Courtesy of Jacob Kaplan

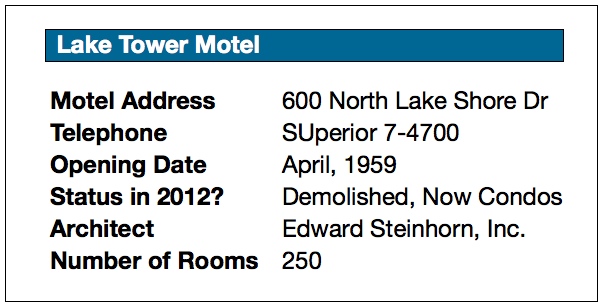

In this undated postcard, Lake Michigan and North Lake Shore Drive are seen two floors below the pool deck of the Lake Tower Motel. The Lake Tower opened in 1959 and would be demolished less than 30 years later;1 this lot would then remain vacant for more than 15 years until construction began on a condominium project in 2005.2

The Lake Tower was one of three Shoreline Motels to be built in central Chicago, from Ontario Street to the north and 13th Street to the south, all either facing Lake Michigan, or across from or near a lakefront park. All three of the motels discussed in this article, along with eight of the other 10 Shoreline Motels built on Chicago’s North and South sides, have since have been demolished. These motels comprise one of the shortest-lived and least studied styles of accommodations in the city; the motels in the central area are are listed below from north to south.

With one exception noted below, some 25 years passed with no significant new transient accommodations of any kind built in Chicago until the city’s motel, and later hotel, boom began in 1955, as examined here. Many of Chicago’s existing hotels, especially those in and around the Loop were rapidly aging, and were initially designed around travelers arriving by train and staying in the central area. By contrast, the new Shoreline Motels built starting in the 1950s were primarily designed for visitors arriving by and traveling around Chicago by car, and highlighted free parking for guests in their marketing.

Left: Chuckman Collection Right: Chicago History in Postcards

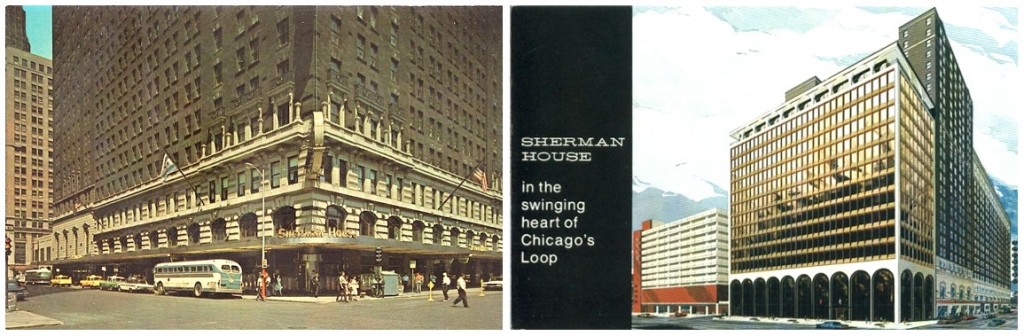

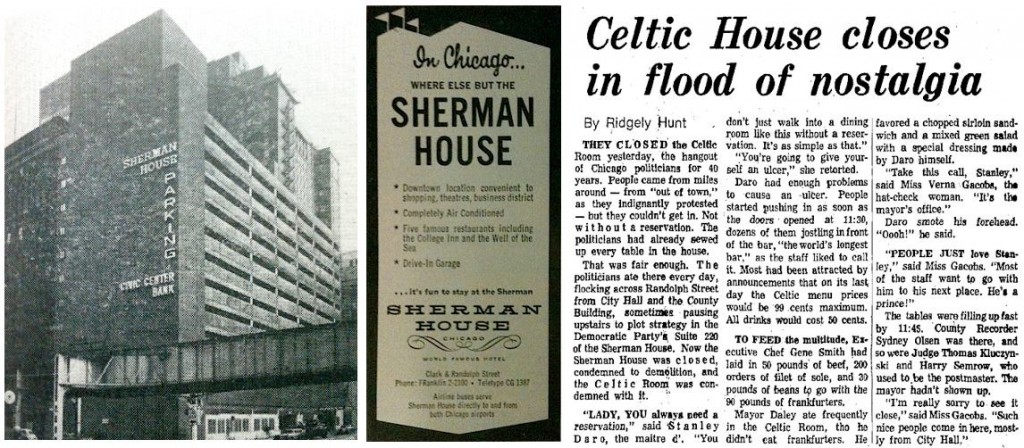

As with many aging Loop hotels, the enormous Sherman House Hotel was struggling by the 1950s and 60s. The Sherman House may have been “in the swinging heart of Chicago’s Loop”, but high taxes and maintenance costs, low occupancy rates, and rooms and amenities more suited to travelers from decades earlier all spelled doom for this once-iconic hotel.

