In terms of using images to study the built environment, postcards are probably the farthest one can get from “proper” documentary efforts, such as the Historic American Buildings Survey. Postcards are purely commercial; a form of mobile advertising which often present idealized depictions of places. They are a direct descendant of cartes-de-vistes of the mid-19th century, which by the turn of the century, became mass produced objects whose relationship to photography was tenuous. Many postcards were not simply photographic prints or reproductions, but drawings made from reference photographs. There was room for manipulation, which again, makes them somewhat unreliable as documents.

But not completely unreliable. On this page, we’ll use postcards as the basis for a then-and-now of specific buildings and their histories. We’ll see that re-contextualized from the “wish you were here” sentiment to a “what was there” perspective, postcards are actually excellent documents.

For your reference, the best online sources for Chicago postcards are, in order:

1) Lake County Discovery Museum’s Curt Teich Archives

2) Chicago History in Postcards

3) Chuckman’s Collection of Vintage Chicago Postcards

All of the postcards on this page come from one of the three. For some reason, the Chicago Postcard Museum is less than useful, something you wouldn’t expect from the name.

If you haven’t guessed yet, we will not be viewing the past through rose-tinted glasses. We lied! On to the content…

Left: Lake County Museum, Curt Teich Postcard Archive. Right: Call Northside 777

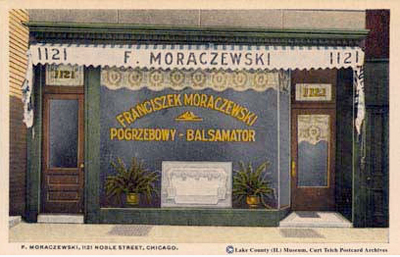

“Pogrzebowy” is the Polish term for a funeral director, and a “balsamator” is an embalmer. This makes sense, as this small storefront was once directly across the street from Holy Trinity, one of Chicago’s oldest Polish Catholic Churches.

Most of the area surrounding Holy Trinity (above right) was razed in 1970, including the storefront at 1121 N. Noble, to make way for the Noble Square Co-Op Townhomes, and Noble was converted into a quite small street. Walking on it today, you’d find it difficult to believe it was once a lively commercial thoroughfare. This area was immortalized on the silver screen, albeit briefly. In Call Northside 777, McNeal can be seen snooping around the old neighborhood searching for Wanda Skutnik.

Left: Lake County Museum, Curt Teich Postcard Archive. Right: Chicago History In Postcards.

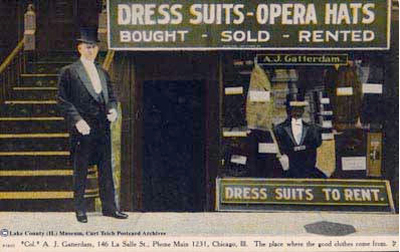

Phone Main 1231, now that’s far more historically accurate than ‘Northside 777’, as far as phone numbers go. A number such Main 1231 with an un-prefixed exchange followed by four digits dates this postcard somewhere in the 1910s. This is confirmed by the fact that the address listed here, 146 (N) LaSalle, is post-Brennan, that is, it refers to the current system, which was enacted in 1911 in the central area. Moreover, A.J. Gatterdam, owner of this tailoring business, “got tired of handing out plug hats and swallow tails to smirking bridegrooms-to-be, politicians, and after dinner speakers”, as a 1919 Tribune article puts it.1 One could say that he pulled up his tails and went out of beeswax. Ha!

The shop was located in the Lafayette Building on the corner of Randolph and LaSalle, which was demolished in the early 1920s to make way for the Hotel Bismarck and Metropolitan Buildings, collectively known as the Eitel Block, as seen in the right image. This block of buildings is still standing.

Left: Lake County Museum, Curt Teich Postcard Archive. Center: American Terra Cotta Company Photographs, University of Minnesota, 1937. Right: City of Chicago, c.1970.

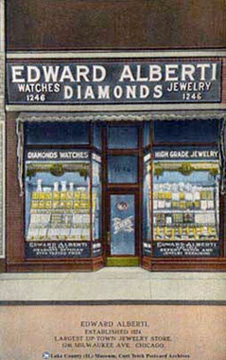

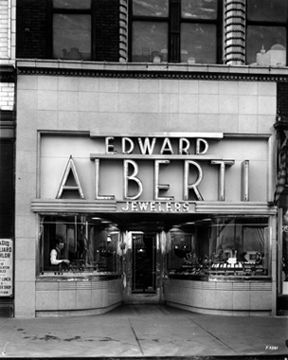

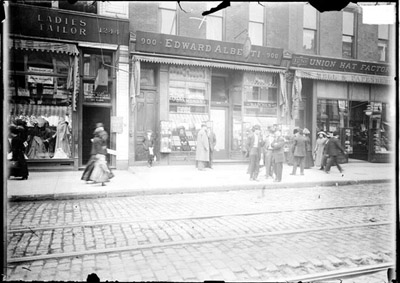

Alberti Jewelers was founded in 1874, and remained in the same location, 1246 N. Milwaukee, for around 90 years. Prior to WWII, Alberti sponsored a number of amateur sports teams, most notably a women’s bowling team. The Tribune ceases coverage of such teams in 1952, and by 1963, Alberti was out of business.

