One of the most unique bridges in Chicago still carries train traffic through the Bridgeport neighborhood. The history of the Chicago & Alton Railroad Bridge is intricately woven into the story of the neighborhood, the growth of the city, and the development of the Illinois & Michigan (I&M) Canal and the railroads as Bridgeport and Chicago became a key junction and national center for trade, transportation, and commerce.

A.T. Andreas, History of Chicago

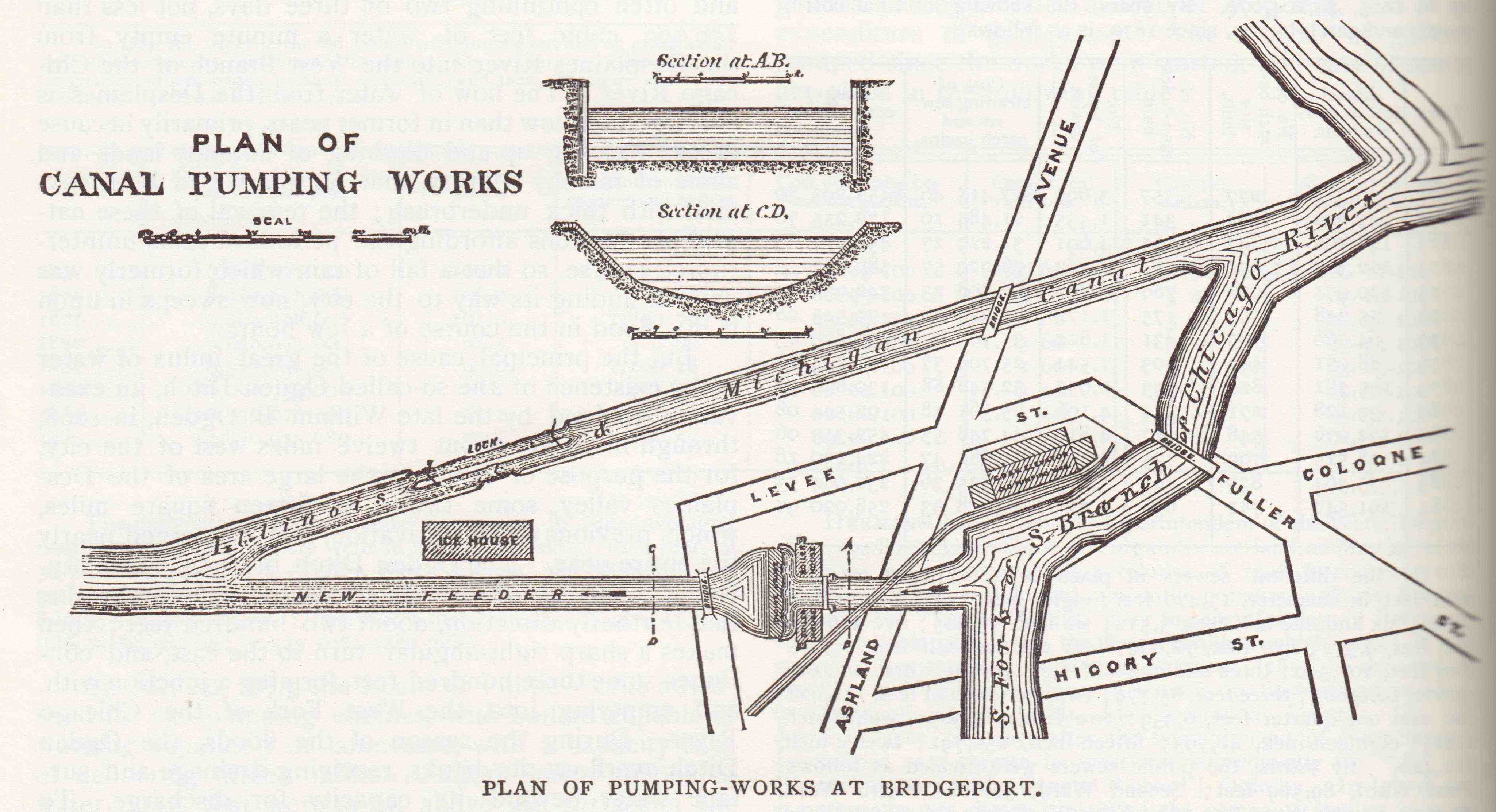

Early in Chicago’s history, the many bridges in the area, and particularly a low bridge (near South Ashland Street), prevented ships from entering the I&M Canal, and gave rise to the name Bridgeport. Early in Chicago’s history Leigh’s Farm was where, on April 6, 1812, Liberty White and Jean Baptiste Cardin were killed by marauding Winnebago. As the Indians approached, farmhand John Kelso (a former Army Private at Fort Dearborn) and 16 year-old John Leigh escaped by crossing the river under the pretense of tending cattle before fleeing to safety. Early white settlers later called the area “Hardscrabble.” This became a mostly Irish neighborhood of new immigrants attracted to the low-skill, low-wage jobs digging the I&M Canal. It was often the only work they could find, at a time when job postings often proclaimed “no Irish need apply.” In the map above from the late 1800s, the site of the Chicago & Alton Railroad crossing of the South Fork is a block-and-a-half south of Hickory Street. It should also be noted that Fuller Street as shown on the map was previously known as Bridge Street during the 1840s, 50s, and 60s.

Patrick McBriarty

Constructed nearby in 1906, the Chicago & Alton Railroad Bridge crosses Chicago’s Bubbly Creek next to its relatively new neighbor, the CTA Orange Line, which ironically opened in 1993 on Halloween Day. The unique Chicago & Alton Bridge was designated a Chicago Landmark on December 12, 2007. It is a Page bascule design (one of four ever built), and it crosses the South Fork of the Chicago River’s South Branch, just below the split into its South and West Forks.

Wikipedia

The waterway crossed by the Chicago & Alton Railroad Bridge is commonly referred to as Bubbly Creek because of the methane and hydrogen sulfide gas that still bubbles to the surface from the decay of organic matter on the river bottom. This is a visible remnant of the South Fork’s use as a waterway once connecting to a mile-long, east-west canal at 39th Street serving the Union Stock Yards. The meat packing businesses in the area used the stream for shipping and to dump waste and remains. As a result the condition of the river in the area was once so bad chickens and even drunks were reportedly seen walking on water – mistaking the crusted surface for dry land, often with disastrous results.

On October 8, 1891, a boiler explosion on the tugboat C. W. Parker killed her crew of three instantly, and four innocent bystanders on the riverbank. The river, normally a reliable water source for the boilers on steam driven Great Lake ships and tugs, was so contaminated that the heated organic matter spawned a dramatic increase in pressure causing the plate-iron boiler of the Parker to explode violently, killing seven people. This incident occurred just a few hundred yards from the site of the Chicago & Alton Railroad Bridge.