Left: Realty & Building Center: Chain Store Age ad, 1963 Right: Chicago Tribune

The long decline and eventual demise of the Sherman House Hotel would ironically be repeated for all three of the central Shoreline Motels constructed in the 1950s and 1960s described below. In 1967, a Sherman House addition was completed featuring new exhibition space and a paid parking garage at the southeast corner of LaSalle and Lake Streets3 (shown above left), but this hotel continued to struggle, with the hotel portion closing just six years later on January 24, 1973.4

The Celtic Room, a popular political hangout for decades, closed nine days later, on February 2.5 After sitting vacant for the remainder of the decade, the Sherman House, along with this entire block, was demolished in the 1980s for the State of Illinois Center (now James R. Thompson Center), which opened in 1985.

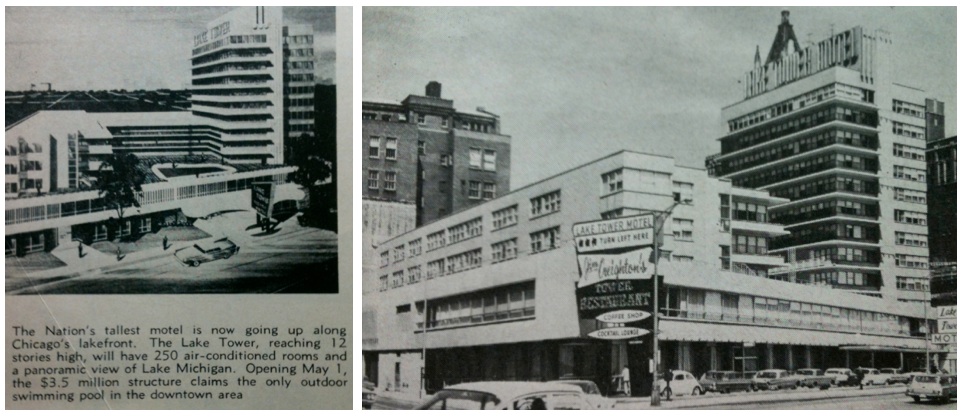

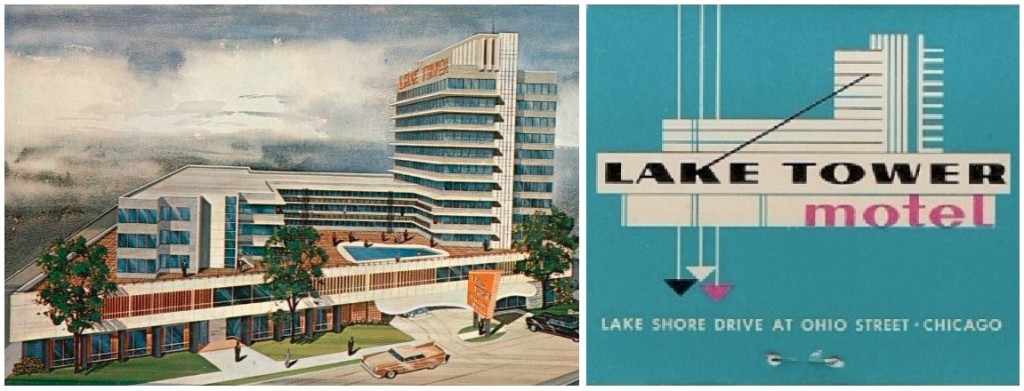

By nearly all definitions a building type that would be classified then and now as a hotel, the Lake Tower was specifically referred to as a motel prior to and for several years after its opening. Noted as “the Nation’s (sic) tallest motel” in the article below left, the Lake Tower also featured a prominent neon “MOTEL” sign affixed to the top of the building, seen in the image below right.

Left: Commerce, February 1959 Right: Realty & Building

The Lake Tower was Chicago’s only Shoreline Motel to exceed four stories; the word motel may have been chosen to convey modernity, and to avoid association with Chicago’s rapidly aging existing hotels such as the Sherman House. The Lake Tower also featured a unique amenity for central Chicago at the time of its completion – an outdoor swimming pool.