Center: In 1937, Alberti’s was given a facelift with this Michaelson & Rongstad-designed Art Moderne facade. This design outright rejects its predecessor and embraces the “modern”. Unnecessary detail is trimmed away, and cleanliness is emphasized. The signage, rendered in a Kem Weber-esque typeface, is featured prominently. The curved glass window and recessed front door are typical of storefronts of this era, and many can still be found along Milwaukee Avenue.

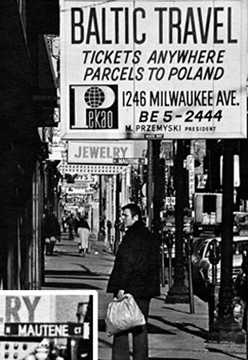

The image at right, taken circa 1970, includes a sign for a Polish travel agency located at 1246 N. Milwaukee. Bank Pekao is a Warsaw-based bank catering to Poles living abroad, thus the global ‘P’ logo.

Left image: Chicago Daily News. Right image: Cook County Assessor’s Office.

Left: Alberti Jewelers in 1911, two years after the implementation of the modern address system outside of the Loop. Here, the tailor and haberdasher surrounding Alberti have updated addresses, while Alberti does not. But as we saw earlier, they eventually caught up with the times.

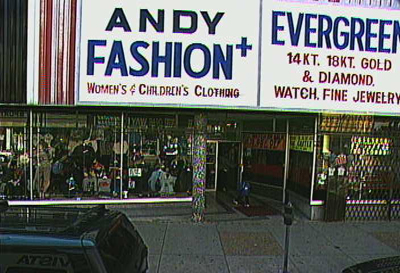

Right: By 2000 (earlier actually), Milwaukee and Division had become a mini ‘Wig Store Downtown’. But gentrification was not far off…

Left: Chicago History in Postcards.

See? We should probably be more evenhanded here, but this intersection and the surrounding area is currently the epicenter of a cultural-shift clusterfuck (rapid gentrification) that we don’t even care to think about beyond the end of this sentence. The Hipster With the Golden Ego, if you catch my drift.

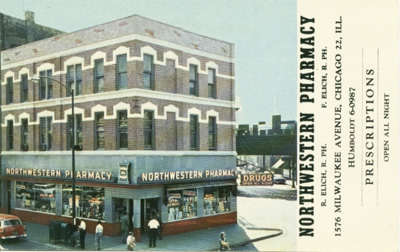

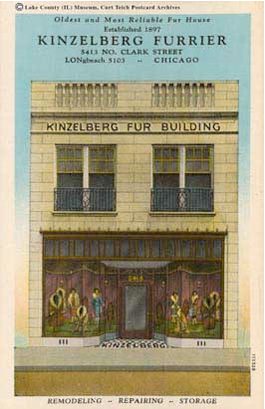

Lake County Museum, Curt Teich Postcard Archive. |

|

A somewhat undistinguished two story at 5413 N. Clark, this building is still around and is currently occupied by a hispanic restaurant, Ole Ole. All of the small details have been removed over the years, including the name at the top, to the tile inset of the name at the ground floor. The second story windows have been replaced, as have their balustrades. Most notably, the inset store window was replaced with something a little more up to date and conventional.

However, a faint ghost sign for Kinzelberg can still be (barely) seen on the building’s south wall. |

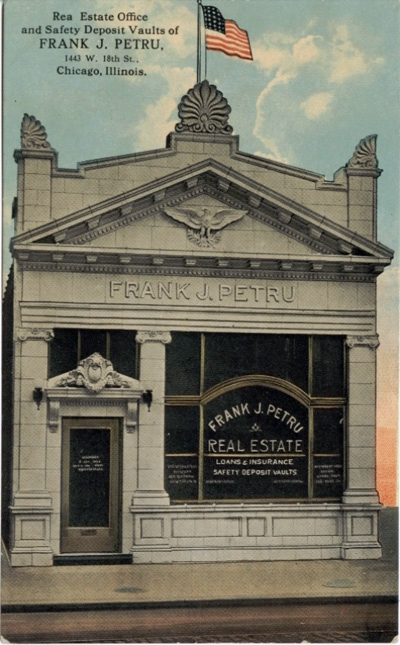

Left: Chicago History in Postcards.

