Chicago historian Dominic Pacyga characterizes Chicago as a snake that transforms itself every generation, shedding its old skin to emerge a new and different creature. The city’s neighborhoods reflect various social incarnations that can be read as layers in the surrounding cityscape. This is certainly true of Avondale, which began as a suburban industrial-proletarian enclave, transforming over time into a haven for political refugees as well as an entrepot for short-term migrant laborers from Poland. The area’s plethora of factories and warehouses typecast it as the “neighborhood of smokestacks and steeples”. Florsheim Shoes, Olson Rug and a slew of other companies produced goods for the entire country here, taking advantage of the nearby Chicago River and the City’s extensive rail network.

Matthew Schoenfeldt, c.1970s

The history of Avondale begins in the quiet prairie surrounding Chicago, incorporated as Jefferson Township in 1850. Two Native American trails through the area were planked, becoming the Upper and Lower Northwest Plank Roads, routes traversed largely by truck farmers en route to sell their goods at the Randolph Street Market. Known to us today as Milwaukee and Elston Avenues, these two diagonal thoroughfares break up the monotony of the city’s otherwise ubiquitous grid.

Avondale was first incorporated as a village in 1869. Although settlement in the area begins with the extension of the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific tracks to Milwaukee in 1870 and the building of a post office at the corner of Belmont and Troy at a stop of the Chicago & Northwestern Railway in 1873, significant development did not take place until Jefferson Township was annexed to the city in 1889. The city improved the level of local infrastructure, paving Milwaukee Avenue. Access to the city improved with the extension of the Milwaukee streetcar line to Jefferson Park and the building of the elevated train in neighboring Logan Square.

Left: SC, 2009 Right: DP, 2004

These improvements resulted in Avondale’s rapid development as people poured in from the overpopulated districts closer to the city core. Working-class people one-hundred years ago saw the area as an opportunity to get away from the grind of crowded urban life close to the city-center, where in the words of Historian Ellen Skerrett, “trees- much less parks- were few and far between.” One researcher calculated that in the late 19th century, the population density in the vicinity of Grand and Milwaukee was greater than the legendary “black hole” of Calcutta.

Within two decades after annexation, the population in Avondale had reached just over 38,000, by 1930 it was considered to have reached maturity. Much of the population was foreign-born. While Poles were the primary group west of Kedzie, Germans and Scandinavians comprised a sizable population east of Kedzie to the south of Belmont, with a smattering of Italians later entering the area.

SC, 2009

Poles, who have today become synonymous with Avondale, first moved to the area beginning in the 1890’s. Historian Edward Kantowicz maintains that Milwaukee Avenue’s role as the chief route between the old Polish Downtown and St. Adalbert’s Cemetery in Niles is the reason for the spread of Chicago’s Polish community along this street. Kantowicz cites the fact that the funeral processions down Milwaukee Avenue gave Polish immigrants to Chicago the opportunity to become well acquainted with the empty lots in its vicinity, giving rise to the city’s infamous “Polish Corridor.”

The author of a 1913 Chicago Tribune piece described the area this way:

On past Irving Park boulevard and into Avondale, where the names on the street signs make evident that this is a Polish neighborhood, “Ski” is the regular terminal, while the trim brick flats and shop buildings and the well kept, well paved side streets leading off from the avenue declare that these people are well to do and enterprising. Where Belmont Avenue cuts diagonally across Milwaukee Avenue there is a big holding of vacant land by a New York man, who is waiting to cash in on the movement increment built up by the busy immigration.

SC, 2009

Situated between the Victorian era mansions on double lots in Old Irving and the stately Graystones along Logan Boulevard, Avondale’s architectural stock is comprised of modest frame two and three flats, brick Italianate two-flats, and bungalows. The overall housing stock, typical of Chicago’s “Bungalow Belt,” reflects the more modest livelihood of Avondale’s residents relative to its upscale neighbors. Opulent architecture in Avondale is something that is found not on its residential streets but in its temples.

An excellent example is the Basilica of St. Hyacinth with its characteristic three-towered façade that is surely one of the city’s finest examples of the so-called “Polish Cathedral” style of architecture. With seating for over 2,000 people, stained glass windows imported from the workshop of F.X. Zettler of Munich, massive bronze doors cast by Czesław Dźwigaj, and its painted saucer dome measuring 3,000 square feet with over 150 figures, the Basilica is an impressive house of the holy.