Courtesy of Jacob Kaplan

Not all of the Lake Tower’s rooms faced Lake Michigan, and views in the 1950s and 1960s of nearby aging commercial buildings were probably not what most visitors dreamed of seeing during a Chicago visit. Seen above are portions of two postcards printed around the same time and featuring the same photograph, but with a significant difference – the version on the left has the Lake Tower’s neighbors removed and replaced with a flat blue background. With the exception of the postcard above right, all other Lake Tower promotional images found for this article ignore the neighboring buildings.

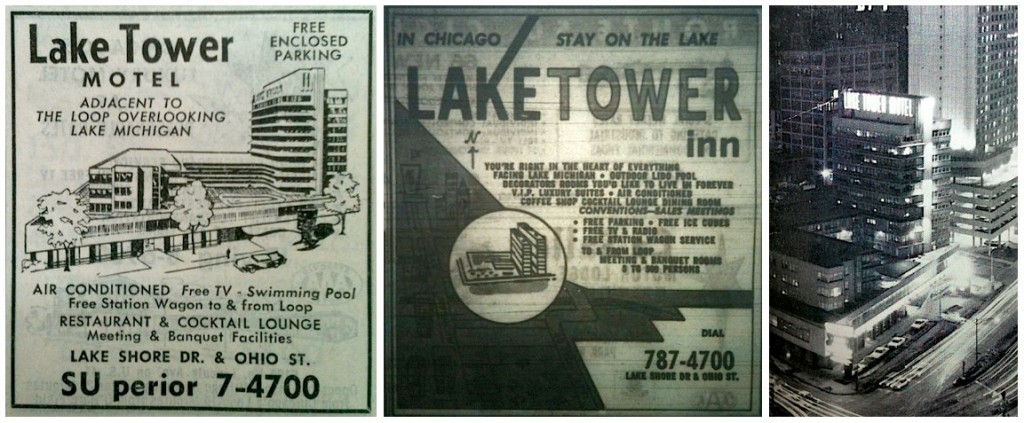

Top: Chuckman Collection Bottom left: 1959 Illinois Bell Classified Telephone Directory Bottom center: 1971 Illinois Bell Classified Telephone Directory Bottom right: Realty & Building

In later years, the Lake Tower would lose the “Motel” moniker and instead use “Inn” (above center). Still later it become the “Lake Shore Hotel”. Located on a lakefront lot, the relatively modest size of the Lake Tower would become an economic disadvantage in later years.

There were proposals at least as early as the mid-1980s to demolish the Lake Tower to build a much larger structure. An example of nearby denser lakefront development may be seen in the image at far right, with the lower portion of the 1965 Holiday Inn Lake Shore Drive towering one block north, which was completed just six years after the Lake Tower.

Realty & Building

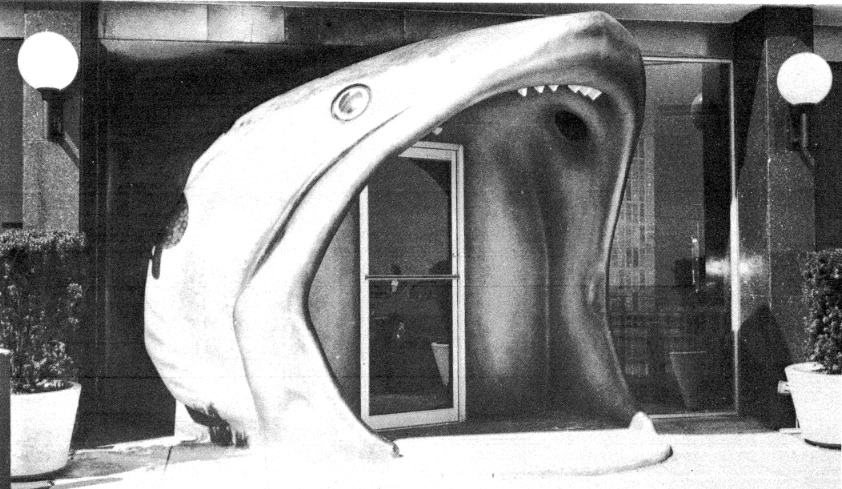

Perhaps capitalizing on “Jaws” mania, by 1976 the former Lake Tower, since 1975 a part of the Howard Johnson’s chain,6 would feature a plaster fish head at the entrance of its new Coho Lounge. Complete with teeth, this image was featured in a trade advertisement for the Chicago Plastering Institute soon after its completion. It is not known if the eyes of this oversized salmon lit up at night.

