While it is easy to overlook the railroads in Chicago nowadays, this city has been a major rail hub if not the most important railroad city in the nation and the world for more than 150 years. As with any road — rail or otherwise — to be useful for Chicago it must invariably cross the Chicago River. Chicago’s first railroad — the Galena & Chicago Union (G&CU), founded in 1848 — was responsible for the city’s first depot and first railroad bridge. The growing city divided by the busy waterway would make the drawbridge a necessity, and the swing bridge, now nearly forgotten, was for decades the most common type of bridge crossing the Chicago River.

Yesterday and Today, a history of the Chicago and North Western Railway System, Stennett, William H., Chicago & North Western Railway, 1910

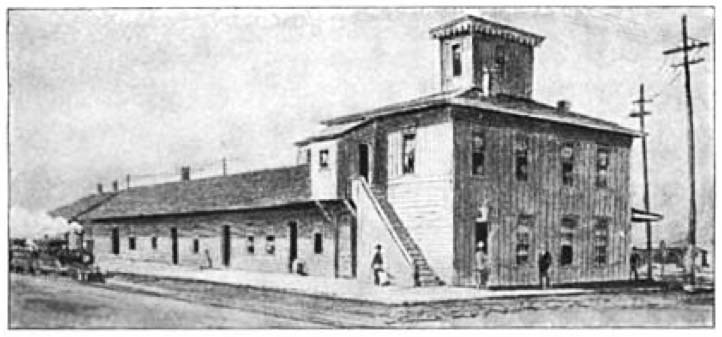

The G&CU railroad originally operated from Chicago to Elgin, Illinois and points west from an engine house and shop on the west side of the North Branch of the Chicago River. In 1851 the expanding railroad purchased Block No. 1 (of the original town of Chicago) bounded by Dearborn, Kinzie, State, and North Water Streets, north of the river. It was here in 1851 that a depot and general office building, engine/blacksmith house, and car shop were constructed. Today Block No. 1 is most easily identified by the landmarked Chicago Varnish Building, built in 1895, and home to Harry Carry’s Restaurant on the northwest corner of the block.

Yesterday and Today, a history of the Chicago and North Western Railway System, Stennett, William H., Chicago & North Western Railway, 1910

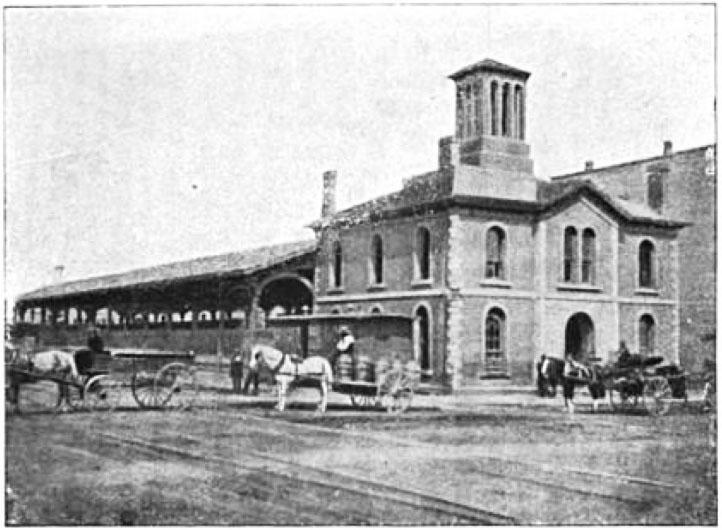

In 1851 the G&CU exchanged a strip of land from Block No. 1 for a portion of Block No. 5. This new site became home to a second G&CU passenger station at Wells Street, completed in 1853, at the corner of Wells and Kinzie Streets. Chicago’s first railroad bridge was built the year prior for the G&CU by Jenks D. Perkins. This pontoon swing drawbridge crossing the North Branch of the Chicago River connected the new depot and passenger stations to the western railway. The site is identified by the open railroad bridge standing in the air today next to Kinzie Street, which was the location of Chicago’s first railroad bridge.

