Look around when you’re out and about Chicago. Check out industrial buildings. Look at basement windows, look at bathroom windows. It’s hard to miss glass block. This ubiquitous architectural detail got me wondering: where did it all come from? Is Chicago unique in its use (possibly abuse) of glass block? And how did we get this way?

Joe Sislow

Sometimes glass block is artistic and inspired, sometimes glass block is an example of an era, and sometimes it’s just…wrong. Glass block — or glass brick — has an interesting history and connection to Chicago that leads through multiple companies and two Chicago world’s fairs. This Chicago related history of glass block is split into two parts. The first part covers the pre-history of glass block, including many of its predecessors. The second part will cover glass block proper and its rise in Chicago.

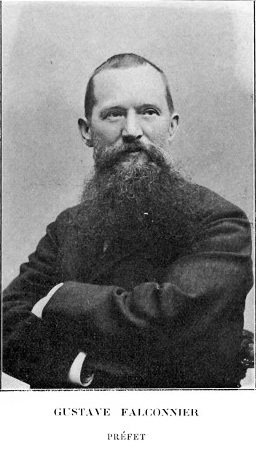

The 1893 Columbian Exposition is known for introducing many things to the United States. One lesser known first: the Exposition showed the United States the first glass bricks…by one Gustave Falconnier. Falconnier — an architect, city council member, prefect of Nyon, France, and a graduate of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris — had many patents in the 1880s for various types of glass block of interesting geometric shapes.

The 1893 Columbian Exposition is known for introducing many things to the United States. One lesser known first: the Exposition showed the United States the first glass bricks…by one Gustave Falconnier. Falconnier — an architect, city council member, prefect of Nyon, France, and a graduate of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris — had many patents in the 1880s for various types of glass block of interesting geometric shapes.

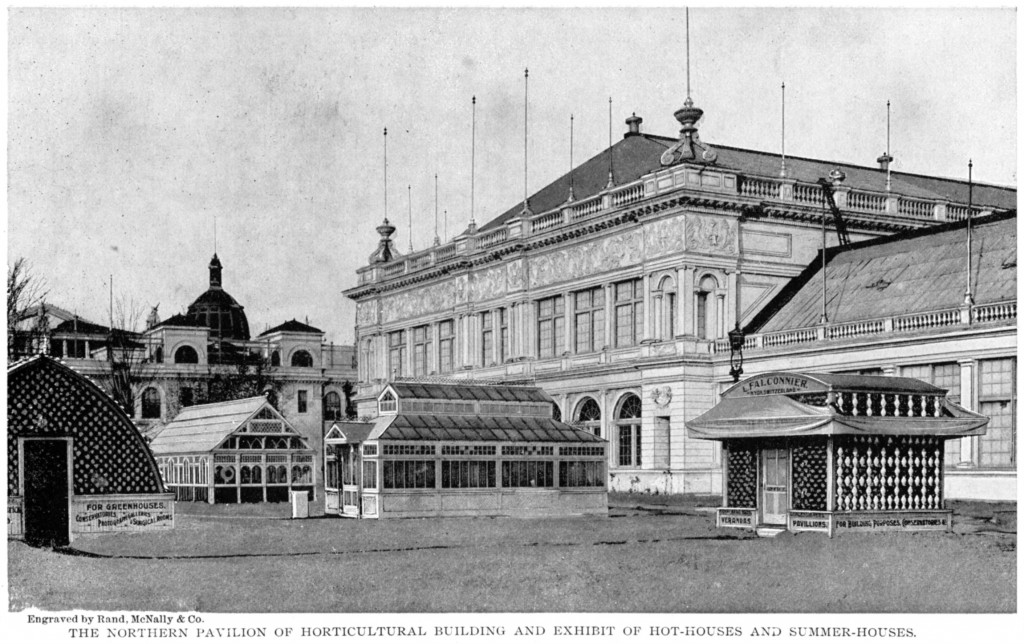

At the 1893 Columbian Exposition, Falconnier exhibited his glass in buildings outside of the Horticultural Building, showing their potential uses in architecture and horticulture. Falconnier was given an award by the fair commission for, “a new departure in glass building.” Despite being shown in the horticultural pavilion, the commission gave him a somewhat backhanded award, saying that, “Their adaptability for conservatories intended for plant cultivation has not yet been fully demonstrated, but for conservatory vestibules and other rural effects they are well adapted.” And finally, “In the construction of surgical, photographic, and other experimental laboratories, where extra subdued light is required, they possess great merit.”1

Despite the awards, Falconnier’s glass block had a flaw that prevented it from ever taking hold in America. Because they were blown glass, the blocks needed a hole. Even a small hole, eventually plugged up, can lead to fogging. Once fogged, the bricks would need to be replaced. A tall order indeed for something that is meant to be permanently put into a wall.

Glass block would take a second try at a world’s fair before it really took hold in US architecture. However, other types of architectural glass that would be formative to glass block’s future were taking shape in Chicago.