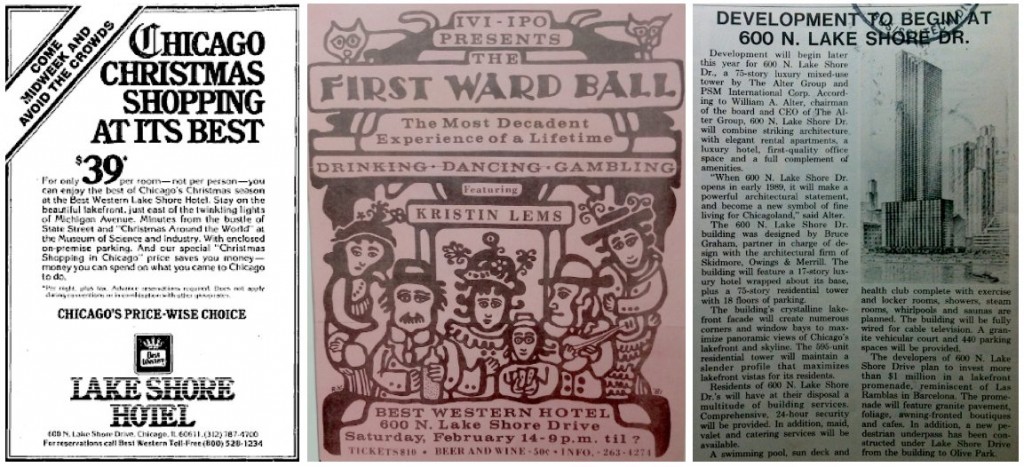

The affiliation of this motel would later change again, becoming a Best Western (below left). As was the case with many other Shoreline Motels, the value of the land underneath the building, as well as property taxes, had increased substantially by the mid-1980s, leading to increasing pressure for a denser and taller development.

Left: Chicago Tribune Center: IVI-IPO Right: Realty & Building

Realty & Building |

Less is known about the former Lake Tower towards the end of its operation, and the exact date this Shoreline Motel closed remains unknown; the property would disappear from aerial views by 1988.7 Seen above left is a 1983 ad for the Lake Tower, by now renamed the Best Western Lake Shore Hotel. Above center is a flyer promoting the Independent Voters of Illinois – Independent Precinct Organization’s 1981 annual First Ward Ball, held at this hotel.

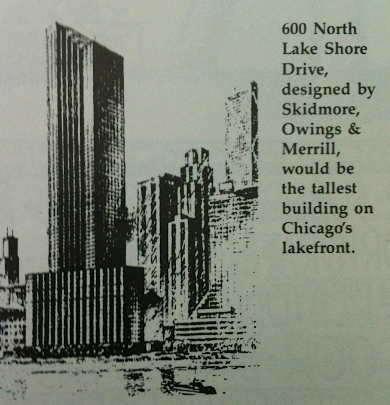

An ambitious and never-built proposal for the tallest building to be constructed up to that point directly facing Lake Michigan appears to have led to the former Lake Tower’s demolition. This project was designed by Bruce Graham of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and was originally designed as 79 stories, including a 17-story luxury hotel.8

Strong neighborhood opposition led this massive project to be scaled down from 789 to 699 feet; this revised plan was then approved by a 9-2 vote by the Chicago Planning Commission in November 1985.9 Despite assurances that construction of this building was imminent in October 1986 (above right), the project stalled. More than twenty years later, in 2009, two condominium towers of different heights were finally completed on this site.10

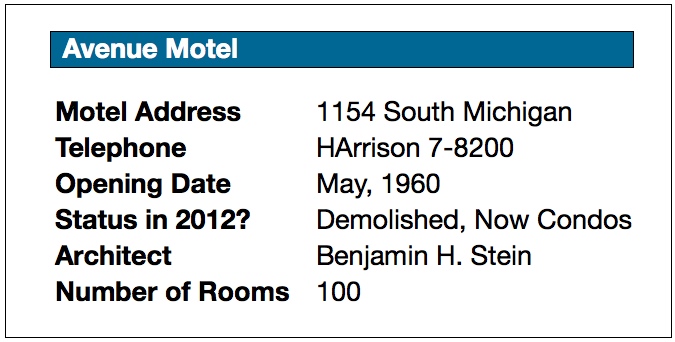

The Avenue Motel was a a modest motel with a commanding presence at the northwest corner of Michigan Avenue and Roosevelt Road. The only Shoreline Motel built facing Grant Park, the Avenue has long since been demolished and replaced (along with the other two central shoreline motels) with a condominium tower.

