Looking at fiction films shot on location in Chicago as documents of a real place, three prevalent themes emerge. These themes are not necessarily exclusive to Chicago; they can apply to any city (aside from Los Angeles or New York) which have been locations for a decent number of films. Pittsburgh and Toronto come to mind.

1. The city is like an typecast actor who portrays numerous iterations of a similar character across a series of films.

2. The relationship between the real city and the filmed city is often spatially incongruous.

3. After approximately twenty years, films shot in the city become unintentional documentary records that reflect changes in the built environment.

Considering Chicago’s film appearances like that of an actor’s, the similarities outweigh the differences. There are certain stock ways in which Chicago is represented, and certain places that are frequently present. Reflecting the relationship between the central area and the surrounding neighborhoods, films will often be shot partly in a specific neighborhood, Pilsen for example, and partly in the Loop. The central area versus the neighborhoods is a subtext spanning the history of the filmed city, mirroring the real city.

The Loop and Rush Street are used frequently, while the appearance of individual neighborhoods is sporadic at best. The neighborhoods that do appear are almost invariably those on the North side along Lake Michigan. These include the Gold Coast, River North, Old Town, Lincoln Park, Lakeview, and Uptown. Wicker Park and Pilsen have been used frequently as well. These areas share what is perceived as a traditionally urban physicality. A notable exception to this is The Psychotronic Man (1980), which is shot in places like Oak Park and Skokie, however, scenes were also filmed atop the Wrigley Building. The Psychotronic Man is notable more for its campy low-budget feel and indescribable weirdness.

In order to immediately establish the location as Chicago, there will always be either an establishing shot of the skyline or the L — commonly both. Perhaps these are the most obvious unique features which differentiate this city from others, quickly summarizing it with frugal imagery. The moviegoer only needs to see the clock tower atop the Wrigley building or see the L train in the window in order to place the film.

A good example of this is City That Never Sleeps (1955), which begins with a time lapse shot of the skyline, prominently including the Wrigley and Tribune buildings. As the sun sets and all the buildings light up, an omniscient narrator explains what otherwise could be inferred:

And so the scene is set for an otherwise melodramatic and banal cop movie.

Call Northside 777 (1948) begins somewhat less poetically with a special effects shot of the Great Fire smoldering, before cutting to an aerial shot of the skyline. A narrator provides a two minute history lesson spanning the Fire to Prohibition, telling of “a short history of violence beating in its pulse.” These introductions used in films of the 1940s and 50s are intended to quickly provide context, creating an image of Chicago as a place of extreme contrast – socially, economically, and physically.

Although there aren’t many (thank Daley I), films from the 1960s tend to take more varied approaches to the establishing shot. From the 1970s on, the inclusion of the skyline again becomes de rigueur. A notable violator of the skyline convention, Goldstein, begins with a conversation on a now-unidentifiable run down street that is probably in pre-gentrification Old Town. The skyline is never shown throughout the film, although we are treated to a midnight ride on the ‘L’ through Woodlawn.

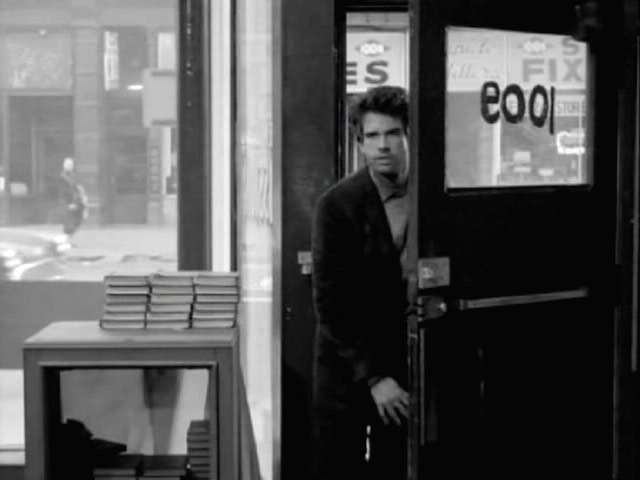

Mickey One (1965) begins in Detroit, of which very little is shown. Mickey, the protagonist-on-the-run, arrives in Chicago by rail. Interestingly, he is shown on a Chicago & Northwestern Train, which never served Detroit, pulling out of Northwestern Station. We’re given a view of warehouses in the foreground, the corporate skyline dominated by the manufacturing skyline, and relegated to the background. Mickey jumps off the train into a wrecking yard, presumably on the west side. Instead of beginning with the obvious establishing skyline shot, Mickey One begins symbolically in the scrapheap, reflecting Mickey’s descent from high society to the lower depths and back.

