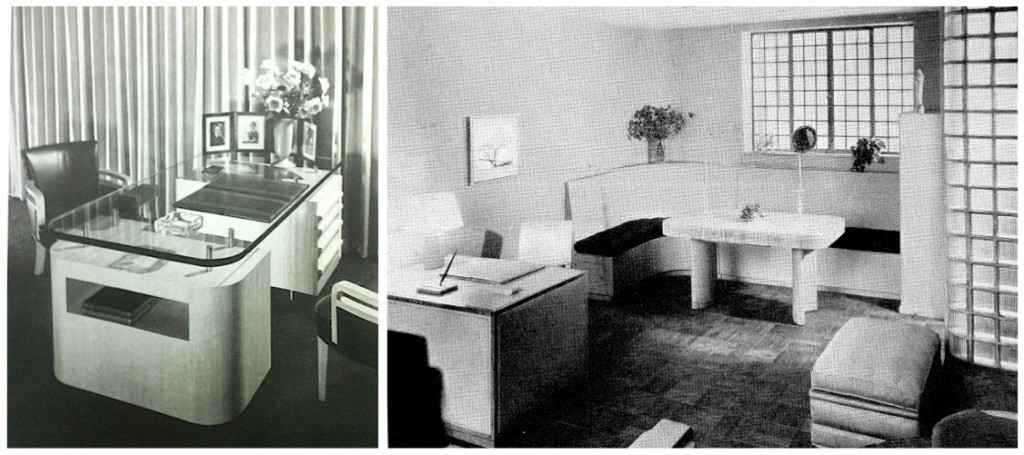

Pencil Points, 1941

In 1940, Eppenstein was hired to design a beauty parlor for the swank Saks Fifth Avenue store, located at the time at 669 North Michigan Avenue, below right. This project was featured in the magazine Pencil Points (seen above), which would later be renamed Progressive Architecture.

Left: Architecture, 1930 Right: Courtesy of Jacob Kaplan, no date

Saks had relocated from their original home at the southwest corner of Michigan and Chestnut to the northeast corner of Michigan and Erie in January 1936.6 The northern portion of this building was originally designed by Philip Maher for Stanley Korshak’s Blackstone Shop, opening in the building above left in February 1930.7

For the relocated Saks store, this building was expanded and remodeled by Holabird & Root8 seen above right. Nearly 85 years after opening, elements of the original building may still be seen; what appear to be the original windows on the north side of the building, barley visible above far left, could still be seen from the alley east of this building in 2013.

Pencil Points, 1941

Although Eppenstein’s great skill as an interior architect is evident in the image above, he was an unusual choice for this project. In describing this store prior to its 1936 opening, Saks president Adam Gimbel remarked, “It is to be entirely a feminine store. Nothing in the decorations will appeal to the masculine sex.”9 Eppenstein’s later remodeling and extensive use of translucent Flutex glass and other hard surfaces is seemingly at odds with a “feminine” décor. The view above corresponds to the camera icon “1” in the illustrated floor plan.

Later additions were made to this retail building, including the current nine-story addition to the south, which remains on this site today. Saks would later move again, across the street and further north to Chicago Place at Michigan and Superior. As of late 2013, the former Saks Fifth Avenue location houses a Garmin showroom and Niketown.

Top: Courtesy of the Eppenstein Family Bottom: Patrick Steffes, September 2013

South of Motor Row, on Wabash Avenue and adjacent to an entrance ramp for the Stevenson Expressway, is an intact 1948 Eppenstein commission for the Leterstone Sales Company. Upon completion, “LETERSTONE SALES CO” was spelled out above the entrance, and this building featured a continuous band of Flutex glass in the window on the second floor, both of which have since been removed. Forgotten Chicago located this project by reviewing a period telephone directory, where it was listed as an auto accessories company.10 A portion of the vast McCormick Place complex may be seen in the bottom photo at left.

Patrick Steffes, September 2013

Jacob Kaplan, May 2014

The Leterstone building shows many trademarks of Eppenstein’s work, including ribbon windows, the use of exterior limestone and contrasting granite, and Flutex glass near the entrance, all of which are still intact. As of this writing, nothing additional is known about this company or their history following the completion of their 1948 Eppenstein building. This then-abandoned building was a featured stop during Forgotten Chicago’s inaugural South Loop walking tour in May 2014.

Left: Curbed Chicago Right: Baderbrau Brewing Company

In December 2014, it was announced that Baderbrau, one of Chicago’s pioneer craft brewers (1989-1997 and 2012-present) would be remodeling and moving into Eppenstein’s former Leterstone Sales Company. This location is planned to open in Summer 2015, as detailed here. This facility is planned to include a brewery, taproom, and retail space.