This small office in Pilsen very closely resembles today its postcard view from yesteryear. Aside from two of those seashells missing, and a new door and window, it is otherwise intact. It is very likely that under the Libreria Giron sign, Frank J. Petru’s moniker is still there. There is definitely something to incorporating one’s name onto a structure using permanent material.

Something could be said for how this before and after view represents shifting demographics in Pilsen over the last century, but you probably already knew that. Its not very subtle.

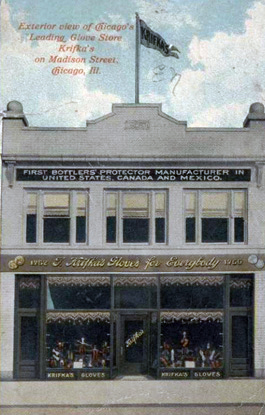

Chicago History in Postcards.

1952 W. Madison (left), and 2254 W. Madison (right), both long, long gone. Four observations – (1) What is a bottlers protector? (2) Are there any businesses still around that sell gloves exclusively? Has glove retailing been relegated to the Kmart/Nieman Marcus dichotomy? (3) That is quite an early automobile. Quite early indeed. (4) Yes, Monsieur Archambault, enough bunting, you’ve assimilated already.

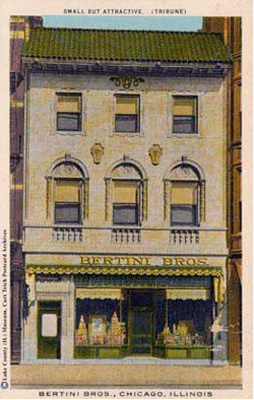

Left: Lake County Museum, Curt Teich Postcard Archives. Right: American Terra Cotta Company Photographs, University of Minnesota.

Designed by Michaelson & Rognstad sometime around 1923, this three story terra-cotta clad on Wells street still exists. Built in an Italian Baroque style for the Bertini Brothers company, it now houses a posh eatery – Crofton on Wells. Bertini occupied the location until the mid-1980s, at least.

Left: Illinois Historic Preservation Agency.

As for the architects, they are more well known for three excellent buildings in Chinatown; the Moy Association Building, the On Leong Building, and the Won Kow Building (below). They are also responsible for the excellent Art Deco style 7th Street Hotel. Many of their buildings were designed in all sorts of revival styles, and they are adept at expressing the ethnic identity of their clients.

Any car enthusiasts out there recognize this logo? It is a less detailed version of the biscione, a serpentine figure used in the city of Milan’s coat of arms, and more famously, on Alfa Romeo’s shield. It should be noted that this facade is in a pristine state, well-maintained, and un-modified since having been built.

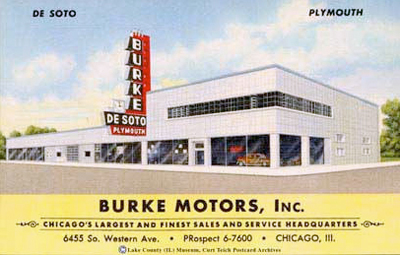

Lake County Museum, Curt Teich Postcard Archive.

Two Plymouth-DeSoto dealerships, which feature many contrasts. Northside, southside. Curved glass, flat glass. Horizontal sign, vertical sign. Rustic brick facade, white limestone facade. And so forth. Both of these buildings still stand; the Kedzie/Foster location is across the street from North Park college, and the last use of it that we’ve seen was as a college bookstore.

MSN Live Maps

Notice how the older half-section of this building was completely omitted in the postcard image. Infact, the postcard takes some liberties with regards to the placement of the windows. A good reminder that images don’t necessarily represent ‘real’ reality.

Left: Lake County Museum, Curt Teich Postcard Archive.

This was a fairly non-descript service station which, in being divided, re-facaded and repurposed, was made even more non-descript. It was difficult to identify this as the same location, but was made far easier by the position of the smokestack and glass roof at the top of the building. As opposed to the DeSoto postcard above, small details were portrayed accurately in this image.

Stony Island was an important pre-interstate arterial highway. When the Calumet expressway was built in 1955, it emptied onto Stony Island around 103rd (as it still does), pre-dating the connection to the then-non-existant Ryan expressway. Thus, there are many buildings along Stony Island that are either auto-related or are designed with auto access in mind.

Regarding the sign on the image at right, why would one name a business “Fleur-de-lis” and not include a fleur-de-lis on the front of the building?

Chicago History in Postcards.

Left: Lake County Museum, Curt Teich Postcard Archive. Right: MSN Live Maps.

Although in business at least until 1962, further information on E.C. Rieck Paint Co, unlike postcards, is scarce. The building was demolished at some point in the 1990s, and the foundation is clearly visible in the aerial view at right.