Rand McNally, courtesy of glassian.org

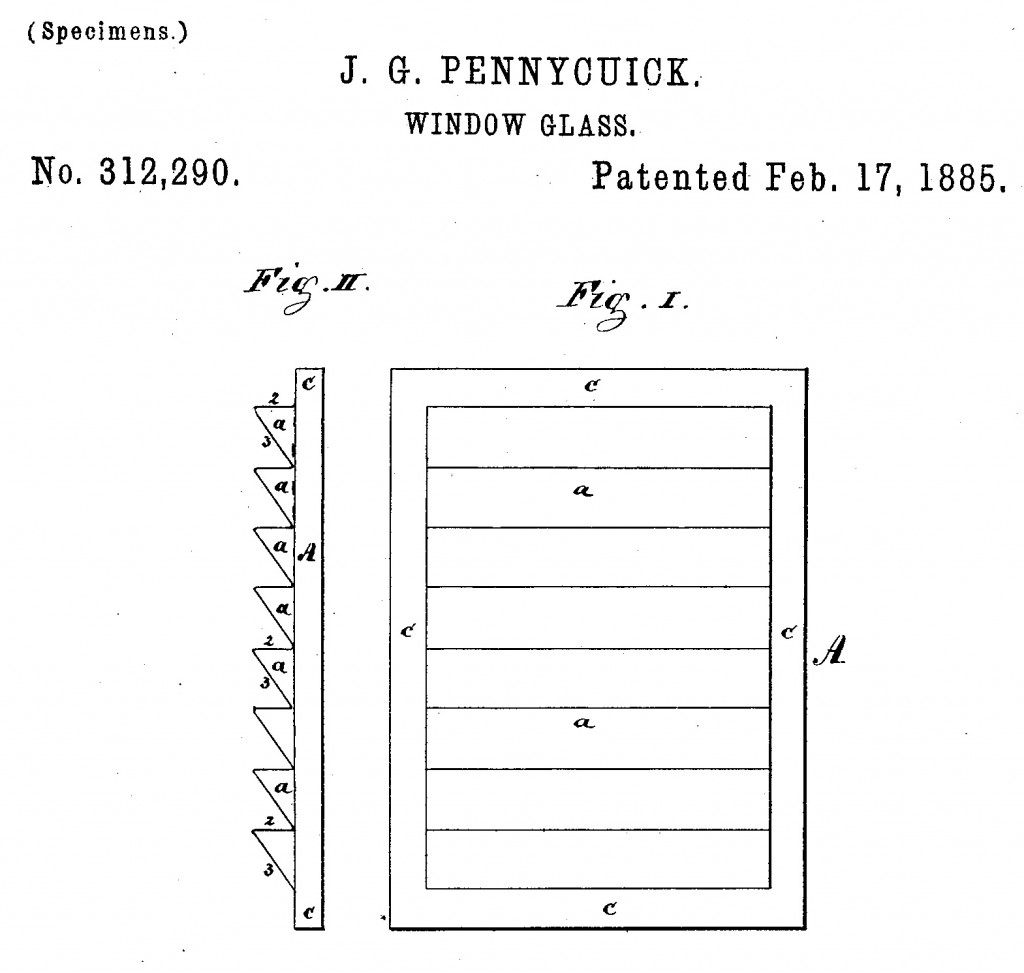

Falconnier’s first patents were filed in 1886. But in 1882 in the US, James G. Pennycuick filed a patent for a type of glass “whereby the reflection of the light into the room is considerably increased without increasing the size of the window.” His patent continued, “by this construction of window-glass about double the quantity of reflection or illumination of the plain window-glass of same size will be obtained, and will obviate the necessity of ground or opaque glass (whereby the admission of light is still more obstructed) in places where it is desirable to have a view into the room from the outside.” He followed, “I am aware that it is not broadly new to provide window-glass with reflecting ridges.”2

This style of glass started with deck prisms. Ship builders had to solve the problem of how to get light below deck during long voyages. Prisms were set flush with the deck of the ship, and when sunlight hit the deck, it was efficiently transferred below to light up the cabins.

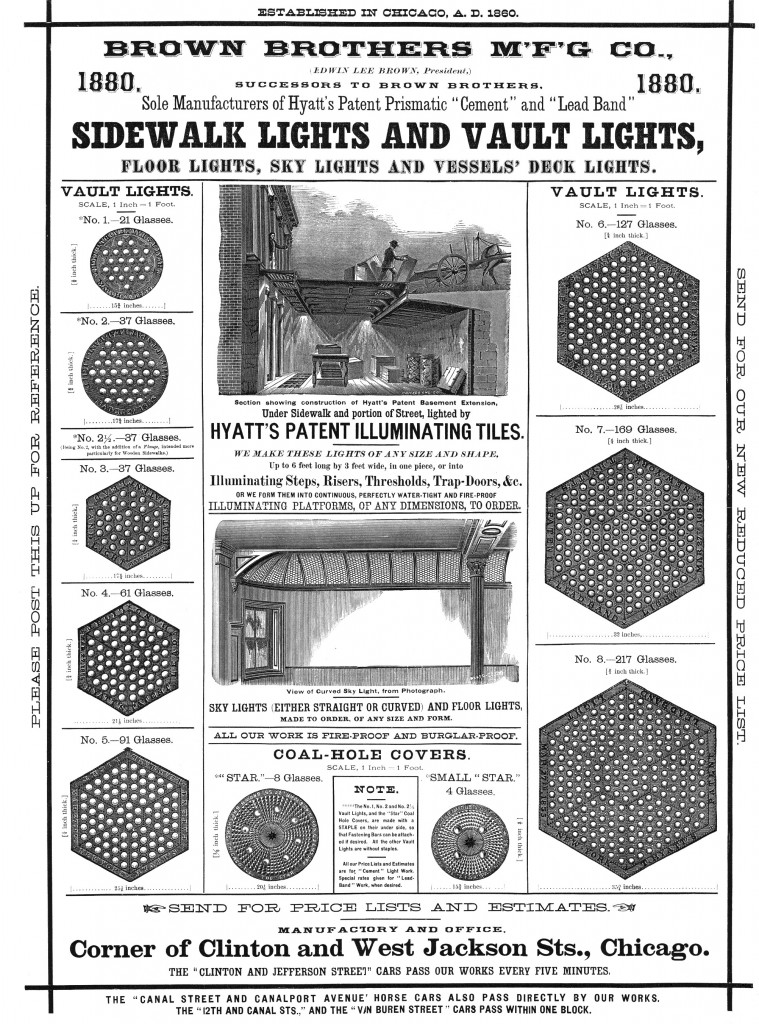

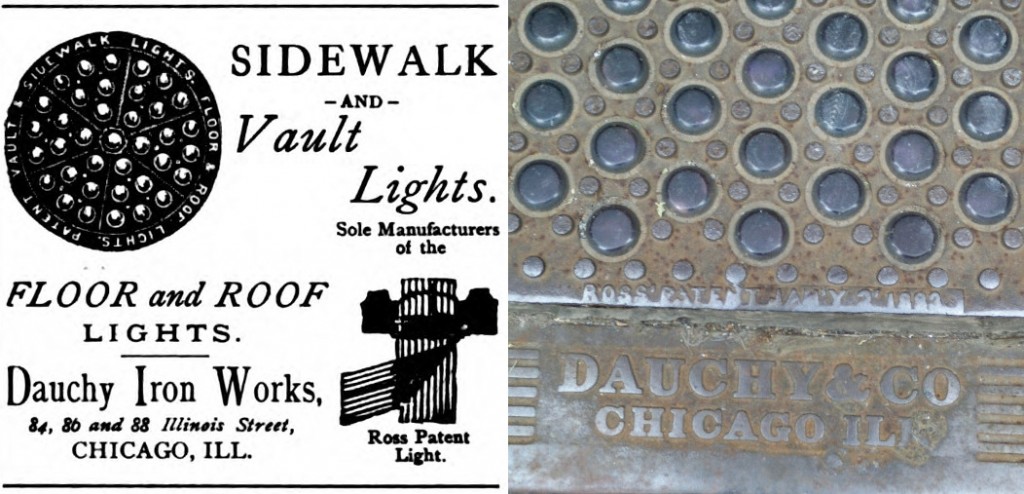

This concept was applied to rooms and areas below sidewalks and entryways. Deck prisms became vault lights. They were used in much the same way deck prisms were used: by setting prism glass objects in the sidewalk or stoops, light could be transferred from outside without the need for grates or windows.