Courtesy Chicago Tribune and Blue Star Properies

The cavernous interior of the future Baderbrau Brewing Company is shown above prior to renovation work. Upon opening, this will be one of the only Eppenstien-designed interiors open to the public, and it is hoped that this building’s distinctive exterior facing South Wabash Avenue will be preserved as much as possible.

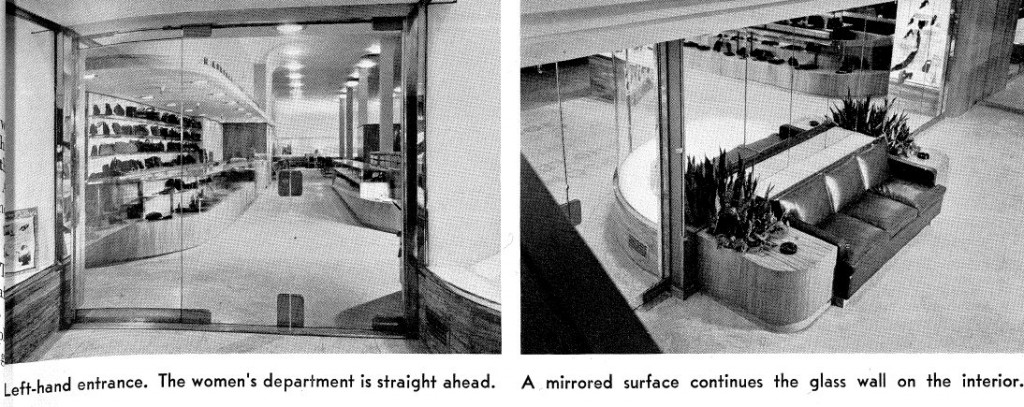

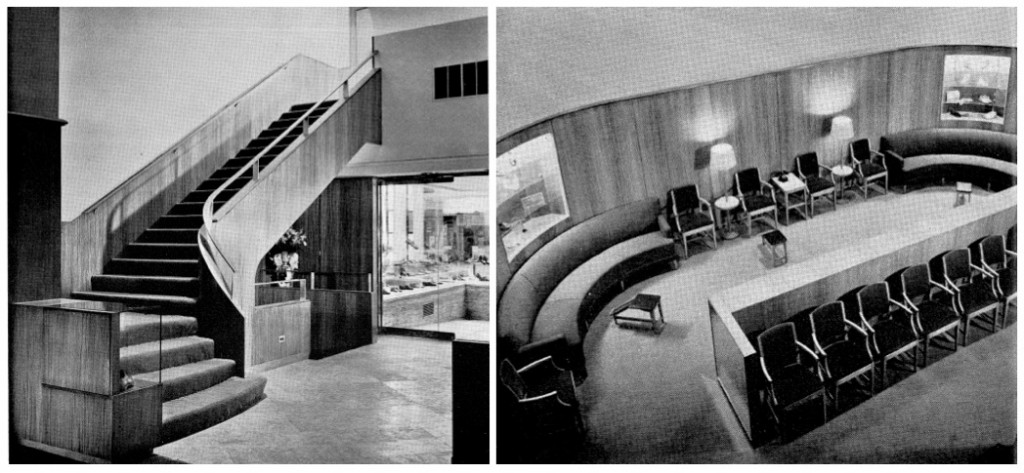

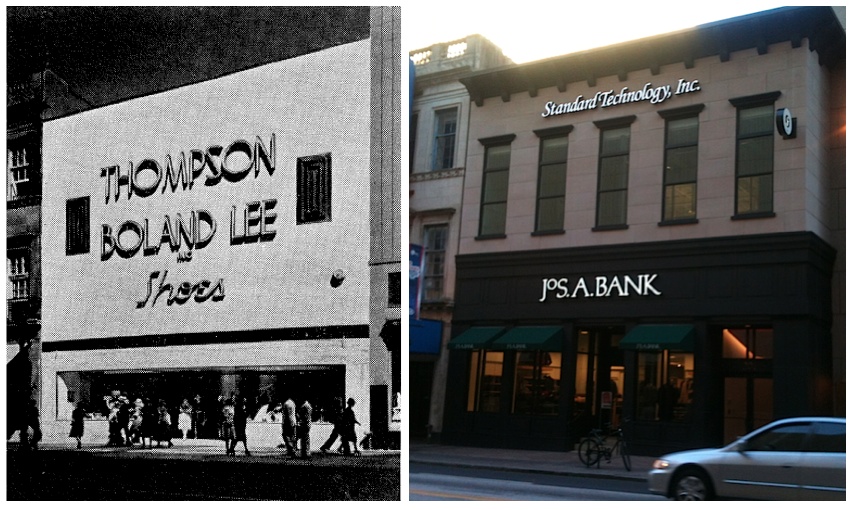

Architectural Record, 1939

Although Forgotten Chicago has identified more than 75 Eppenstein buildings and interior remodelings, we know of only three retail store projects. Besides the Saks Fifth Avenue beauty salon and a modest 1930s Floresheim Shoe Store at 100 North Wabash Avenue,11 his only other known retail commission was for a large, two-story Thompson Boland Lee Shoe Store in Atlanta, Georgia, published in 1939, above and below.