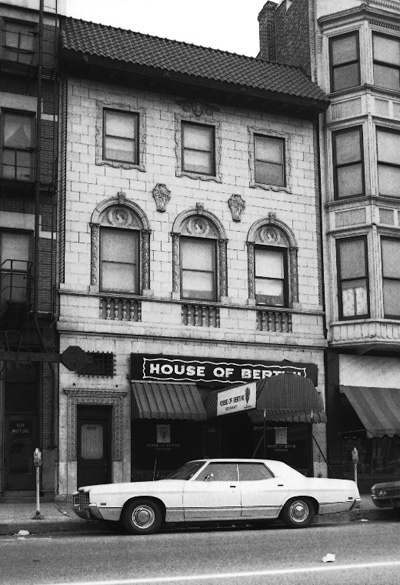

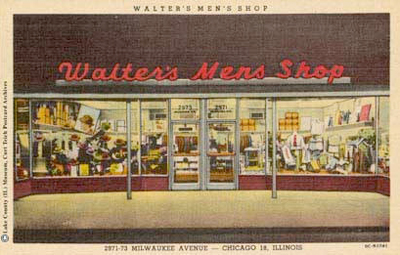

Lake County Museum, Curt Teich Postcard Archive.

Two long gone Logan Square storefronts. The ultra-Moderne Logan Bowl, built in 1940, was out of business by 1965, and was demolished less than five years later to make way for the Spaulding auxilary exit for the Logan Square subway station, which opened in 1970.

The taxpayer blocks of which Walter’s Men’s Shop was a part, was replaced with a Modernist bank in 1967.

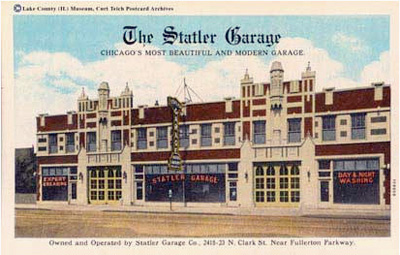

Lake County Museum, Curt Teich Postcard Archive. |

The postcard bills the Statler Garage as “Chicago’s Most Beautiful and Modern Garage,” which is a laughable statement eighty years later. With three levels of parking, it may be Chicago’s smallest elevator garage, but it is certainly not modern with a capital M. |

The Statler was built in an era when car ownership was still available mainly for the well-to-do. The Model A’s and Buick Sedans of the day required more frequent servicing than contemporary vehicles, and garages like the Statler were not just places to park for an hour, but full service and storage facilities. At some point in its history, it became more profitable to lease out the storefront space to other businesses, and the Statler became an interesting example of a store-and-flats, housing cars rather than people.

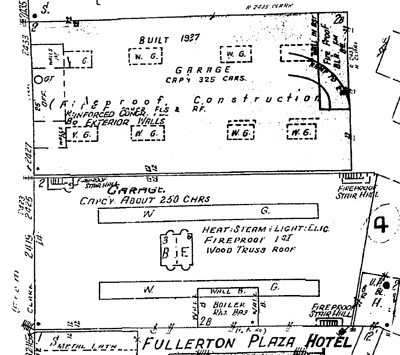

Left: Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1950. Right: MSN Live Maps.

The Statler (left image, bottom / right image, right) is adjacent to another garage, built in the same year. Interestingly, as clearly visible in both of these image, the adjacent garage is a ramp-type, while the Statler has an elevator. Elevators are generally used in garages which are more than five or six stories where property values are high.

The Statler today is so densely packed with retail, that one can barely tell it is still a parking garage. However, not far from its original function, it is once again filled with the automobiles of the well-to-do.

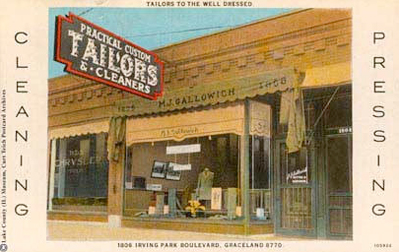

Lake County Museum, Curt Teich Postcard Archive. |

This store, located at 1806 W. Irving Park, which is on the north side of the street, between the Ravenswood ‘L’ tracks and the UP-North tracks, has been disgraced with a rather unfortunate facade job since at least the 1960s. The image below, from 1969, depicts this building to the far right of the image, behind the bus. This block of flats appears this way today. |

Tom’s Trolley Pictures, 1969.

Check out the Alpo ad on the side of the bus. 100% meat!

Lake County Museum, Curt Teich Postcard Archive.

Left: It seems the Bruhnke Brothers were peddling Silver Plume beverages, but we can find little else beyond the fact that they went out of business at some point between 1942 and 1955. The building no longer exists.

Right: One wonders what horrendous chemicals flowed behind this colorful window and handsome facade. Hopefully the site wasn’t terribly polluted because, guess what? Condozed.

Left: Lake County Museum, Curt Teich Postcard Archive.

Then: Scandinavian. Now: Yuppinavian. It is bittersweet!