Yesterday and Today, a history of the Chicago and North Western Railway System, Stennett, William H., Chicago & North Western Railway, 1910

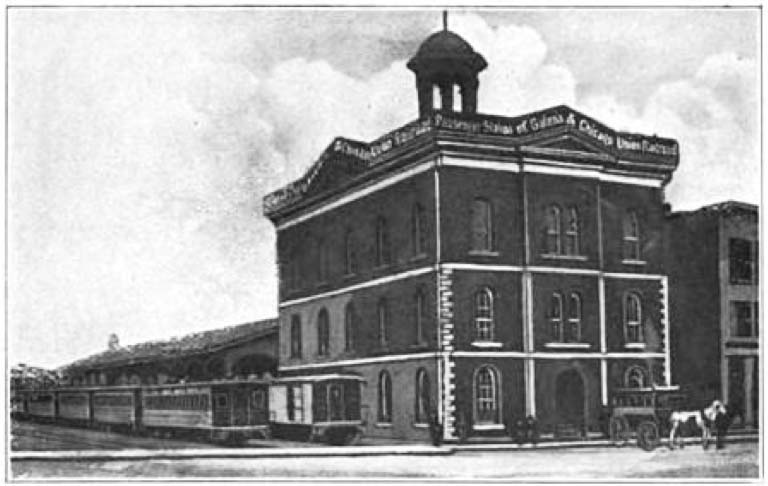

In 1862-63 in conjunction with the raising of the street grades in the area, the Wells Street Station was renovated, lengthened, and a third story was added. Then in June 1864, the G&CU was consolidated with the Chicago & North Western Railway (C&NW) and headquartered at the Wells Street Station in Chicago. The station was destroyed in 1871 by the Great Chicago Fire and replaced by a temporary wood structure, until the C&NW built the grand, red-brick, clock towered Wells Street Station, which opened on May 23, 1881. This station was razed in 1911, after a new Chicago & North Western (C&NW) Terminal was built at 500 West Madison, between Clinton and Canal Streets on the west bank of the Chicago River’s South Branch. The site of the old Wells Street Station is now occupied by the Merchandise Mart, which opened in 1930, and was constructed for Marshall Field & Company.

Left: Detroit Publishing colorized 1898 photograph from the Library of Congress Right: Library of Congress, taken by Mellen Photo Co.; July 15, 1912

In 1984 the C&NW Terminal at 500 West Madison was razed and the lower floors of the new 42-story, blue, glass and steel Citicorp Center became the train station. The adjoining train shed attached to the station was purchased by Metra in 1991 from the C&NW and a four-year $138 million rehabilitation of the structure followed. In 1995 the C&NW merged with the Union Pacific Railroad and two years later the station was renamed the Ogilvie Transportation Center after long-time railroad advocate Richard B. Ogilvie, who was Governor of Illinois from 1969-73. In 1979 Ogilvie was appointed Trustee of the Milwaukee Road after its bankruptcy and oversaw its reorganization, and its purchase by the Soo Line Railroad.

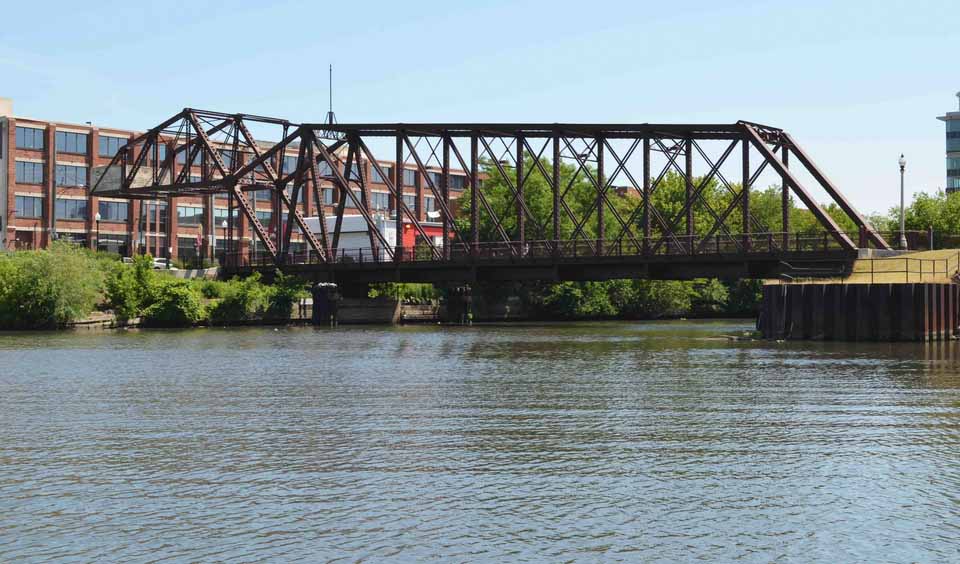

© Patrick McBriarty

The railroad bridge at Kinzie Street is no longer used and was left open after the last rolls of newspaper were delivered to the old Chicago Sun-Times production building on North Wabash Avenue in 2001. Newspaper production was relocated to a new south side production facility on South Ashland Avenue and the old Sun-Times site is now home to the Trump Tower. The Sun-Times was the last commercial customer on this railroad spur running along the north bank of the Chicago River. The bridge’s now-disused status contrasts drastically with the first month the bridge opened in September 1908, when it lifted 983 times and carried many freight and passenger trains per day.