Historic American Engineering Survey (HAER) Photograph, Library of Congress

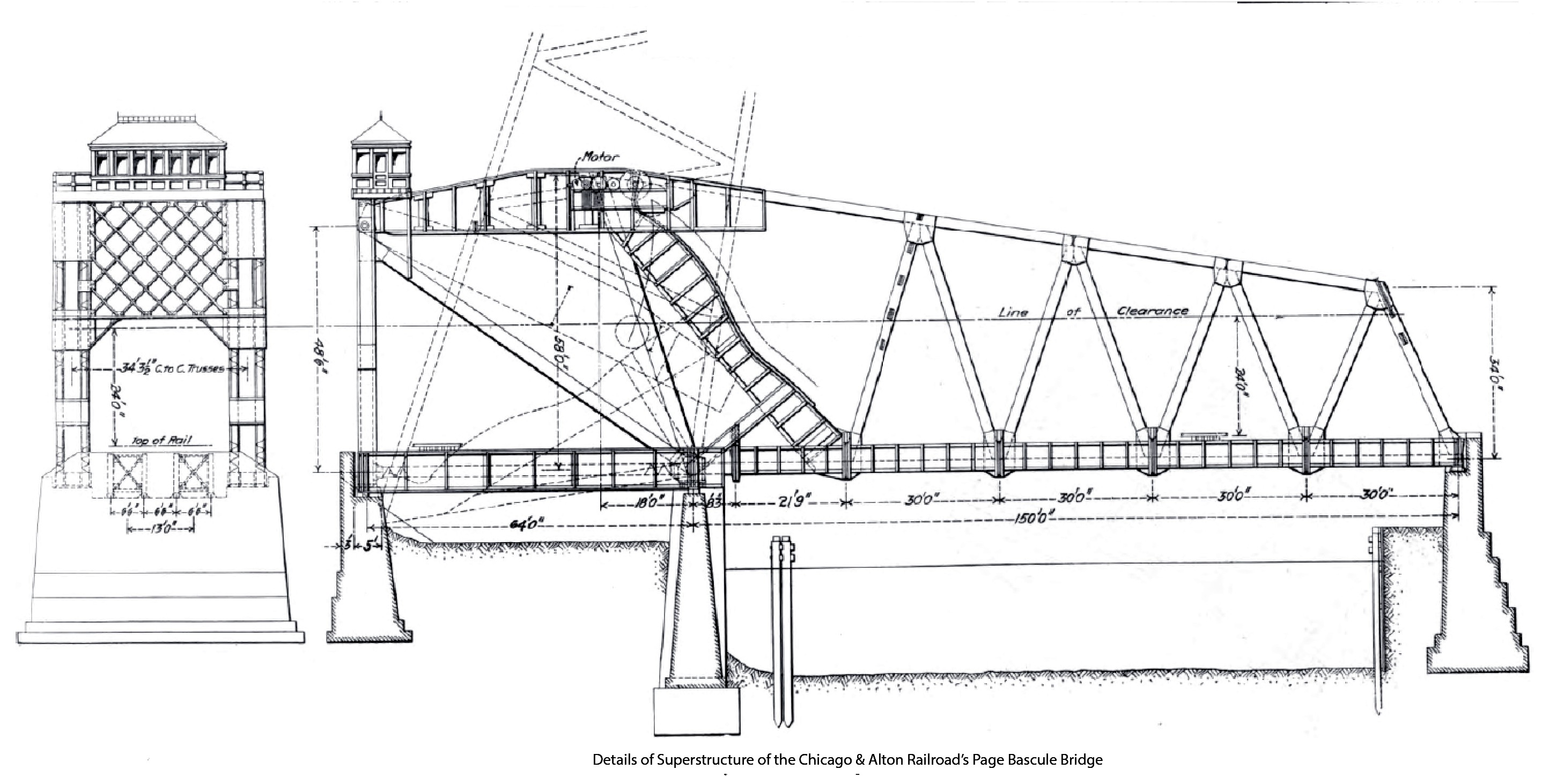

In 1906, Chicago & Alton Railroad Chief Engineer W. D. Taylor and Assistant Engineer A. R. Ekstrom oversaw construction of this bridge to replace an old swing bridge. Three railroad companies, the Chicago & Alton; Illinois Central; and Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, financed the $165,000 bridge, which was also used by trains of the Wisconsin Central through an arrangement with the Illinois Central Railroad. The new single-leaf, Warren-truss Page bascule was designed by independent consulting engineer William M. Hughes of Chicago. It was capable of carrying two trains driven by engines weighing a maximum of 192.5 tons each, followed by rolling stock of up to 5,000 lbs per linear foot.

The gearing and operating motors were supported on longitudinal girders arranged to help counterweight the bridge. Further counterweights were made up of cast-iron blocks attached to the steel plate approach structure. In this manner counterweighting of the bridge was integrated into the bridge superstructure and it opened similar to stepping on a crowbar. This gave the bridge a much cleaner, albeit chunky appearance and kept the counterweights above grade, as compared to the Strauss heel-trunnion or vertical-lift bridges with their large suspended concrete counterweights. In addition, it avoided the extensive counterweight pit and foundation configurations of the below-grade counterweight bridges of the more common Strauss and Chicago-type fixed trunnion bascule bridges on the Chicago River. This Page bascule bridge was operated by two 125-h.p. railway motors activated using a train series-parallel controller inside the bridge house situated above the bridge’s western approach, supported by the four vertical end posts.

Railroad Gazette