Architectural Record, 1939

Compared with other retail store designs of the late 1930s, Eppenstein’s work may be seen as rather restrained. The architect of record for this store was the prolific Atlanta firm of Ivey & Crook; Eppenstein was listed as “Designer and Consultant.”12 Since no project list or archive of Eppenstein’s work other than Forgotten Chicago’s research has been found as of this writing, it is not known if additional projects were completed for this shoe retailer.

Top Left: Architectural Record, 1939 Top Right: Patrick Steffes, January 2014 Bottom: Special Collections Department, Pullen Library, Georgia State University, no date

Although downtown Atlanta has experienced an enormous amount of demolition and reconstruction in the decades since this shoe store was completed, this building at 201 Peachtree Street NE is still standing. Heavily altered, the store now has the appearance of a building from the nineteenth or early twentieth century.

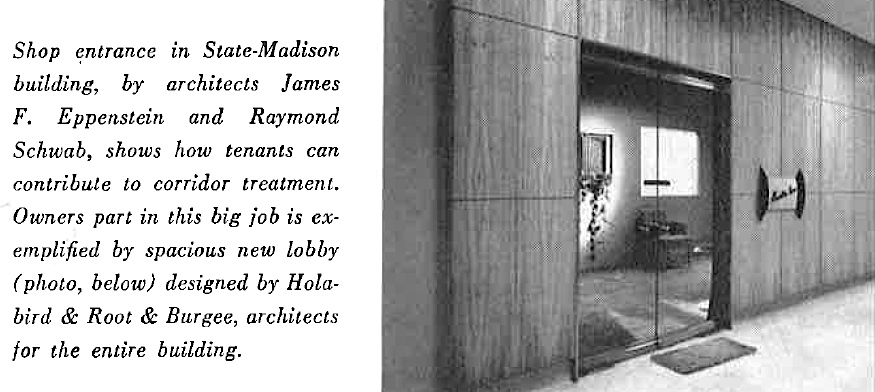

Architectural Forum, 1950

One of the last known commercial projects by Eppenstein and his business partner Raymond Schwab was an interior remodeling of what was then known as the State-Madison Building, at the northwest corner of Chicago’s most iconic intersection. Published in 1950, this project included remodeling of the second and third floors for shops, with an exterior remodeling by Holabird & Root & Burgee. This building currently houses a Sears store.