Chicago Tribune

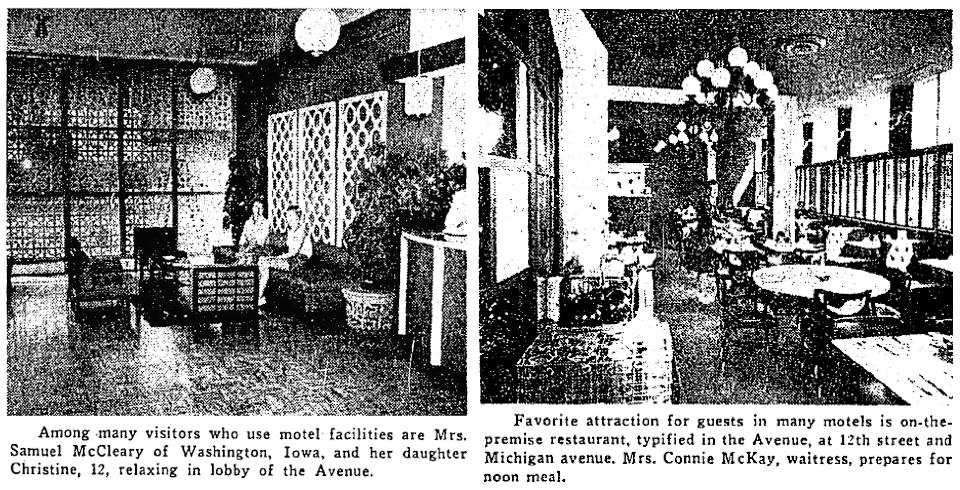

High-resolution interior photographs of the Avenue Motel have proven hard to find as of this writing. Published in August 1960, three months after opening, seen above are two rare views of this motel’s interior – the lobby and restaurant.

The photo below right taken on August 26, 1963 shows the Roosevelt Road elevation of the Avenue Motel along with the CTA elevated tracks and the Roosevelt Road station. The large parking sign does not appear in the postcard rendering above; it is not known if this rather prominent sign was added after the motel opened, or was airbrushed out of the postcard.

James S. Parker Collection, University of Illinois at Chicago. Courtesy Chicagopast |

The Avenue Motel also has a unique distinction as the site of a virtually unknown meeting of great historic significance in mid-twentieth century American politics, far less known than the crucial role Chicago and Illinois has played in the last sixty years selecting presidential nominees. Chicago hosted Democratic National Conventions in 1952, 1956, 1968 and 1996, with Democratic presidential nominees hailing from the Chicago area in 1952, 1956, and, of course, in 2008 and 2012. Chicago also hosted Republican National Conventions in 1952 and 1960.

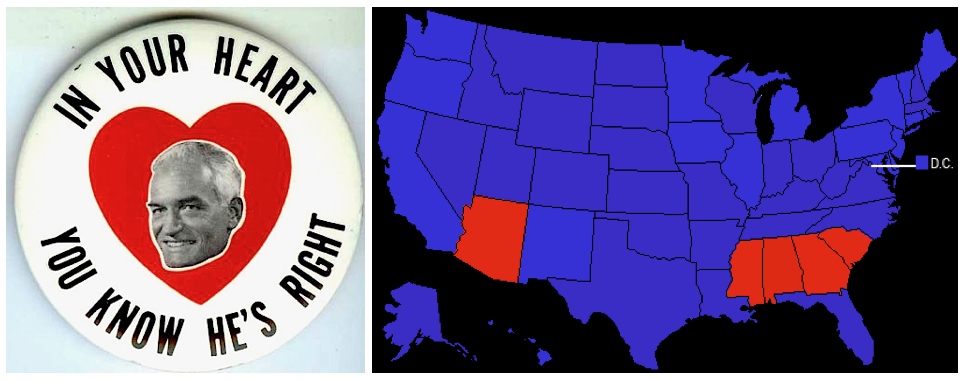

In his 2003 book, “Liberalism’s Last Hurrah: The Presidential Campaign of 1964” author Gary A. Donaldson describes a crucial meeting that occurred at the Avenue Motel more than three years before the 1964 presidential election. In his book, Donaldson writes, “But the nucleus of what would become the most significant of the draft-Goldwater movements grew our of a meeting on October 8, 1961 at the Avenue Motel on Michigan Avenue in Chicago.”11