Engineer John W. Page was born in 1865 and graduated with and engineering degree from the University of Illinois in 1892. His first job in Chicago was as a sanitary engineer for the Columbian Exposition in 1893, and afterward worked for the Sanitary District on excavation of the Sanitary & Ship Canal to reverse the Chicago River. Between 1901 and 1903 Page was granted three different bascule bridge patents. However, his greatest success was the invention and development of the dragline method of excavation, which helped spur the creation of the contracting firm Page and Shnable (1900-1908) in partnership with Emile Shnable, and later the founding of the Page Engineering Corporation in 1912.

Patrick McBriarty

Page & Schnable received a patent royalty on the Chicago & Alton Railroad Bridge, a 150-foot long, single-leaf, double-track bridge, replacing an 1880s bobtail swing bridge. These and earlier bridges at this location helped to give the Chicago neighborhood of Bridgeport its name. The new bridge was a significant improvement crossing the waterway at a skewed angle, it offered a clear channel for navigation of 100 feet. The Page bascule bridge was chosen because it was deemed most economical in cost of construction among the competing design proposals. The project started in March 1905 and maintained railroad traffic over the old bridge, while the new bridge was erected in the upright position. The Thomas Phee Company of Chicago completed the substructure, removal of the old, dredging the channel to 21-foot depth, and driving of timber protection for the new bridge at an approximate cost of $50,000. The Kelly-Atkinson Construction Company of Chicago erected the superstructure, which was fabricated at the American Bridge Company’s Lassing Plant (once located on the corner of Clybourn and Wrightwood Avenues) in Chicago. G. P. Nichols & Brothers of Chicago installed the bridge controls and electrical equipment, which included a novel four-light bridge position indicator, an all-electric interlocking plant, magnetic brakes, and wedge locks on both lower cords to secure the bridge with the abutment.