Architectural Record, 1945

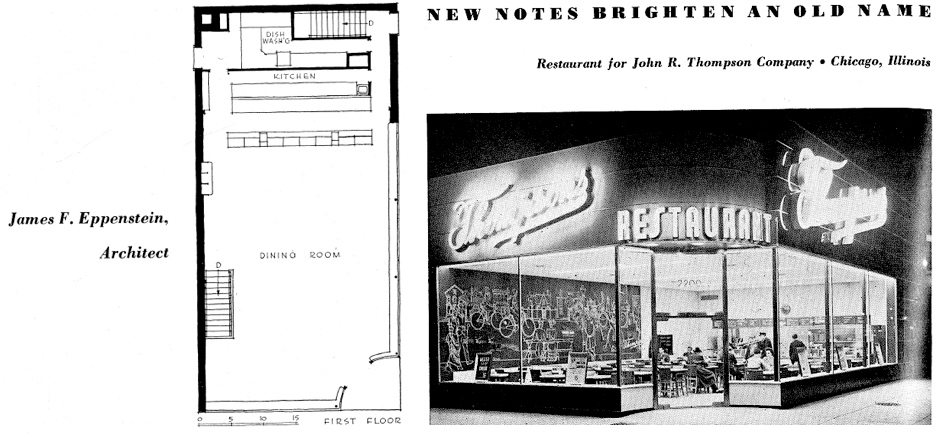

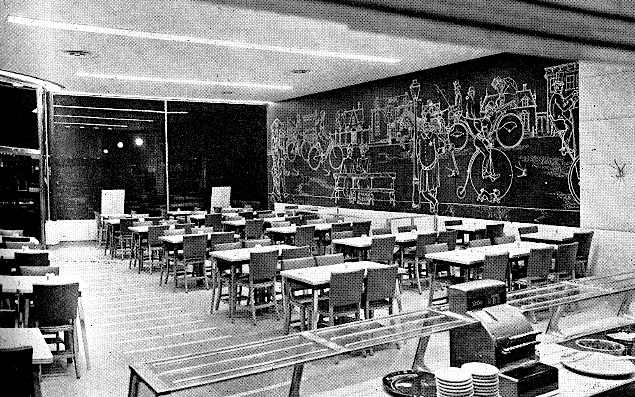

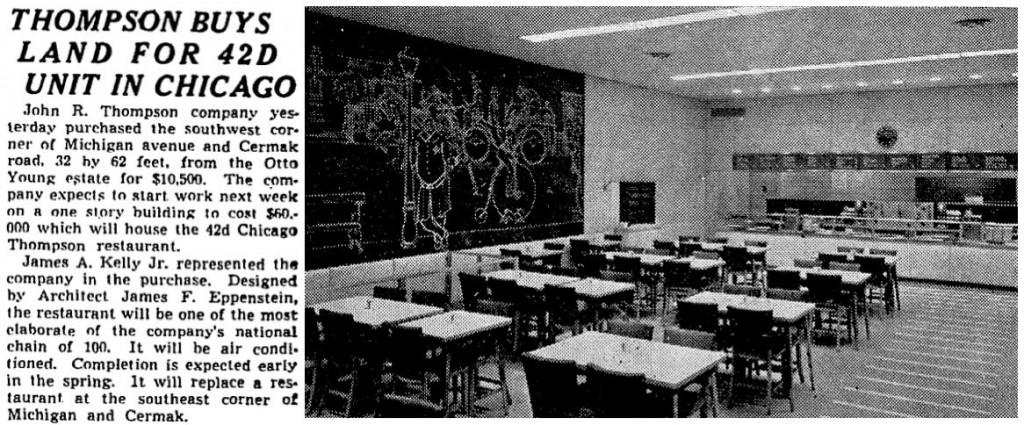

Near the Leterstone building, at the busy corner of South Michigan Avenue and East Cermak Road, is another Eppenstein commercial building still extant at this writing. The images above for a unit of Thompson’s Restaurants and the pictures that follow were published in 1945; this project was completed in early 1942.13

Architectural Record, 1945

Although when it opened it was located one of the largest and most concentrated districts of automobile showrooms in the U.S., the mural by an unknown artist seen above features, perhaps ironically, a parade of old-timey bicycles. While the building footprint and chimney remain as built in 2013, it is not known if this whimsical mural is still intact under the interior walls of the current tenant of this building.

Left: Chicago Tribune, 1941 Right: Architectural Record, 1945

Eppenstein’s attention to detail for this “elaborate” restaurant, which was essentially a quick-service and low-cost cafeteria, was extraordinary. As noted in a 1945 article on this Thompson’s location in Architectural Record, “Coffee with cream in it and butter are particularly susceptible to odd color effects, and considerable study went into choosing fluorescent that would not spoil appetites.”14 For James Eppenstein, how butter and cream would appear after dark was not something to be overlooked.

Left: Chuckman Collection, no date Right: Restaurant-ing through history

Thompson’s was a Chicago-based chain of affordable restaurants with locations throughout the city and the U.S.; the former Thompson’s headquarters and flagship restaurant at 350 North Clark Street noted above left has been visited previously on several Forgotten Chicago tours. Thompson’s was a major restaurant chain in Chicago by the 1940s; as noted above, the Motor Row location was the 42nd for the chain in Chicago.