In a fiction film, the location is always a backdrop for the plot. This type of film is concerned primarily with human drama and less with accurate and comprehensive depiction of place. Films set in Chicago often relegate the city to a supporting role. It may get plenty of screen time, but it is not the star.

In some instances, it doesn’t even matter in which city the action is taking place. This seems to hold true especially in cases where the action shifts between places, as happens in North by Northwest (1959). Thornhill could have fled from New York on a train bound for Boston, Baltimore, or Denver, just so long as he arrives at Mount Rushmore in time for the suspenseful finale. Just as the microfilm used as a plot motivation in the film was a McGuffin, the use of Chicago as a location was equally arbitrary. It could have been any large American city.

Specific locations are also unimportant when the film is heavily fictionalized either in terms of time or place. The Sting (1973) is a good example of both. Depicting a romanticized view of 1936 Chicago, it was filmed in 1973 primarily on elaborate studio sets. The one scene in the film that involves interaction with a real place is a chase sequence in and around the 43rd Street L station. Observant viewers will notice that this chase scene is full of historical inaccuracies, most notably the presence of A/B skip-stop signage which was not introduced until 1948. This scene could have been filmed on elevated trains in New York, Philadelphia, or Boston and few audience members would have noticed or cared, as the plot would remain unaffected by discrepancies of place.

On the other hand, there are some films where Chicago plays more of a lead role – when the specificity of location is integral to the plot. The best example of this is Medium Cool (1969), a film that sets a fictional story about a romance between an Appalachian mother and an amoral cameraman against the backdrop of the 1968 Democratic Convention. During the final act of the film, the actress portraying the mother, Virginia Bloom, is filmed wandering about, in character, amidst actual violence in the streets during police riots. Because of this, Medium Cool is uniquely valuable as a historical document in ways that far exceed its impact as a work of fiction.

Within the context of a narrative, locations are important for different reasons. The location can very quickly describe a great deal about the socio-economic status of the character. If a single woman lives in an apartment building in the vicinity of Rush Street, as does Theresa in Looking For Mr. Goodbar (1978), it has a different meaning if she were to live in a single family frame house on the Near West Side. Arguably, her Madonna/Whore complex would be less believable if she wasn’t living in a seedy nightclub district.

Taken a step further, different locations create different implications about the nature of the depicted action. For example, the shootout sequence in Bad Boys would have been less effective if it had taken place somewhere like Lake Forest rather than Little Village. In Bad Boys, a car full of black gang members are driving down Cermak Road to meet a group of Mexican gang members in order to carry out a drug deal. In an example of un-subtle foreshadowing just before the deal goes awry, one of the black gang members remarks, “rough neighborhood.” Although this is a clear manipulation of the audience’s perceptions and prejudices– even the gang member feels unsafe in this place – the surrounding area needs to look rough to the audience for the effect to work.

Within films, liberties are often taken with relationship of sequential locations to each other. This occurs famously in The Blues Brothers (1980) where, in the middle of a chase scene the action jumps from Park Ridge to Harvey in one cut. When this is done, the city is spatially condensed. Relationships such as distance and scale become distorted, even meaningless. If most of the audience can’t tell the difference, why does it matter if in one scene, Jake and Elwood drive from Park Ridge to Harvey, or in another part of the film, from Wauconda to the Loop, to Milwaukee, and back? Locations are utilized for their appearance and are in this way interchangeable.