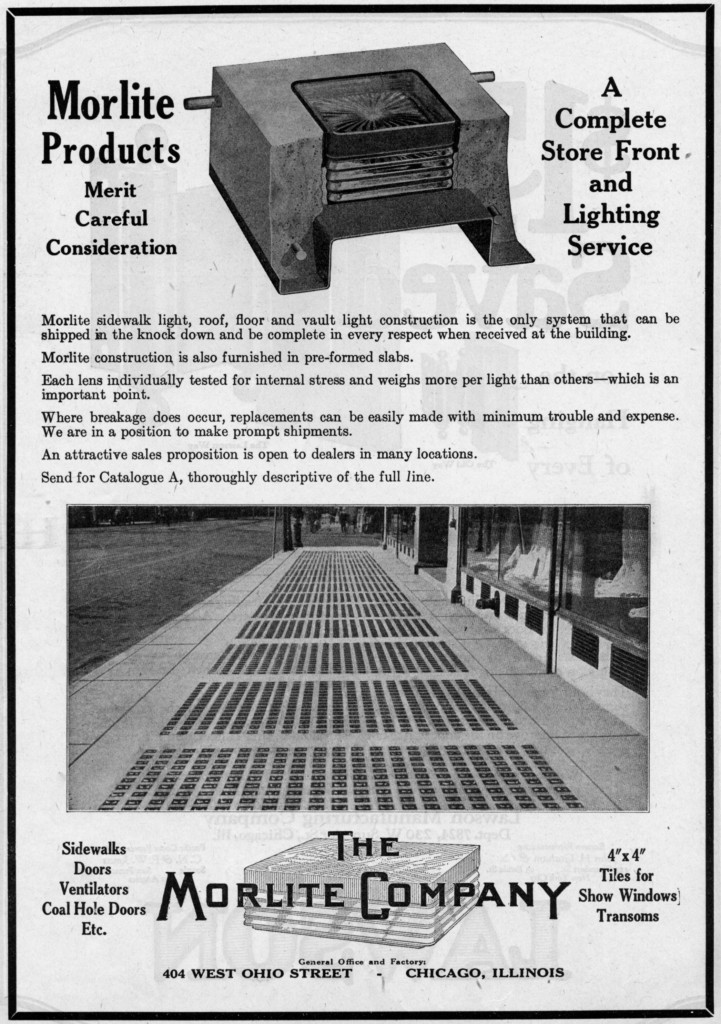

Many Chicago companies manufactured vault lights, leveraging Chicago’s manufacturing strengths. Chicago never adopted vault glass the way other cities did, but our companies contributed heavily to its adoption around the country.

American Builder, 1921

As cities looked for more ways to expand in high demand downtown areas, such subterranean rooms were common. Chicago, like other cities with large downtown populations, was no exception. Unfortunately, in cities like Chicago, sidewalks are regularly redone, so evidence of such lights can be hard to find. Thankfully, a few examples are still extant in Chicago on Printer’s Row.

Left: Inland Architect Right: Joe Sislow

In August of 1882, James Pennycuick filed for the aforementioned patent. In February of 1885, his patent was granted. He made several attempts to start companies to capitalize on this technology. In 1895, he had entered a partnership with Thomas W. Horn and founded the Prismatic Glass Company in Toronto, Canada. There were still problems in making the glass tiles into sheets, and the company was unsuccessful. However, he met one William Winslow, a Chicagoan who invented an electro-glazing process using thin copper strips and an electrolytic bath to form the tiles into strong, seamless panels that are seamless and light.3

In August of 1882, James Pennycuick filed for the aforementioned patent. In February of 1885, his patent was granted. He made several attempts to start companies to capitalize on this technology. In 1895, he had entered a partnership with Thomas W. Horn and founded the Prismatic Glass Company in Toronto, Canada. There were still problems in making the glass tiles into sheets, and the company was unsuccessful. However, he met one William Winslow, a Chicagoan who invented an electro-glazing process using thin copper strips and an electrolytic bath to form the tiles into strong, seamless panels that are seamless and light.3

In 1896, Pennycuick founded the Radiating Light Company in Chicago to capitalize on the process. Winslow introduced Pennycuick and Horn to a number of prominent Chicagoans who eventually invested in the company.4 The investors and collaborators are a who’s who of Chicagoans: Cyrus McCormick (president of McCormick Harvesting Machine Company), Edward C. Waller (prominent real estate developer), George A. Fuller (architect, president of George A. Fuller Company, builder of Rookery, Monadnock, and heavily involved in the building of the 1893 World’s Fair), Charles H. Wacker (director of 1893 World’s Fair, brewer, and eventual Chairman of the Chicago Plan Commission), Levi Z. Leiter (co-founder of Marshall Field & Co), and eventual president of Pennycuick’s company Jon Meiggs Ewen (engineer & GM for Burnham & Root, and partner with George Fuller). Later that year the company was renamed the Semi-Prism Glass Company, and in 1897 it became the Luxfer Prism Company.

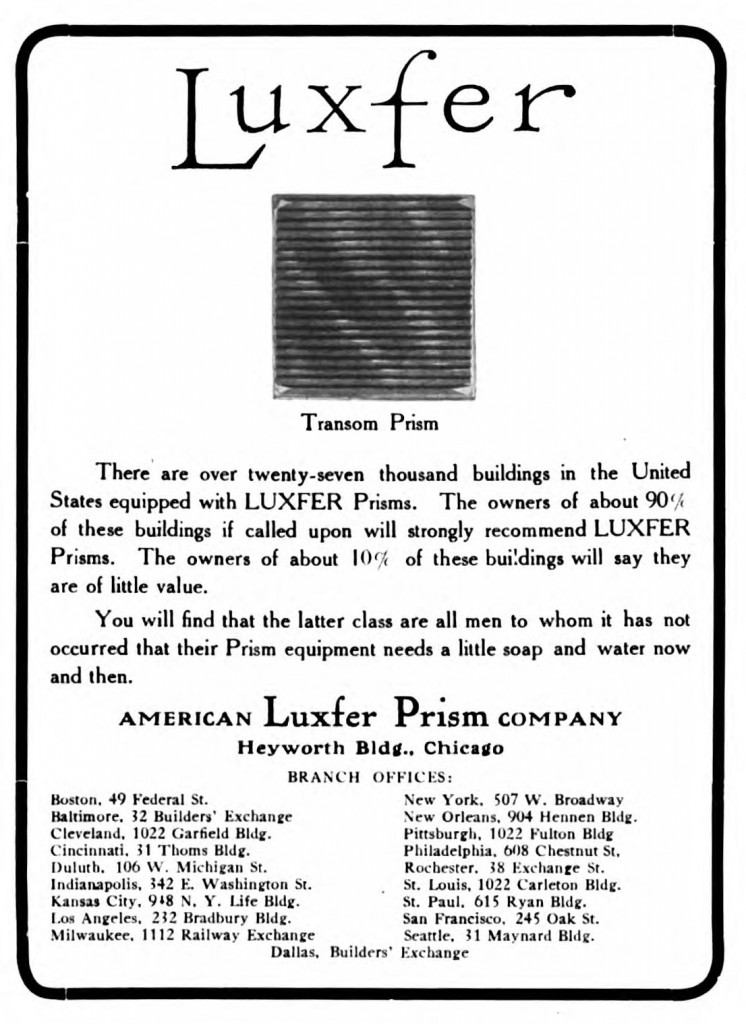

With all of the investment and attention, the company took off. The company advertised widely and gained accolades from the architectural field. The company hired two Northwestern physics professors, Henry Crew and Olin H. Basquin, to work on optimizing the performance of the tiles in gathering light. In their book, Pocket Hand-Book of Useful Information and Tables Relating to the Use of Electro-Glazed Luxfer Prisms, the two physicists described installations that would be incredible today. The panes have various angles that can direct light, and they can be installed in windows or in awning like installations.5