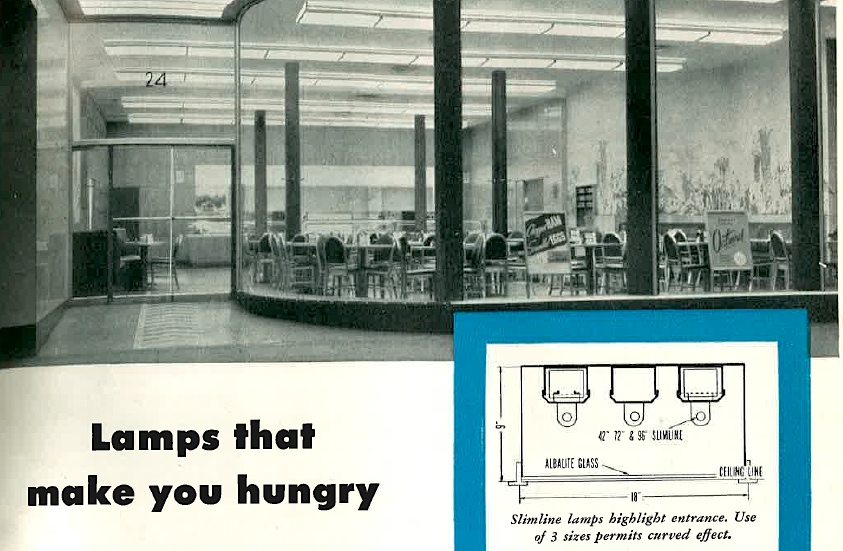

In 1947, Eppenstein redesigned the interior and exterior of the Thompson’s location at 24 West Monroe Street, in a $125,000 modernization.15 This location was just west of the Schubert Theatre in what appears to be a building from the nineteenth century, as seen above. A closeup is seen below; note the prominent mural and enormous exterior windows. This building would later be demolished less than ten years later for the Inland Steel Building.

General Electric advertisement, 1949

In October 1956 it was announced that the Thompson’s Motor Row location would be acquired by competing restaurant chain Pixley & Ehlers, along with seven other Thompson’s locations.16 These Thompson’s were sold in order to finance a new Holloway House Cafeteria (also a unit of the John R. Thompson Company) at 10035 North Skokie Boulevard just north of Old Orchard Road in Skokie, along with a two story motel on the same site.17

Chuckman Collection, no date

In 1956, the area around the newly opened Old Orchard Mall was experiencing rapid commercial development. Although the Holloway House was built,18 the motel does not appear in aerial views of that location.19 The Holloway House project in Skokie was across the street from the deluxe Maurice L. Rothschild’s store seen during the September 2013 Forgotten Chicago Corporate Kings North bus tour; rare and remarkable photos of the now partially demolished Rothschild’s store by the prolific Chicago-based architectural firm Epstein may be seen here.