| Opened | Bridge Type | Constructed By | Cost | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1852 | Pontoon bridge | The Galena & Chicago Union Railroad | $20,000 | Removed in 1864 |

| March 1864 | Swing bridge | The Galena & Chicago Union Railroad | Unknown | Removed in 1879 |

| 1879 | Swing bridge, all steel | Chicago & North Western Railroad Co. | Unknown | Removed in 1898 |

| 1898 | Swing bridge, all steel | Chicago & North Western Railroad Co. | Unknown | Ordered removed by Secretary of War in 1905 |

| Sept. 9 1908 | Strauss heel trunnion bascule, single leaf | Kelty-Atkinson Construction Co. (superstructure) Great Lakes Dredge & Dock Co. (substructure) | Unknown | Open since 2001 |

© Patrick McBriarty

Surprisingly, a few swing bridges still remain in Chicago over the Chicago River and the Sanitary and Ship Canal. The best-known swing bridge in Chicago is at North Avenue over the North Branch Canal connecting the northern tip of Goose Island. The bridge is the only railway connection with Goose Island, and is still used for the occasional freight shipment. It was granted historic landmark status in December 2007, and received a $2.5 million rehabilitation over the next two years, which included the addition of new decking and lighting to allow bicycle and pedestrian use. It is believed this work was influenced by the 2005 development of the $50 million Wrigley Global Innovation Center on the north end of Goose Island. The bridge originally constructed in 1902 by the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway is a bobtail swing bridge known as the Z-2 or Cherry Avenue Railroad Bridge. The 230-foot long asymmetrical structure is referred to as a bobtail swing because of the shortened north end with its concrete counterweight. The counterweight balances against the heavy steel truss spanning the waterway. By adding the counterweight the center of gravity of the bridge is positioned above the turntable upon which it rotated. Often obscured by weeds, the supporting turntable is situated on the north side of the waterway.

From 1890 until the 1990s the North Branch Canal was considered a navigable waterway and the federal government required bridges crossing the canal to be movable. To open the Z-2 Bridge swung to the east leaving the entire width of the canal open to ship traffic. After the U.S. Coast Guard relinquished the navigational requirement on the canal in the 1990s the bridge was fixed in place and no longer opens. This bobtail swing bridge replaced the wood and iron swing bridge built here in 1882. This first railroad connection with Goose Island was a Howe truss superstructure rotating on a center-pier turntable in the middle of the waterway. Although swing bridges were usually replaced by newer bascule bridge designs (which opened vertically), at this location the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway, known for constructing its own bridges, opted for the alternative bobtail swing design. It was a simple, low cost, proven design, and could be built without paying additional patent royalties or outside contractors. These considerations must have outweighed the significant advantages of bascule designs — a smaller footprint, reduced land requirements, and dockage next to the bridge.

Excerpt of the Smoke Abatement Maps of 1915; additional graphics added by the author