Donaldson continues, “This meeting of some twenty-two conservatives was called by F. Clifton White, a one-time Cornell political science instructor turned political operator who has thrown his entire soul into the Republican party and the cause of American conservatism. To White, Goldwater was the very hope for the nation’s future.”12

Donaldson also writes, “The group decided to conceal their purpose, deciding even not to give themselves a name for fear of immediate repudiation. And they insisted, officially, that they had no candidate. This was to become, however, the Draft-Goldwater Committee.”13

Left: Will Rabbe Right: US Politics Guide

The ultimate result of the first Draft Goldwater meeting at the Avenue Motel, and his later nomination as the 1964 Republican presidential candidate, was a disaster. In that election, Goldwater received less than 39% of the vote, and lost such traditionally conservative states as Alaska, Wyoming, Utah, Idaho, North Dakota, South Dakota, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska. With the exception of Alaska, all of these states had voted Democratic in 1964 for the first time since the 1930s or 1940s.14 In the nearly half-century since Goldwater’s historic loss, none of these nine states has again voted Democratic for president.

Chicago Photographic Collection, University of Illinois at Chicago, no date

As had happened with the Sherman House and the other two central Chicago Shoreline Motels, the Avenue Motel would enter a period of decline. By late 1998, a variety of plans were being considered for the site, including everything from a jazz museum to a 10,000 square-foot art gallery mall.15 The main objective, however, seemed to be the removal of this building, now considered an eyesore along the gateway to the recently completed Museum Campus.16.

None of the arts-related venues would be built on the property; a high rise condominium was completed on the site in January 2008,17 including 6,500 square feet of retail space available on the building’s street level located midway between a Metra Electric District Line station and the CTA Red, Orange and Green Line stations.18 As of early 2013, more than five years since this building was completed, none of the retail space at the once-lively corner of Michigan and Roosevelt has yet been rented.19