With all of the investment and attention, the company took off. The company advertised widely and gained accolades from the architectural field. The company hired two Northwestern physics professors, Henry Crew and Olin H. Basquin, to work on optimizing the performance of the tiles in gathering light. In their book, Pocket Hand-Book of Useful Information and Tables Relating to the Use of Electro-Glazed Luxfer Prisms, the two physicists described installations that would be incredible today. The panes have various angles that can direct light, and they can be installed in windows or in awning like installations.5

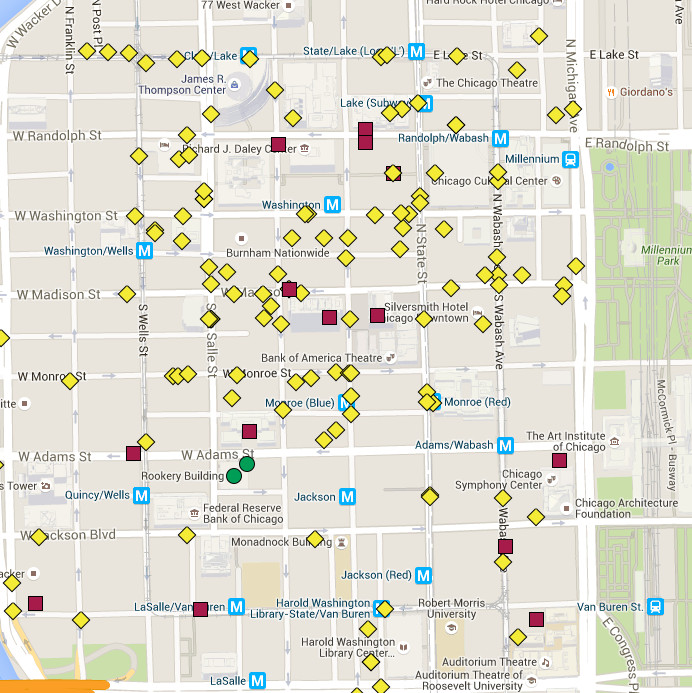

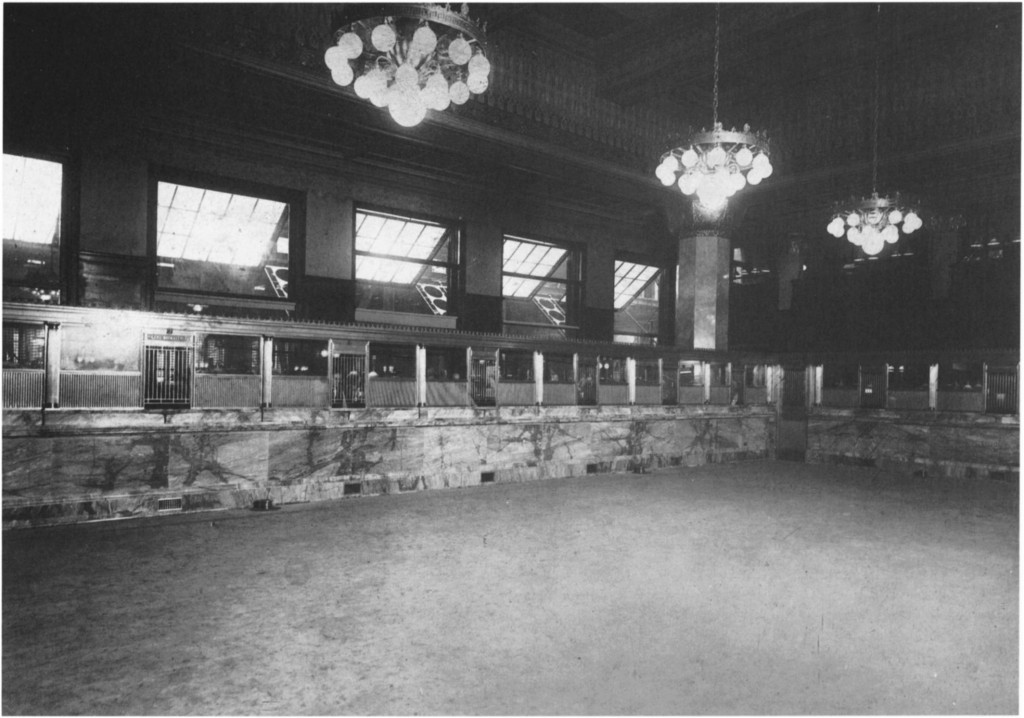

By the end of 1898, the American Luxfer Prism Company had offices in 12 cities, completed 1800 contracts, and placed $700,000 worth of product in buildings around the country. An ad from The Economist that year listed over 130 installations in 16 different cities. Chicago had 28 locations alone. In the Pocket Hand-Book, 183 buildings in Chicago with prism glass are listed, and some of the buildings were as noteworthy as the Rookery, the Manhattan Building, The Schoenhofen Brewing Company, the Bank of Montreal (BMO/Harris today), the Chicago Stock Exchange, Marshall Field & Company, the Montauk, and the Union League Club.6