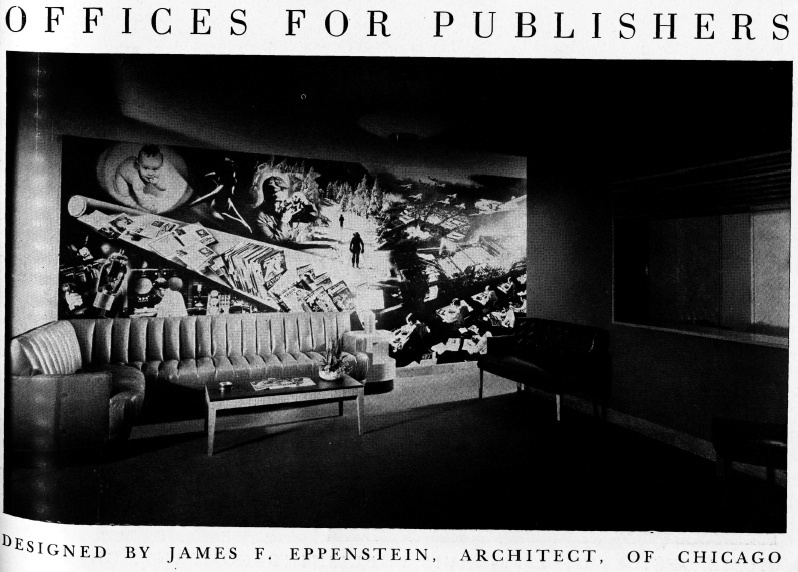

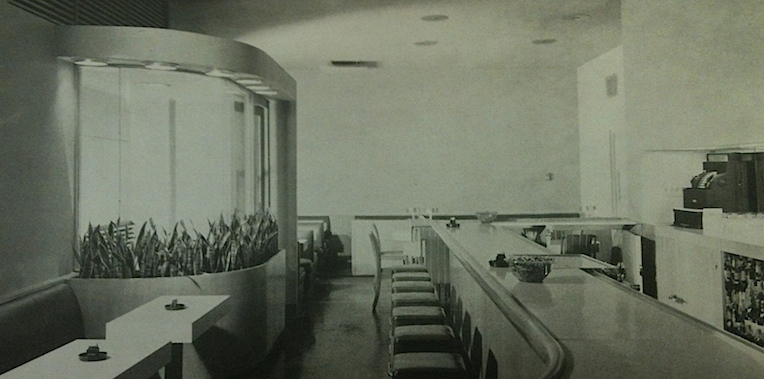

Architectural Record, 1948

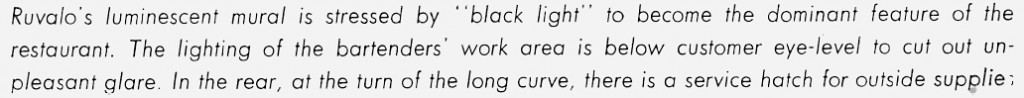

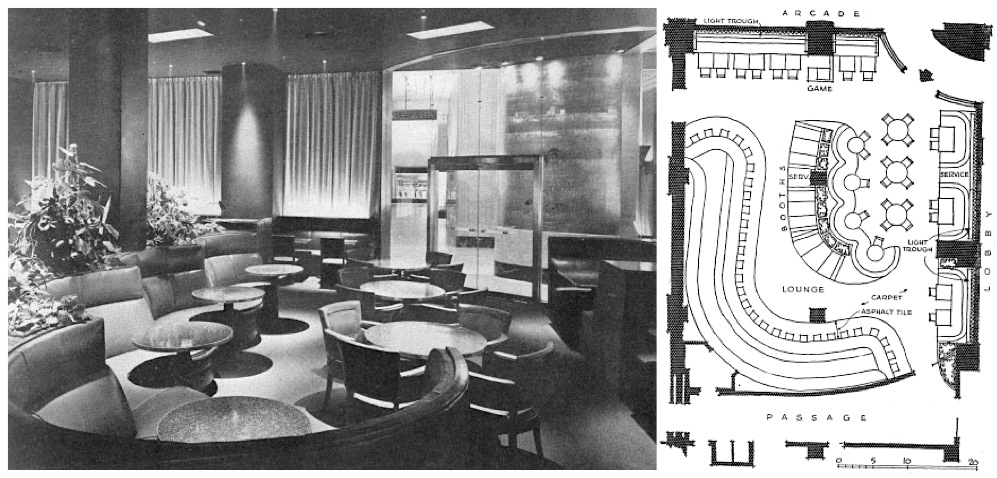

In 1929, the John R. Thompson Company acquired the legendary restaurant Henrici’s, which first opened in Chicago in 1868.20 Henrici’s flagship West Randolph Street location was demolished for the Civic Center (later Richard J. Daley Center) following its closure in 1962. Mostly forgotten today, however, were the other Henrici’s operated by Thompson’s, including a location at the Merchandise Mart. In 1947, Eppenstein and his business partner Raymond Schwab were hired to modernize this existing location;21 the images above and below were first published in 1948, and have not been republished widely or posted online.

Architectural Record, 1948

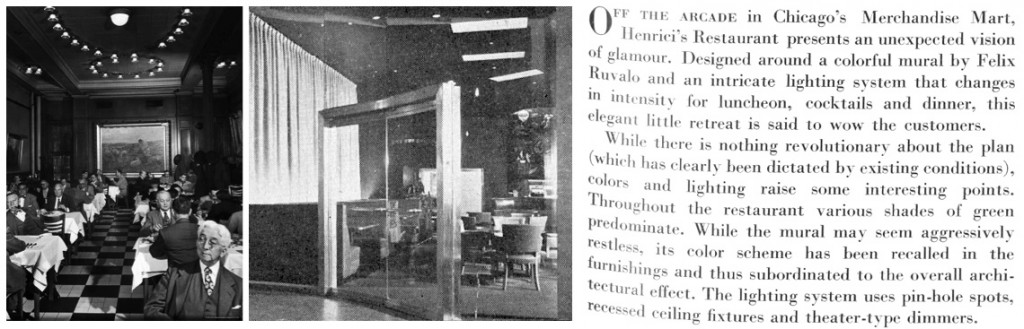

The results of this high-profile restaurant and bar commission in what was then the world’s largest commercial building were spectacular. Besides many signature features of Eppenstein’s modernist style such as custom furniture, extensive use of glass and deluxe materials, the project also featured another whimsical mural, this one by noted artist Felix Ruvolo.22 The mural by Ruvolo (often spelled incorrectly as Ruvalo) featured luminescent paint which would glow under black lighting; the overall light levels of the restaurant would dim as they day progressed.23

Top and Bottom Center and Bottom Right: Architectural Record, 1948 Bottom Left: Calumet412

Eppenstein and Schwab’s redesign of the Merchandise Mart Henrici’s could hardly have been more different from their location on West Randolph Street, above bottom left. The entrance to the first floor arcade of the Mart was a glass wall, and the serpentine arrangement of the bar and seating area were in stark contrast to the very formal arrangement seen at their Loop location. As with many other Eppenstein projects, the later history of the Henrici’s in the Merchandise Mart, or the fate of the Felix Ruvolo mural was saved, is not known.