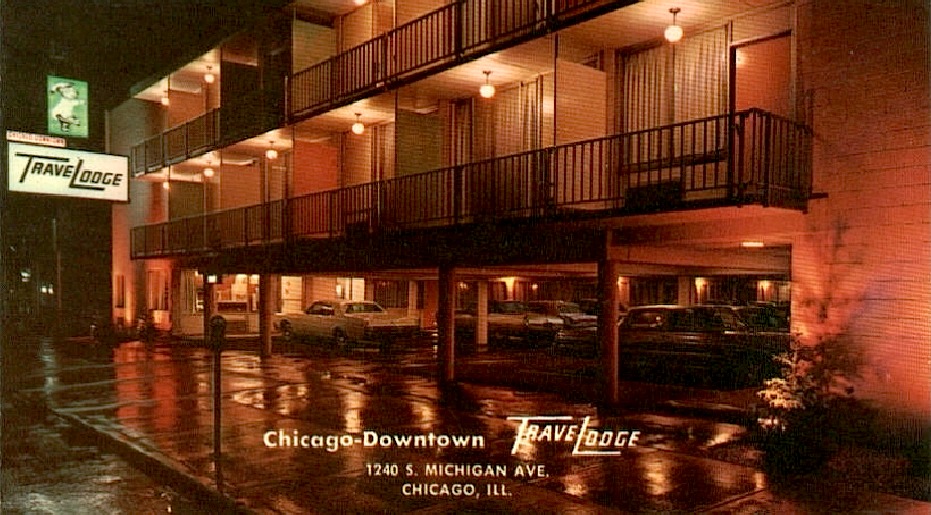

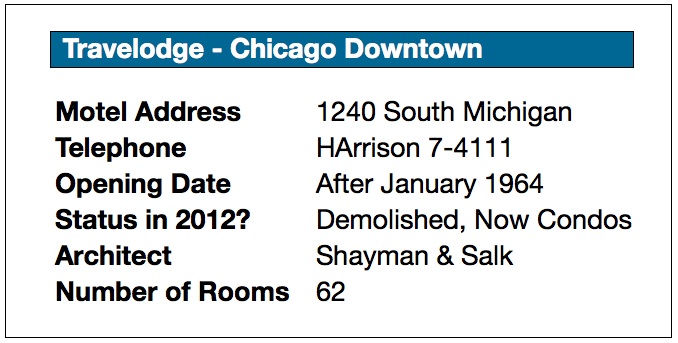

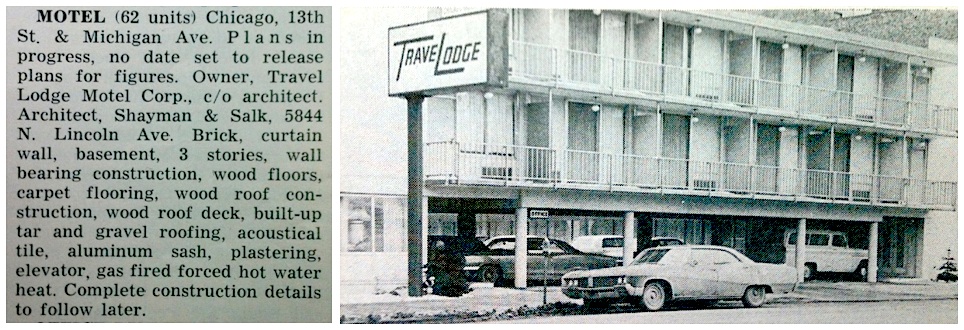

The Travelodge – Chicago Downtown was the last of the 13 Shoreline Motels to be built in Chicago, and was announced in January 1964 (below left).20 It is not clear when this hotel eventually opened. Its later history and the date it was demolished for the condominium project now at this site is unknown. At the time of its construction, the Travelodge was located near both Grant Park and the still-extant Central Station serving the Illinois Central Railroad, which would itself be demolished in 1974.

View north on South Michigan Ave. from 1240 So. Michigan Ave., 8/11/71, Sigmund J. Osty visual materials (Chicago History Museum), box 2

The Travelodge was a modest 62-unit property, with a manager’s apartment and parking for 52 cars.21 This motel was designed by architectural firm Shayman & Salk, who designed other Shoreline Motels examined in this series of Forgotten Chicago articles.

Realty & Building

Chicago Tribune, 1952 |

Preceding the opening of all the motels described in this article, the first new hotel in central Chicago in 22 years opened on June 14, 1952.22 Called in the article at right what “might almost be called Chicago’s first downtown motel,”23 it was actually a hotel as defined by its design and name.

The Town House had some “neat” features, such as a check-in desk in the basement parking garage and a lobby styled in the “fiesta mode” of Texas and the Southwest. The architect of the Town House is not known as of this writing, and the exterior, unlike most other Shoreline Motels, was utilitarian.

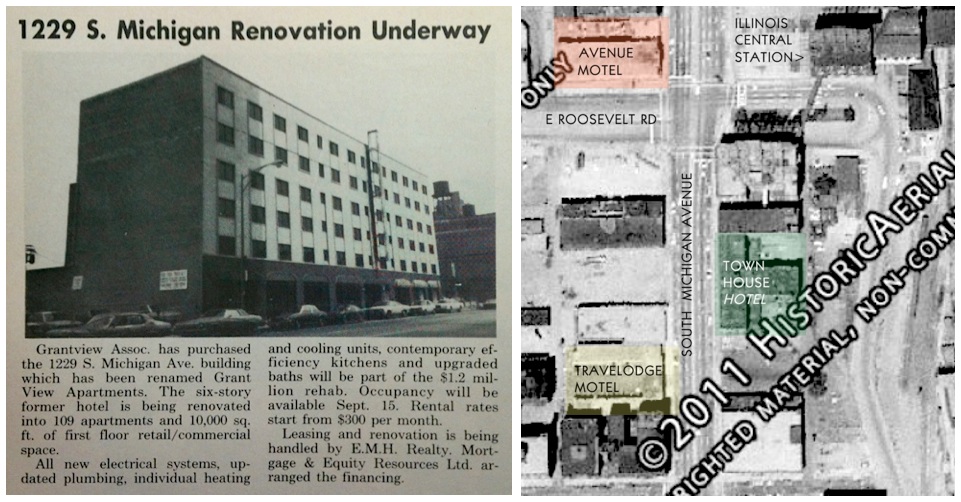

Little is known about the Town House in later years. Listed as a 50-room hotel in a travel guide to Chicago published in 1977,24 the property was sold at auction for just $500,000 in 1983,25 less than the cost of some condominiums in the area 20 years later. This property at the time of its sale in 1983 was described as a 111-unit apartment and commercial complex.26

Forgotten Chicago Archives

American Hotel Association’s Hotel Red Book 1955-1956

Exterior photographs of the Town House are also extremely rare. In the article below announcing a 1986 sale of this property, there appears to a disused vertical hotel sign with its letters removed.