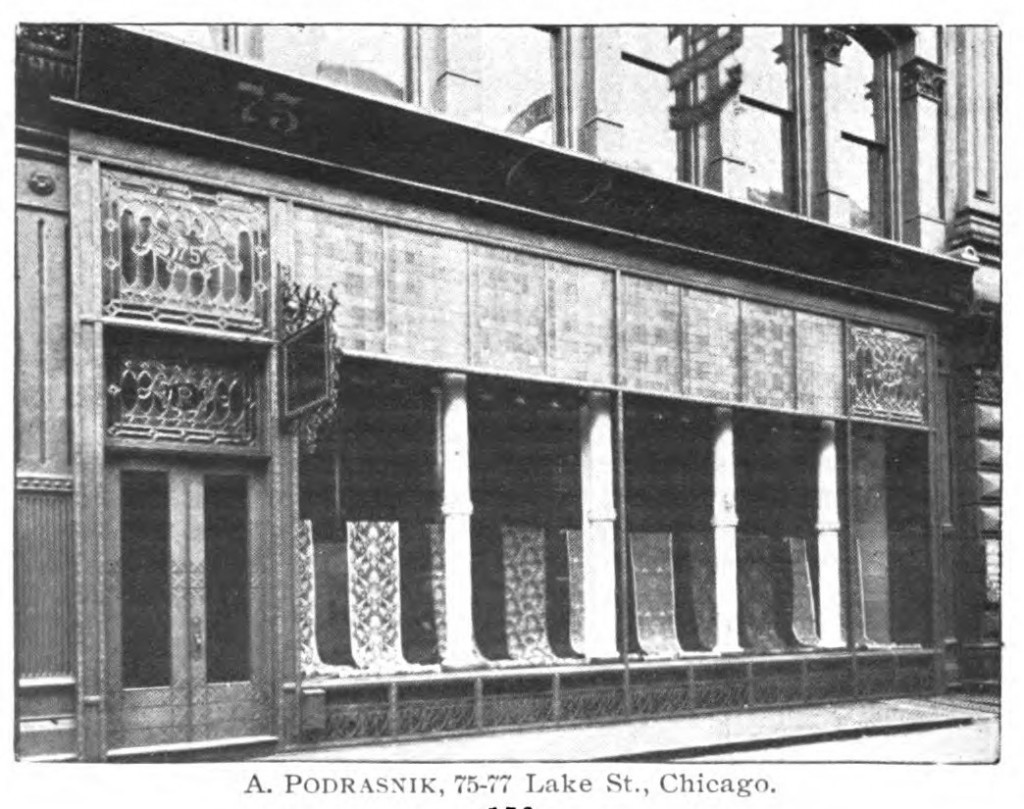

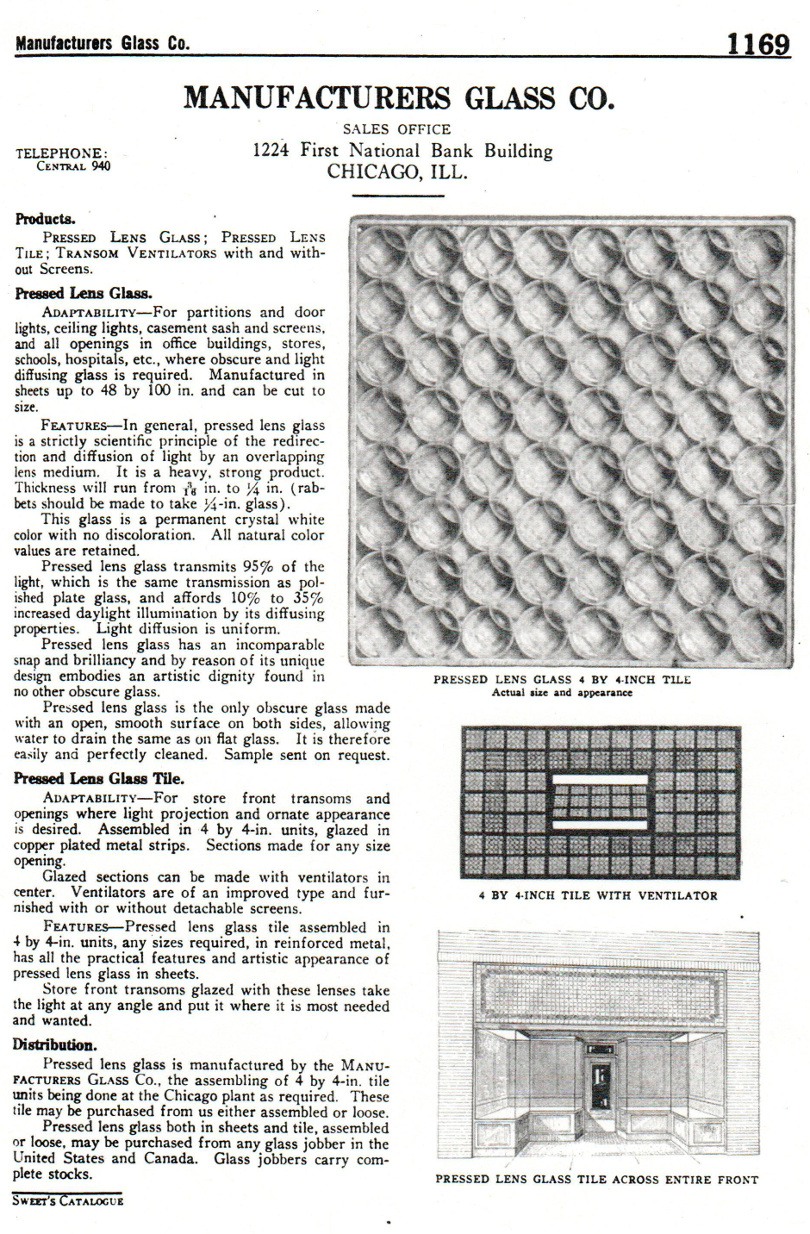

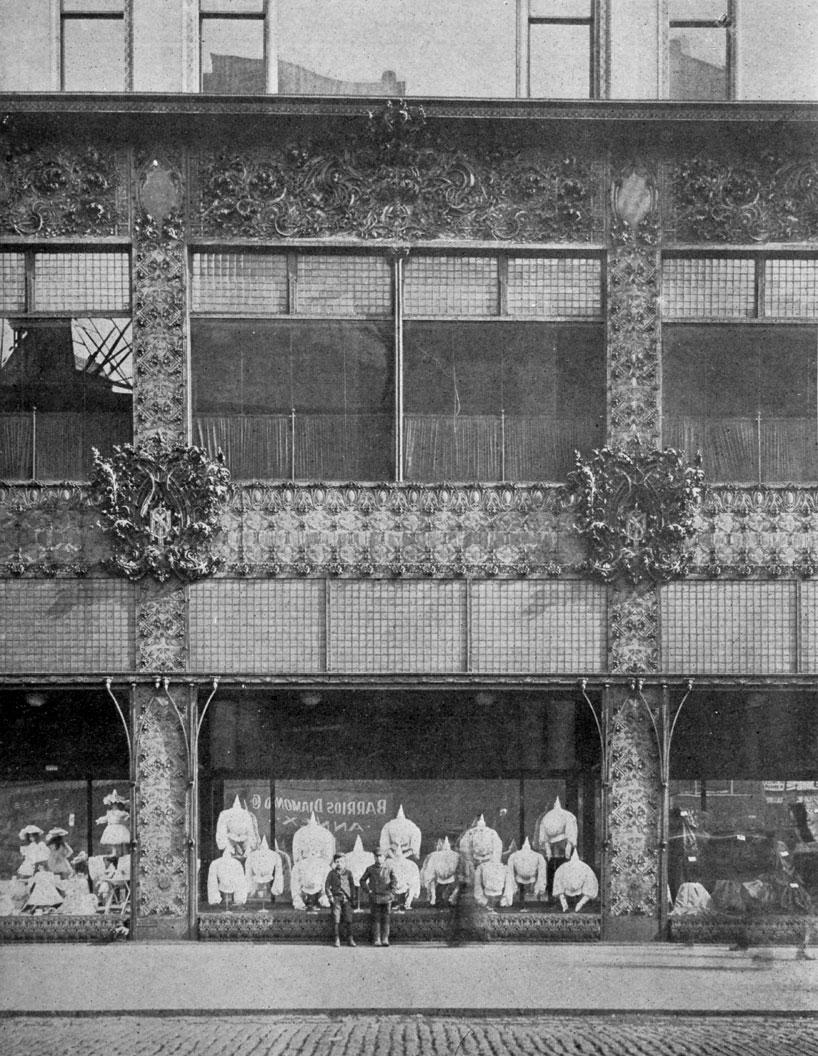

While Luxfer feverishly defended their patent, other companies competed with them for this growing market. Three notable competitors were the Daylight Prism Company7, the American 3-Way Prism Company8, and the Manufacturers Glass Company. All three had many Chicago installations, and did their best to show their wares, publishing advertising catalogs that extolled the virtue of their products.

Daylight Prism Company

1904 Sweet’s Engineering Catalog

Louis Sullivan made use of prism glass, and it is featured prominently in many of his constructions. The Gage Building, designed by Holabird and Roche, has a facade done by Louis Sullivan at the request of the Gage Company.

“The Gage Building is three bays wide. Casement windows originally filled the bays: a series of five occupied the central bay and the two flanking bays each had four. Across the top of each group of windows was a four-foot-high band of translucent Luxfer prisms. These are glass tiles that have one side formed into prisms so that light passing through them is evenly diffused throughout the interior space. Sullivan’s critics thought that this was mere ornamentation and that it reduced the amount of natural light needed for interior spaces where intricate handiwork was done. Actually, direct sunlight is often too strong for exacting needlework, a fact demonstrated in early photographs of the Gage Group where the shades are half drawn. Sullivan’s use of Luxfer prisms was actually a compromise between admitting the necessary amount of light and admitting too brilliant a glare, according to Sullivan’s biographer Hugh Morrison. Bands of double-hung windows now fill these openings.“9

