Sidewalk stamps can be found on the streets of American cities large and small. These ubiquitous inscriptions are the proud commemorations of a job well done, as well as a practical and long-term form of advertising. They are also explicitly required by law. Chicago’s Municipal Code states:1

Before the top or finishing of concrete walks has set, the contractor or person building the walk shall place in such walk in front of each lot or parcel of property a stamp or plate giving the name and address of the contractor or person building the walk and the year in which the work was done. The top of said plate or stamp, which must not cover more than 54 square inches of surface, shall be flush and even with the top of the finished walk, and must be of a permanent character plainly stamped or firmly bedded in the concrete in such a manner that it cannot become loose or be easily removed or defaced.

Wherever one contractor or person has laid walks in front of three or more adjoining lots or parcels of property in one continuous stretch, one of the above named stamps placed in the walk at each end of said stretch of walk will be sufficient.

There are two different types, stamps and plaques, and they serve two purposes — identification and advertisement. The most common type of sidewalk marker is stamped into newly poured concrete and becomes an indelible feature of the sidewalk, sharing the same space as children’s footprints and lovers’ inscriptions. The less common form is a pre-cast brass plaque which is set into wet concrete. These are not “stamps” as such, although they are used in the same ways. Stamps most often bear the name of the construction firm that laid the sidewalk and the year the work was done. Additional information can include the company’s location and telephone number. Less commonly, a stamp will carry broader information such as the name of a subdivision and its developer.

This page is a short survey of sidewalk stamps in Chicago, not an exhaustive list. There are a number of websites on the topic, see here, here, and here. There is also a dedicated flickr group, and some can also be found in our own flickr group.

Left: Matthew Kaplan

Left: Matthew Kaplan

Stamps and plaques are “permanent” in different ways. Stamps are literally part of the sidewalk and are very rarely filled in or removed. However, they are easily and often lost when a portion of sidewalk is reconstructed. There are rare examples where an old stamp is integrated into a new sidewalk, but this is an exceptional occurrence. Brass plaques can be more easily removed from a sidewalk, although they are also most often removed when the sidewalk is reconstructed. They do have a better chance at surviving as individual artifacts.

The 1904 Young & Olmsted plaque is the oldest we’ve found in Chicago as of this writing. It is located on a residential street in Rogers Park and is in excellent shape for being 106 years old. This is likely due to the fact that it has seen considerably less foot traffic than a sidewalk in a commercial district, one of a number of circumstances in which a stamp or plaque can survive for a long time. The “City” inscription above the plaque remains a mystery. The Hoeffer stamp is located on Winona Street in Uptown, under the L embankment — another favorable location for survival.

Beyond the obvious point that stamps from a given year or decade become more scarce as they age, some are more difficult to find than others. Much of the road and sidewalk construction in the 1930s was done under the Works Progress Administration. Although WPA stamps exist elsewhere in the country, they are difficult to find in Chicago. Private companies are responsible for the bulk of sidewalk stamps. Due to the downturn in private construction during the 1930s, stamps from this decade are fairly rare.

The typeface of stamps is usually an easily legible, utilitarian sans-serif. This serves a practical purpose in that the stamp will remain legible as it undergoes wear. Decoration is generally reserved for the border (if there is a border at all), which is most often rectangular or ovular. Deviations from sans-serif typefaces and rectangular or ovular borders constitute an aesthetic consideration above and beyond the norm. The above stamps are examples of interesting variations. A serif typeface is creatively deployed on the Rodman stamp, and the border of the Cement King stamp takes the form of a crown — a clever reinforcement of the company’s name.

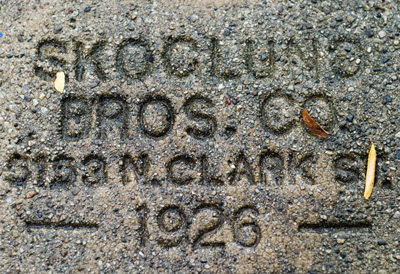

Stamps can reflect changes in the name and location of a company. In 1926, Skoglund Brothers Co. was located at 5153 N. Clark Street. By 1975 the company was called A.H. Skoglund Co. and was located at 8800 Center Avenue, a residence in suburban River Grove. This indicates that Skoglund was likely a small, family business passed down from one generation to the next in the midst of outward migration to the suburbs.

Both the Skoglund and Thomas stamps seen above have been removed since these photographs were made. The Skoglund stamp was on a residential street off of Taylor street and was removed when the sidewalk was reconstructed less than a week after we spotted it. The Thomas stamp was located in front of the Dreyfus Research Pavilion on the Michael Reese campus, and we all know how that went.

The vast majority of stamps convey information in a straightforward way. The above two examples are a bit more mysterious, especially the brass “13.” Located on Federal Street alongside the Monadnock Building, it is most likely a pre-1911 address. It could also indicate that the sidewalk was laid in 1913. Without additional information to contextualize it, and owing to the fact that the circular patch of concrete surrounding the marker is different than the rest of the sidewalk, its meaning remains ambiguous.

The undated clover-shaped Simpson brass plaque does well at indicating the ethnic identity of the company, but is confusing otherwise. Located on Morse Avenue east of Sheridan, it is undated and reads “Trademark Reg.- Laid by Simpson Bros. – Chamber of Commerce – Chicago.” Was Simpson a contractor, or the developer of this area? Which Chamber of Commerce was involved, and to what extent?

Perhaps the more mysterious a stamp is, the less it conforms to the usual use of such markers, the more interesting it becomes to posterity. Otherwise, sidewalk stamps remain as miniature tributes to the multitude of small businessmen and laborers who literally made this city.

- Expressway Parks

- Lake Shore Drive Redux

- South Western Avenue Improvement

- St. Ignatius Architecture Graveyard

- Bridge Out For Good