Left: Realty & Building, 1986 Right: Forgotten Chicago map utilizing Historic Aerials from 1973

As described above, in August 1986 this building was sold again and renamed the Grant View Apartments.27 In September 1987, a 60′ by 40′ mural was dedicated on the blank wall seen above as a celebration of Chicago’s 150th birthday; painted by artist Romano Maschietto, the mural depicted scenes of bicyclists enjoying Chicago parks.28 As of this writing no images of this mural, likely the largest project commemorating Chicago’s sesquicentennial, have been found.

The Town House has since been demolished, and the majority of the site is currently a vacant lot. The map above right utilizes a 1973 aerial view and shows the footprints of the Town House Hotel, two nearby former Shoreline Motels and Illinois Central Station.

The next, and final, article in this series will explore Shoreline Motels in Hyde Park and South Shore.

1. Historic Aerials of East Ohio Street and North Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL, 1988; http://www.historicaerials.com (accessed December 5, 2012).

2. Emporis data on 600 North Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL; http://www.emporis.com/building/600-lake-shore-drive-south-tower-chicago-il-usa (accessed November 9, 2012).

3. Sale-Leaseback at LaSalle and Lake. Realty & Building, December 16, 1967, pg. 1.

4. ALVIN NAGELBERG. Sherman House closing to mark end of hotel era. Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file); Jan 15, 1973;

ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1988), pg. C9 (accessed December 19, 2012).

5. RIDGELY HUNT. Celtic House closes in flood of nostalgia. Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file); Feb 3, 1973; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1988), pg. 3 (accessed January 8, 2013).

6. Lake Tower Inn in Johnson Chain. Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Dec. 15, 1975; ProQuest Historical Newspapers Chicago Tribune (1849 – 1987) Section 6, pg. 8 (accessed November 30, 2013).

7. Historic Aerials of East Ohio Street and North Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL, 1988; http://www.historicaerials.com (accessed December 5, 2012).

8. JOHN MCCARRON. Skyscraper faces tough climb. Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Oct. 20, 1985; ProQuest Historical Newspapers Chicago Tribune (1849 – 1987) Section 2, pg. 1 (accessed January 10, 2013).

9. STANLEY ZIEMBA. Project a tall order, city warned. Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Nov. 26, 1986; ProQuest Historical Newspapers Chicago Tribune (1849 – 1987) Section 2, pg. 5 (accessed January 10, 2013).

10. Emporis data on 600 North Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL; http://www.emporis.com/building/600-lake-shore-drive-south-tower-chicago-il-usa (accessed November 9, 2012).

11. GARY JOHNSON, Liberalism’s Last Hurrah: The Presidential Campaign of 1964. By Gary A. Donaldson (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 2003), pg. 56.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. State presidential voting results 1936-2012; http://www.270towin.com/states/ (accessed February 1, 2013).

15. THOMAS CORFMAN. Developers vie for Cultural Campus gateway project. Crain’s Chicago Business, Nov. 30, 1998;

http://www.chicagobusiness.com/article/19981128/ISSUE01/10001892/developers-vie-for-cultural-campus-gateway-project#ixzz2KYjPQQS0 (accessed January 29, 2013).

16. Ibid.

17. Emporis data for The Columbian, 1180 South Michigan, http://www.emporis.com/building/the-columbian-chicago-il-usa (accessed November 5, 2012).

18. Ground floor retail listing for The Columbian. http://www.loopnet.com/Listing/16755085/1160-S-Michigan-Avenue-Chicago-IL/ (accessed February 3, 2013).

19. Ibid.

20. MOTEL (62 units), Chicago. Realty & Building, Jan. 18, 1964, og. 36.

21. Ibid.

22. New Central District Hotel Opens Today. Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Jun 14, 1952; ProQuest Historical Newspapers Chicago Tribune (1849 – 1987), pg. B5 (accessed February 7, 2013).

23. Ibid.

24. Flashmaps: The 1978-79 Instant Guide to Chicago (Chappaqua, New York: Flashmaps, Inc., 1977), pg. 20.

25. Michigan Ave. Building Sold at Auction. Realty & Building, Oct. 8, 1983, pg. 24.

26. Ibid.

27. 1229 S. Michigan Renovation Underway. Realty & Building, Aug. 9, 1986, pg. 12.

28. SHARON ROSE. Chicago gets a birthday card–and it’s big. Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file); Oct 8, 1987;

ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1989), pg. D17F (accessed January 30, 2013).

- The Miami of Canada: Chicago’s Shoreline Motels

- Beach Coats, Shoes, and Robes, Please: Shoreline Motel Ephemera

- Chicago’s Shoreline Motels – South

- Chicago’s Shoreline Motels – North

- Bertrand Goldberg in Tower Town Part 1: Bertrand Goldberg’s Commune