Ryerson-Burnham Libraries, Art Institute of Chicago, Richard Nickel Collection

Even though the glass is long gone from the Gage Buildings, the current building pays tribute to prism glass with a grid pattern in the transoms, nicely echoing how it used to look.

Joe Sislow

Luxfer glass was even present in Adler & Sullivan’s Stock Exchange building, visible here as canopies outside the window.

Pocket Hand-Book of Electro-Glazed Luxfer Prisms

Sullivan also used the windows prominently in the Schlesinger & Mayer store, which eventually became the Carson Pirie Scott building. The original design by Sullivan used prism glass heavily to transfer light into the store. When the building was renovated in the 1920s, the prism glass was removed. While restoring the building, serious consideration was given to restoring the prism glass. Sadly, they opted for clear glass.10

Ryerson-Burnham Libraries, Art Institute of Chicago, Richard Nickel Collection

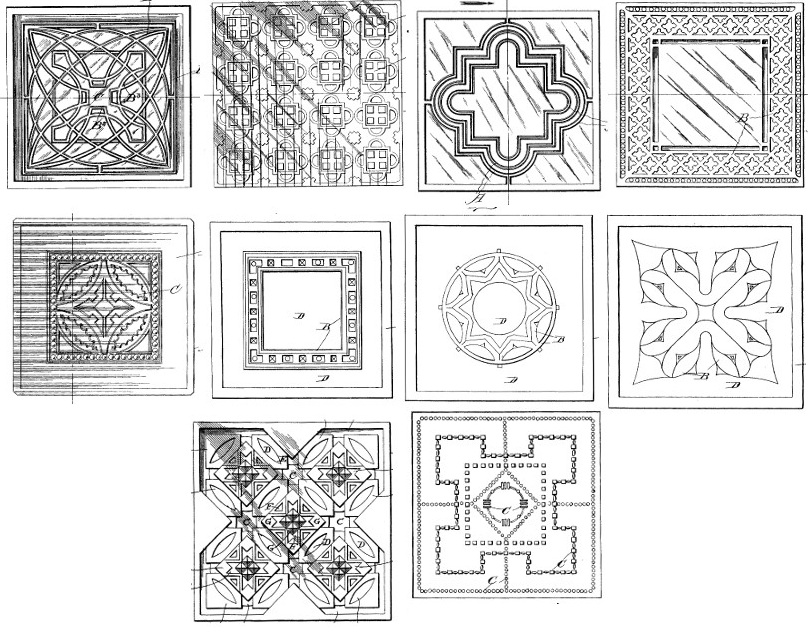

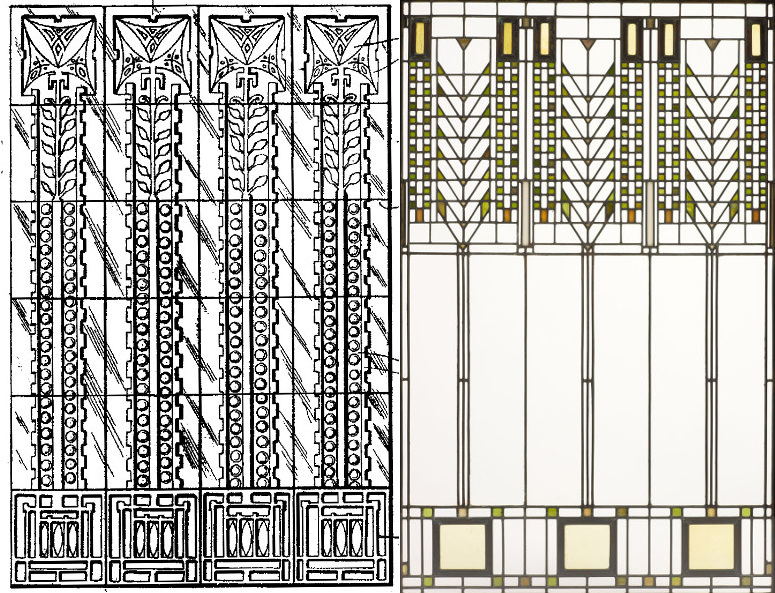

Frank Lloyd Wright is hardly what anyone would call forgotten around Chicago, but even he had some surprising ties to Luxfer glass. In 1897, Luxfer hired an aspiring young Wright to design prism tiles for their line. Wright completed and patented over 40 designs for Luxfer, only one of which was produced. Most of these patents are long forgotten, with only the produced image (upper left corner in the image below) being marginally used by the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. The rest have only been seen in a few architectural articles over the years.