James F. Eppenstein, Architect, Architectural Catalog Co., Inc., 1938

An early restaurant commission was published in 1938 for a buffet and bar in the Civic Opera Building above at 20 North Wacker Drive, named Opera Buffet. Eppenstein’s patented cantilevered ashtrays, discussed in part one of this series, appear on the tables and the bar. As of this writing, no additional published photographs or ephemera for this project have been found.

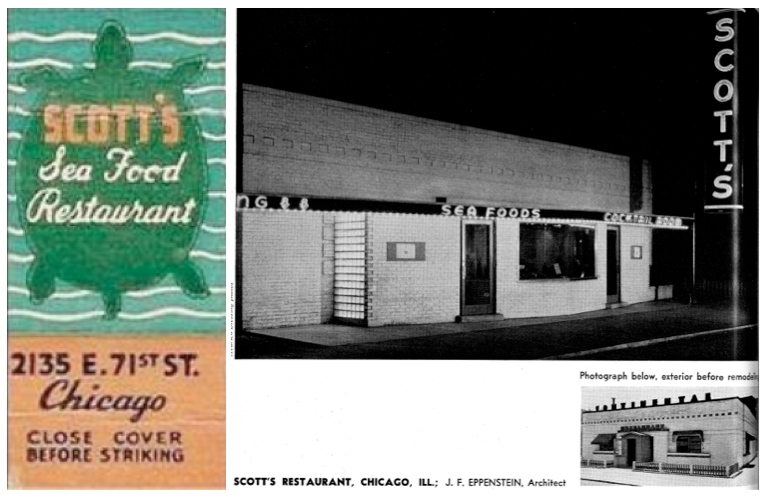

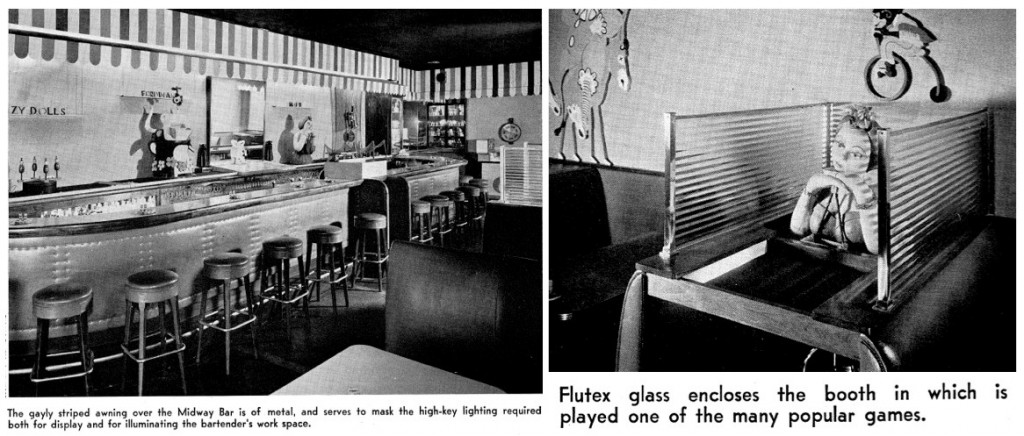

Upper left: Chuckman Collection Remaining Photos: Architectural Record, 1940

In the late 1930s, Eppenstein remodeled Scott’s Restaurant at 2135 East 71st Street, in Chicago’s South Shore community. Besides an exterior remodeling, Scott’s featured three distinct public spaces, including a restaurant section, a bar, and the “Hunt Room” cocktail lounge. 24 The bar was “designed to resemble a midway, with games for the amusement of patrons.”25 Above right may be seen one of these peculiar games. The later history of Scott’s and this building is also not known, and the site is currently a vacant lot.