Trains were temporarily detoured during the cutover. The old bridge was dismantled, the new bridge lowered, decking completed, final tracks laid, and the first train crossed the new structure just 24-hours and 50-minutes later. Prior to the cutover, bridge operation was tested by moving it back and forth through the top end of its arc without interfering with rail traffic or operation of the swing bridge. In 1959 the South Fork of the South Branch was re-classified as a non-navigable waterway and the bridges crossing the stream were allowed to be fixed in place. Since 1999, the Chicago & Alton Railroad Bridge has been owned and maintained by the Canadian National Railway with its acquisition of the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio Railroad.

Patrick McBriarty

Beyond the Chicago & Alton Railroad Bridge, three other Page bascule bridges were built. They were the South Ashland Avenue Bridge (1902-1936) in Chicago over the West Fork of the Chicago River’s South Branch, the Third Street Bridge (1906-1933) over Mission Creek in San Francisco, and the Monon Railroad Bridge constructed in 1906 over the Grand Calumet River in Hammond, Indiana (above). The Monon Railroad Page bascule was built in anticipation of the Grand Calumet River being made navigable, however those plans faded and it is now little more than a stream most of the year. The bridge and rail line has since been decommissioned, the railroad tracks removed, and one wonders if the operating equipment and counterweights were ever actually installed. However, the bridge clearly sports the telltale curved steel rack of the Page bascule design. A newer double-track rail line approximately two-hundred feet to the west now crosses the Grand Calumet River via a gravel embankment pierced by three six-foot diameter corrugated steel culverts. Between January and July of 2015, a scrapper, Kenneth Morrison, owner of the admitted to dismantling and destroying this bridge leaving it partially dismantled in the river. Allegedly later that spring he returned to remove the rest of the bridge. In February he responded to an Northwest Indiana Times inquiry, “I myself state that this property is abandoned. It’s like a shipwreck. If a ship sinks, that’s abandoned, and it’s fair game.”

As late as July 2016, it was reported an investigation was being undertaken by the U.S. Attorney’s Office of the incident. In 1995, Morrison owner of the LaSalle Central Contracting was convicted for improperly discharging 2,000 gallons of waste oil into the Schuylkill River in Pennsylvania and another 3,000 gallons into the ground after a salvage of a metal tank containing 100,000 gallons of oil and tar in 1991. The scrap value of the Monon bridge was estimated to be $340,000. Morrison could produce no permits and had approached the City of Hammond as early as 1991 and again in October 2014 and told by authorities both times the bridge could not be scrapped.

Unlike these other examples, the Chicago & Alton Railroad Bridge remains the only Page bascule bridge still in use anywhere in the world. The bridge house and operating equipment have been removed as this single-leaf bridge no longer opens and is treated as a fixed span; however it still carries rail traffic across this once-navigable waterway. As an interesting juxtaposition, the bridge, built at a time of horse and carriages, now carries fiber optic cable to connect communication and data across the river.

Engineering World and Contracting News, New Double-Track Railroad Bridge Over the Chicago River. July 10, 1907, p. 30-32.

Engineering Record, Page Bascule Bridge on the Santa Fe improvements in San Francisco. New York, May, 1906, pp. 618-9.

Keagle, Lauri Harvey, Man who demolished Hammond bridge defends actions, Northwest Indiana Times, February 4, 2015.

Keagle, Lauri Harvey, State cites Whiting man in Hammond bridge demolition case, Northwest Indiana Times, July 29, 2015.

National Park Service, Historic American Engineering Record, Chicago and Alton Railroad Bridge, HAER No. IL-104, 1992.

Pete, Joseph, Scrapper who took Monon Bridge was convicted for oil spill, Northwest Indiana Times, April 4, 2015.

Proceedings of the Second Pan American Scientific Congress, Washington D.C., Dec. 27, 1915 – Jan. 8, 1916, Government Printing Office, 1917, p.309.

Schreiber, George, Engineer-Inventor Page is Active at 96, Chicago Tribune, January 12, 1964 pD7.

- Bridge Out For Good

- The 12th Street Bridge That Never Was

- Grove Street

- Railroads and Chicago Swing Bridges

- South Western Avenue Improvement