US Patent & Trade Office

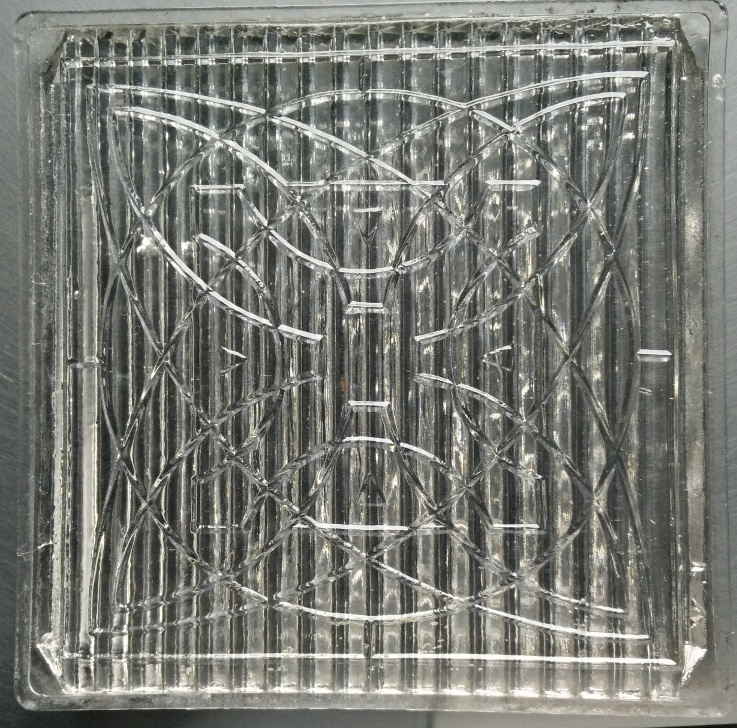

Joe Sislow

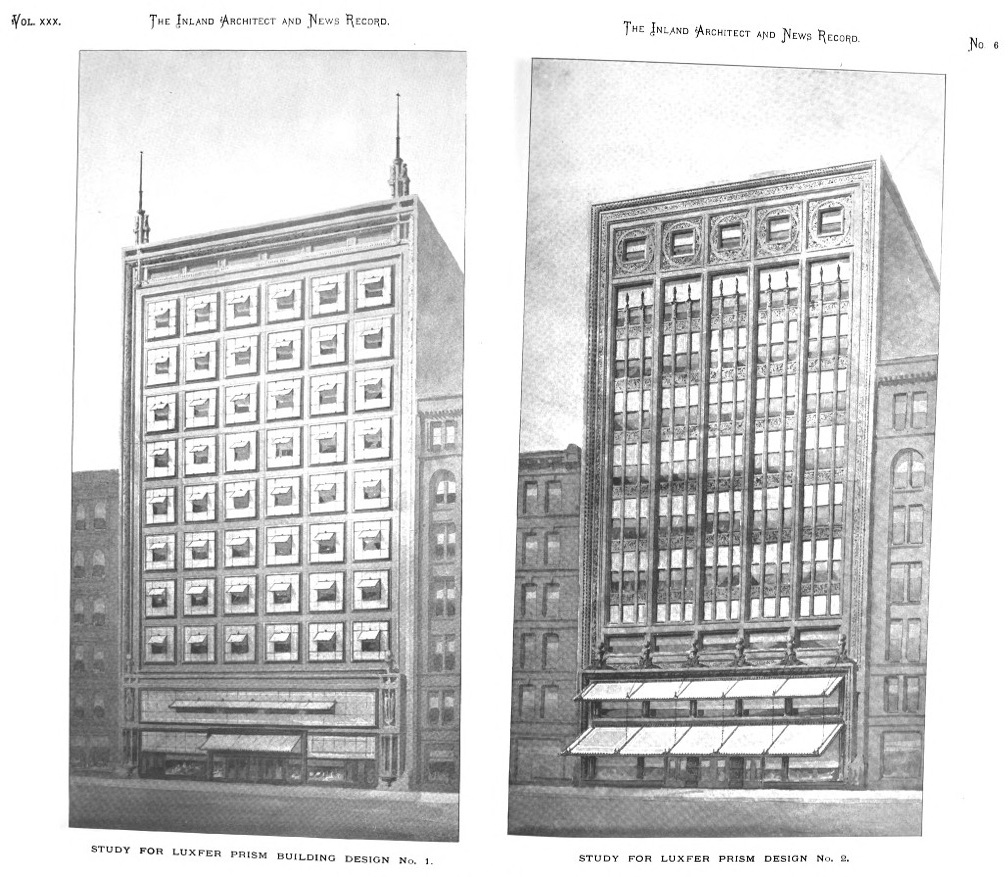

To capitalize fully on the architectural possibilities of their product, the company launched a design competition. Taking place early in 1898, Chicago’s architects were well represented as judges: William Le Baron Jenney, William Holabird, Daniel Burnham, and Wright. Two designs were given as examples of possible buildings using the glass. Both designs were eventually credited to Wright, and many architectural sources site these designs as some of the earliest examples of modern skyscraper design.11

Inland Architect and News Record, 1898

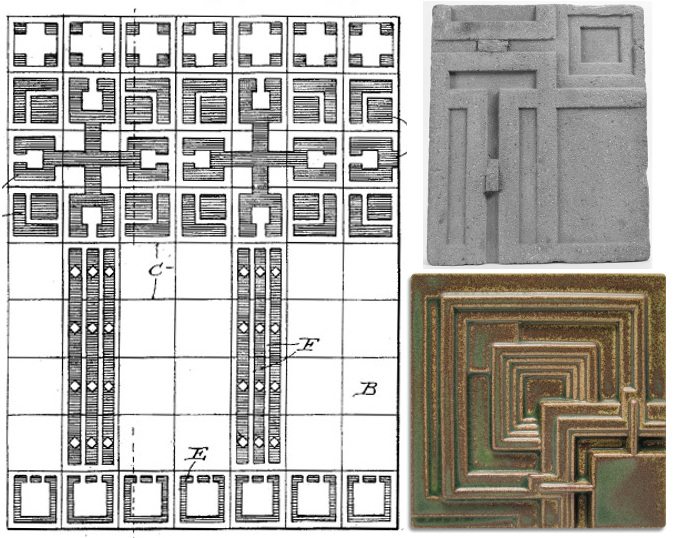

Frank Lloyd Wright carried his work for the Luxfer company throughout his career. First, he had many designs that weren’t used that he seemed to keep within reach. He was obviously influenced by the modular design that tiles could provide, and two specific examples line up with an unused pattern. First, the tile work on the Ennis House (1924), and second the tile work on Midway Gardens (1914, another building that is woefully unknown and underappreciated in the history of Chicago). Wright was clearly playing with the same sorts of abstract geometric tiled designs he would later use.