This cut-and-paste approach to place furthers the gap between the real city and what James Sanders describes as “a place of mind and spirit – a mythic city.” The mythic city, a fictional version of a real place, is just as much the creation of writers and directors as any other element of a film. There is a fine distinction between the appearances of individual places and their employ in the fictional narrative, a rupture only explored in Medium Cool. However, Medium Cool is a meditation on the role of the media and filmed reality versus ‘real’ reality, and is in this way unique.

When a location in a film has a connection to the real place outside of the film’s narrative, the film becomes an incidental document of the built environment. An image of the most banal storefront will become interesting in time as a record of change, if nothing else. Because films depict motion, they augment our understanding of places seen otherwise through still images. Looking at it this way, the mythic city takes a subordinate position to historical record, but this is an uncommon way to read a film. Needless nerdiness notwithstanding, examples of this can be drawn nearly every film shot in Chicago that is at least twenty years old.

The concept of the unintentional documentary begins at the beginning with Call Northside 777, the first non-silent feature (‘Hollywood’) film to be shot on location in Chicago. Call Northside 777 is a wrong-man-accused-of-the-crime docu-drama based on a true story. In the film, the South Loop and Noble Street are used to portray the Back of the Yards. Even though the idea was to convey the rough and tumble world of Polish taverns in Back of the Yards, we’re left with an excellent visual record of another long-gone commercial district on the northwest side.

Cooley High (1975), a film about author Eric Monte’s experiences growing up in the Cabrini-Green housing projects, is replete with unintentional documentary images. Most of the locations have been either demolished or significantly altered in the past thirty years. Much of the public housing structures shown in the film were demolished in the mid-2000s, as part of what can be called urban renewal-renewal. Many, if not all of the frame houses on Larrabee, Howe, and Elm streets depicted in the film are subjects of the past. Protagonist Preach and his girlfriend are shown canoodling along the Ogden Avenue viaduct, which was demolished in 1992. Even the titular school is no longer with us.

There are conventional ways the city is treated on film. For example, we begin with an opening shot of the skyline, then cut to a streetscape in one of the North side lakefront neighborhoods, and then downtown for, lets say, an action sequence. In this action sequence, the relationship between real places is incongruous, and the appearance of place is more important than spatial continuity. In the twenty years since this action sequence has been filmed, the locations have changed to the point where the scene has become interesting and valuable as something other than an action sequence. Viewing a series of films with this in mind, the line between fiction and reality becomes blurred, and space and time are compressed. Although it is an illusion, Sanders’ Mythic City, the past can briefly seem ever so slightly more accessible and real.

James Sanders. Celluloid Skyline: New York and the movies. New York: Knopf, 2001.

Filmography

Bad Boys. Dir. Rick Rosenthal. Universal Pictures, 1983.

The Blues Brothers. Dir. John Landis. Universal Pictures, 1980.

Brannigan. Dir. Douglas Hickox. United Artists, 1975.

Call Northside 777. Dir. Henry Hathaway. 20th Century Fox, 1948.

City That Never Sleeps. Dir. John H. Auer. Republic Pictures, 1953.

Cooley High. Dir. Michael Schultz. Perf. Glynn Turman. American International Pictures, 1975.

Goldstein. Dir. Philip Kaufman. Montrose Film Productions, 1965.

The Hunter. Dir. Buzz Kulik. Paramount Pictures, 1980.

Looking For Mr. Goodbar. Dir. Richard Brooks. Perf. Diane Keaton. Paramount Pictures, 1978.

Medium Cool. Dir. Haskell Wexler. Perf. Virginia Bloom. Paramount Pictures, 1969.

Mickey One. Dir. Arthur Penn. Perf. Warren Beatty. Columbia Pictures, 1965.

The Monitors. Dir. Jack Shea. Commonwealth United Entertainment, 1969.

The Monkey Hustle. Dir. Arthur Marks. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1976.

North by Northwest. Dir. Alfred Hitchcock. Perf. Cary Grant. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1959.

The Psychotronic Man. Dir. Jack M. Sell. International Harmony, 1980.

The Sting. Dir. George Roy Hill. Universal Pictures, 1973.