SC, 2009

Nearby St. Wenceslaus employs a more modern aesthetic and is considered to be “one of the best examples of the fusion of Art Deco stylings with medieval European architecture in the city of Chicago.” The purgatorial shrine here was designed by famed artist Jan Henryk De Rosen, responsible for the famous frescoes of the Armenian Cathedral in L’viv, Ukraine, as well as prominent pieces in both the Anglican and Catholic Cathedrals in Washington DC.

An interesting aside is in looking at how these two churches functioned as fora within which Poles could pay homage to important events in their social history that they were unable to talk about or commemorate openly during the Communist regime. A monument to Jerzy Popiełuszko, a dissident priest murdered by the secret police sits in the “Garden of Memory” alongside the Basilica, while inside the left end of the church’s narthex is a niche with an urn of soil from the Katyń forest, the site where thousands of Poles were murdered by Stalin.

DP, 2004

Avondale remained a blue-collar neighborhood through the 1960s when the area entered a new phase tied into two distinct changes. The first had to do with the exodus of Polish-Americans out of the old Polish Downtown in what we now call Wicker Park, which had been the historic center of the city’s Polish community. The second had to do with a gambit on the part of the Polish communist government to get people out of the country.

Unlike the travel restrictions imposed by other communist governments, Poland turned a blind eye as folks went on “working vacations,” going overseas and bringing back sorely needed hard currency for their failing economy. The government owned everything, and didn’t have enough money to produce enough goods for its own people. The result was that stores were usually empty, save for mustard and vinegar, and one had to network and schmooze to get anything from clothes to toilet paper. As a result, a unique economy developed in Avondale, as countless Poles came to make more money working as a contractor than they had in their whole lives as doctors, lawyers and countless other professions.

DP, 2004

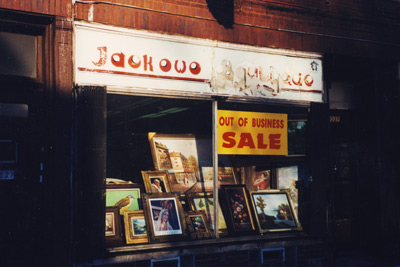

The retail fabric of the neighborhood began to reflect this new economy. The area became dominated by a host of institutions and services most relevant to these inhabitants. Among these were businesses shipping domestic goods to Poland, numerous work agencies, Polish restaurants and delis to quickly and cheaply buy food in between jobs, and a whole slew of nightclubs in which to let loose on the weekend.

Because of the extensive social infrastructure in the area, living in Avondale was extremely attractive to these transient foreigners. Locals claim that because of this intense demand, rents charged in the neighborhood were higher than in posh areas of the city such as Lincoln Park or Old Town.

Community Public Art Guide, 1975

SC, 2009

The situation became more complex as Avondale also became a haven for the flood of Solidarity refugees that came fleeing in the 1980s. In opposition to the “vacationers” who were primarily concerned with making a quick buck, these were political activists who were concerned with putting roots in the community. Finding themselves in an environment where they could finally express themselves freely without worrying about incurring the wrath of government censors or political repression, they fostered a distinct flowering of Polish arts and culture in Avondale. A highly expressive and now unfortunately decaying mural in the McDonald’s parking lot combining Polish patriotic and folkloric motifs stands forsaken near the corners of Belmont and Pulaski in mute testament to this bygone renaissance.

DP, 2004

Prosperity destroys as much as it creates. Today this economy in Avondale’s Polish Village is coming to an end. Better economic prospects in Poland as well as the movement of local Poles and Polish-Americans to outlying neighborhoods is bringing about change once again.

Left: SC, 2009 Right: DP, 2004

Other immigrant groups from the former Soviet Bloc, such as Ukrainians, Belarusians and Czechs have moved in. The area however still retains much of its Polish character, with Polish bakeries, restaurants, businesses and even a department store visible in its landscape, but with signs in these other related languages to cater to this new clientele.

SC, 2009

Like neighboring Logan Square, the area is also experiencing gentrification as artists and young professionals, like the Poles and Latinos before them, move their way northwest along Milwaukee Avenue. As in other Chicago neighborhoods, change is sure to be the one constant in Avondale’s history.