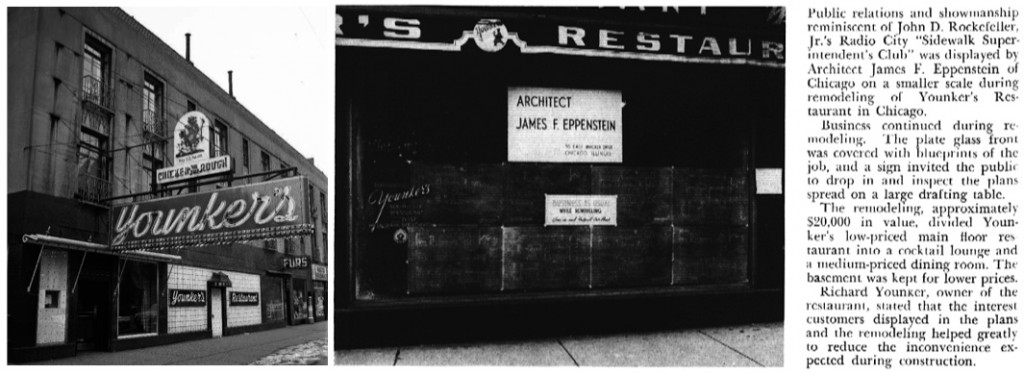

Left: Craig’s Lost Chicago, no date Right: Pencil Points, 1941

Two additional Eppenstein restaurant projects were completed by 1941 for Chicago restaurant Younker’s, at 51 East Chicago Avenue above left and 1510 East Hyde Park Boulevard26 above right. No published photographs of these restaurant interiors have been located, and both of these buildings have been demolished.

Part Three of this series will focus on Eppenstein’s residential projects, including apartments and single-family homes.

1. Plan 2 Years, Ready to Build W. Side Plant. Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Aug 26, 1945; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1990), pg. A6 (accessed December 14, 2013).

2. Ibid.

3. Illinois Bell Classified Telephone Directory for Chicago. Chicago: The Reuben H. Donnelley Corporation with permission of the Illinois Bell Telephone Company, September 1942.

4. Illinois Bell Classified Telephone Directory for Chicago. Chicago: The Reuben H. Donnelley Corporation with permission of the Illinois Bell Telephone Company, November 1941.

5. Magazine of BOOKS: AMONG THE AUTHORS. Babcock, Frederic. Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); May 4, 1947; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1989), pg. B5 (accessed November 10, 2013).

6. Saks to Open in New Location. Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Jan 19, 1936; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1989), pg. A6 (accessed November 14, 2013).

7. Display Ad 25 — No Title; Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Feb 2, 1930; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1989), pg. 28 (accessed November 14, 2013).

8. Michigan Ave. Improvement: Saks-Fifth Avenue to Move to 669 North Michigan Ave. Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Jun 30, 1935; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1989), pg. A12 (accessed November 3, 2013).

9. MICHIGAN AVE. IMPROVEMENT: Saks-Fifth Avenue to Move to 669 North Michigan Ave. Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Jun 30, 1935; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1989), pg. A12 (accessed November 10, 2013).

10. Illinois Bell Classified Telephone Directory for Chicago. Chicago: The Reuben H. Donnelley Corporation with permission of the Illinois Bell Telephone Company, September 1949.

11. Chicago History Museum ARCHIE collections database, http://www.chsmedia.org:8081/ipac20/ipac.jsp?profile=, (accessed November 3, 2013).

12. Atlanta, GA: Three Shops in One Store for Mixed Clientele. Architectural Record, January 1840, pg. 42-45.

13. Thompson Buys Land for 42D Unit in Chicago. Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Dec 18, 1941; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1989), pg. 36 (accessed November 10, 2013).

14. New Notes Brighten an Old Name Restaurant for John R. Thompson Company, Chicago, Illinois. Architectural Record, October 1945, pg. 116-117.

15. Thompson’s New Units to Be Dissimilar. Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Mar 16, 1947; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1989), pg. SA (accessed November 23, 2013).

16. Thomson’s Sells 7 Units in Chicago. Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Nov 1, 1956; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1989) pg. D9 (accessed November 23, 2013).

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid.

19. Historic Aerials map of Skokie Boulevard and Old Orchard Road, 1962 and 1974, http://www.historicaerials.com; (accessed October 18, 2013).

20. J. R. THOMPSON HEADS COMPANY FOR THIRD TIME: Paul Moore Resigns Restaurant Post. Forrester, Leland. Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Mar 19, 1941; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1989), pg. 29 (accessed November 10, 2013).

21. Henrici’s Cafe in Marl Is Being Modernized. Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Nov 23, 1947; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1989), pg. NA (accessed November 23, 2013).

22. Ibid.

23. A Lighting Effect for Every Mood, Henrici’s Restaurant, Merchandise Mart, Chicago. Architectural Record, July 1948, pg. 129-131.

24. Remodeled Restaurant and Bar in Chicago. Architectural Record, January 1940, pg. 100-102.

25. Ibid.

26. Younker to Remodel His North Side Restaurant. Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); May 25, 1941; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1989), pg. A10 (accessed November 10, 2013).

- Sharply Defined Masses: The Forgotten Work of James F. Eppenstein, Part 3

- Bertrand Goldberg in Tower Town Part 3: Bertrand Goldberg’s Michigan Avenue Project

- Good Modern: The Forgotten Work of James F. Eppenstein, Part 1

- Bertrand Goldberg in Tower Town Part 2: Postwar Development of Michigan & Pearson

- Chicago’s Shoreline Motels – South