Left: 1897, US Patent & Trade Office Right top: 1914, Art Institute of Chicago Right bottom: Motawi Tileworks

Second, one of Wright’s most iconic glass designs was the Tree of Life design for the Darwin D. Martin House. This design shows some similarity to another patent he did for Luxfer. The pattern definitely underwent some evolution with Wright’s growth, but the seeds of the design are clear to see in one of his Luxfer patents.

Left: 1897, US Patent & Trade Office Right: 1904, Art Institute of Chicago

Finally, in the 1930s while working on the S.C. Johnson factory, Wright was experimenting with glass at Taliesin. He requested designs from Luxfer, but he wound up using the Corning glass tubing that are now a signature of the office complex. But even almost 40 years later, he still considered using Luxfer glass.12

Joe Sislow

One of the reasons that both Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Sullivan made a connection with Luxfer was that for a time, all three of them shared offices in The Rookery.13 In fact, of all of the locations in and around Chicago with prism glass still extant, The Rookery is one of the few to still have not only vault lights (indoor, no less) but a distinct non-typical retail/office use (non-transom, which is more typical of retail installations) of 4×4 prism glass.

Joe Sislow

Joe Sislow

All through the 1920s, a plethora of factors contributed to the downfall of prism glass. First, the louvered design made cleaning of the panels themselves difficult, often making the windows allow in less light than normal windows.

Architecture Magazine, 1908

Second, electric light had grown in popularity, reducing the need for such light-efficient designs. It was far more hip to show the open use of electric light (and ostensibly the money to wire up locations & pay for electricity) than to worry about conservation.

Third, styles changed. Minimalism and modernism rose thru the 1920s, and the quaint detail of the prism glass appeared old fashioned. Sleek was in, and the detail of the glass didn’t fit with such ideas.

Fourth, air conditioning also increased in usage starting in the 1920s. Many of the old storefronts had high ceilings which could easily be repurposed with duct work. Ducts were ugly, so hiding them with drop ceilings was an obvious solution. The drop ceilings covered the high transom windows that often had the prism glass, rendering them useless.

Fifth, the windows weren’t as durable as advertised. Few of the canopy versions survived the elements like hail, ice, etc. Electro-glazing had issues that possibly caused cracking. Windows that weren’t electro-glazed had zinc or lead between the panes, and that disintegrated over time. The Great Depression can’t have helped with the cost of maintaining such windows.

Finally, the use of advertising and signage grew through the 1920s and 1930s. Many shops were far more interested in larger areas for their signs, and the transom areas above display windows were a natural place for signs and awnings. Without the need for natural light (due to the spread of electric light), it was a hard argument to keep those windows dedicated to prism glass.

If you look at many of the older Chicago storefronts today, you can see the shadows of where prism glass would have been, hidden behind boarded up transoms and tucked behind signs and awnings.

Joe Sislow

Extant Prism Glass in and around Chicago

We are lucky to have remnants of this intriguing chapter in architecture still visible in Chicago. Below are some pictures of some extant prism glass, courtesy of the author.

Joe Sislow

Joe Sislow

Joe Sislow

Joe Sislow

Joe Sislow

Joe Sislow

Joe Sislow

Joe Sislow

Joe Sislow

Joe Sislow

If designs had worked as planned, prism glass would be everywhere. Instead, we have a newer entry into the field of glass. In part 2, we will discuss the rise of glass block, how it took the architectural world by storm, and how it came to be so ubiquitous.

Besides the sources below, I would like to give special thanks to Jeff Burke of Luxfer Prism Glass Tile Collector and Ian Macky of glassian.org. Their tireless efforts to categorize the remains of this beautiful technology gave countless leads and sources of inspiration for this article, not to mention their welcoming nature in answering my questions via email. You could spend a worse weekend than exploring their web sites.

I would also like to mention Dietrich Neumann, without whom I wouldn’t have been able to track down nearly as much information. His article, criminially underappreciated by both interest and being locked away behind a paywall, should be mandatory reading for anyone interested in prism glass & Luxfer.

Finally, the Google map of prism glass locations will be constantly updated with new locations and information as I find them.

Building Walls of Might: The Development of Glass Block and Its Influence on American Architecture in the 1930s – Elizabeth Fagan, Columbia University, May 2015

The Century’s Triumph in Lighting: The Luxfer Prism Companies and Their Contribution to Early Modern Architecture – Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 54, No. 1 – by Dietrich Neumann

Daylight Prisms – Daylight Prism Company, 1900

Inland Architect, 1898

Nyon Archives (Gustave Falconnier picture, courtesy glassian.org)

Pocket Hand-Book of Electro-Glazed Luxfer Prisms, Containing Useful Information and Tables Relating to Their Use – American Luxfer Company, 1898

Restoring Historic Metal Facades – Gordon Block

The School of the Art Institute – Richard Nickel photo collection

Sweet’s Engineering Catalog, 1904

US Patent and Trade Office

The World’s Work, November, 1903 (uncaptioned Luxfer Prism Ad)

2. Patent No. 312,290, USPTO, James G. Pennycuick, February 17, 1885

3. The Century’s Triumph in Lighting: The Luxfer Prism Companies and Their Contribution to Early Modern Architecture – Dietrich Neumann; The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 54, No. 1, pg. 26

5. Pocket Hand-Book of Electro-Glazed Luxfer Prisms, Containing Useful Information and Tables Relating to Their Use – American Luxfer Company, 1898

7. Daylight Prisms – Daylight Prism Company, 1900

8. Daylighting: Prism Transoms, Sheet Prism Glass, Diffusing Tile, Sidewalk Lights, Floor Lights, Skylights, Sidewalk Doors, and their Accessories – American 3 Way Luxfer Prism Co, 1920

9. The Gage Group – Preliminary Summary of Information Submitted to the Commission on Chicago Historical and Architectural Landmarks in August 1981

10. Restoring Historic Metal Facades – Gordon Bock http://www.traditionalproductreports.com/timber-heavymetal.html

11. The Century’s Triumph in Lighting – Neumann, pg. 30

12. Frank Lloyd Wright and the Johnson Wax Buildings – Jonathan Lipman, Frank Lloyd Wright, pg. 65

13. The Rookery Building, Alterations, Frank Lloyd Wright Trust http://www.flwright.org/researchexplore/wrightbuildings/rookerybuildingalterations

- East Side Trust & Savings Bank

- American Licorice

- Our Historic Subway Stations

- Webster Company

- Storefronts