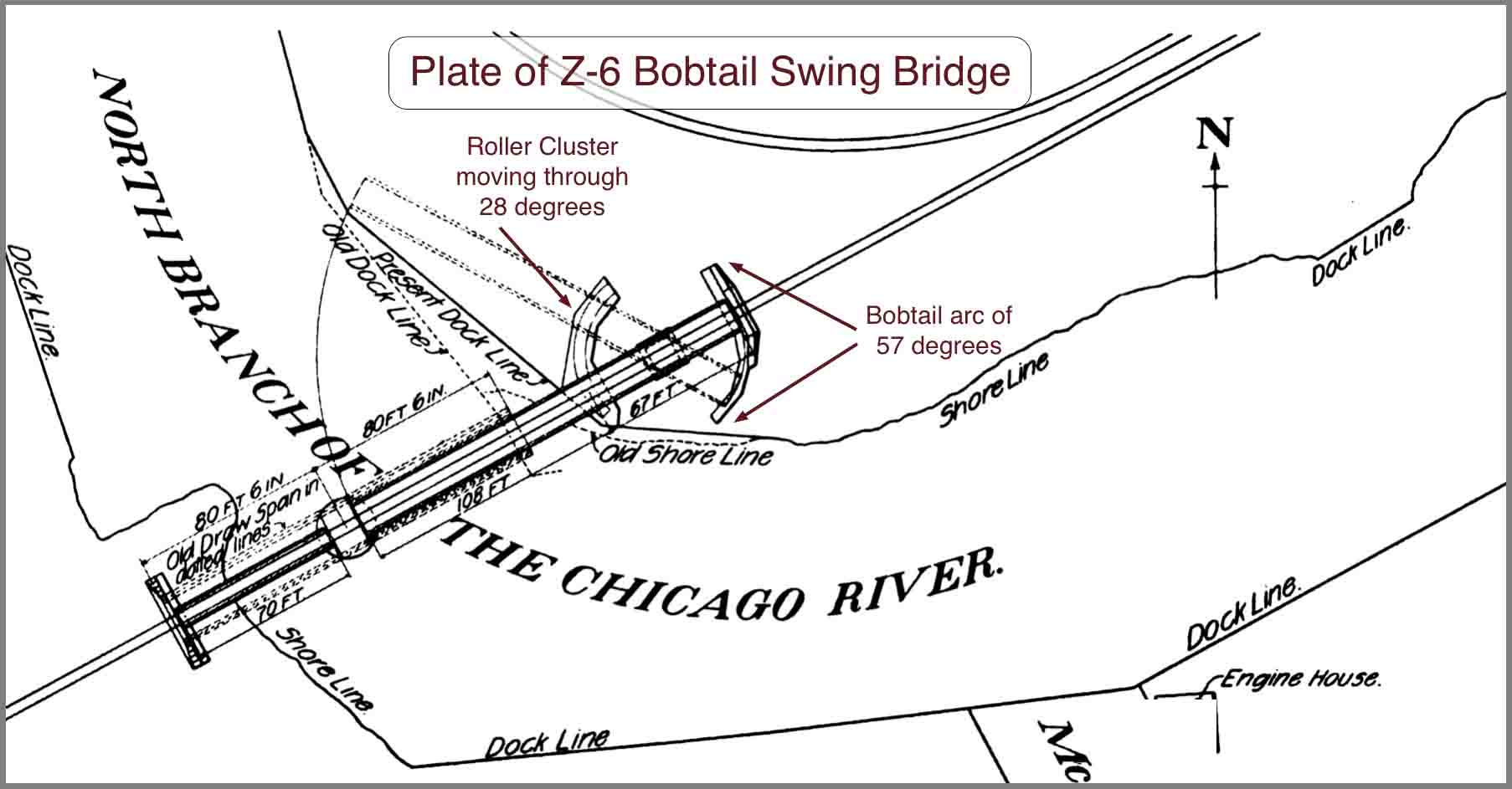

A second, not nearly as well known swing bridge exists about a mile north of the Z-2 Bridge at a bend in the North Branch roughly one block south of Cortland Street. Built in 1899 also by the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway, this bobtail swing bridge is still operable due to its very low river clearance. Usually left in the open position, it is still used to move train carloads of recycling from scrap metal dealers on the east side of the river. This steel plate-girder swing bridge is unique and operates on an abbreviated turntable composed of a cluster of rollers moving in a 28-degree arc and rollers under the bobtail-end moving through 57 degrees. Normally open, the bridge rests entirely over land on the east bank of the river. Though not obvious from its profile, between the plate girder sides of the bridge its short tail-end holds 56.65 tons of iron counterweights. At just over 175-feet long, this may be the longest plate-girder swing bridge ever built, as established engineering standards generally limit such spans to 150 feet. However, the unsupported section of the Z-6 Bridge spanning the river is only 141-½ feet long.

Left: © Patrick McBriarty Right: Historic American Engineering Survey (HAER) Drawing, Library of Congress; additional graphics added by the author.

HAER Survey Photograph, Library of Congress

The longest of seven surviving swing bridges crossing the Sanitary and Ship Canal is the 479-½ foot long swing bridge just east of Kedzie Avenue near 35th Street. This double-track railroad bridge is representative of the type of railroad swing bridges found around the nation in the late-1800s and early-1900s. Resting on a limestone center pier in the middle of the canal, the span was constructed in 1899 by the Sanitary District of Chicago (now the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago) for the Chicago, Madison, & Northern Railroad. The bridge was needed to continue the railroad’s right of way and allow construction of the Sanitary and Ship Canal, which opened in 1900, reversing the flow of the Chicago River away from Lake Michigan. The symmetrical pin-connected steel structure while in operation was entirely supported by a 28-foot diameter turntable resting on the bridge center pier. Prior to World War II the bridge was treated as a fixed span (as it is today), but the anticipation of significant Great Lakes shipbuilding in 1942 caused the U.S. Navy to let a contract to install the necessary operating equipment to make the bridge operational. It is believed the bridge was last opened in 1953 for delivery of the final Navy minesweeper ship built at the H.C. Grebe and Company’s shipyard on the North Branch of the Chicago River to the Gulf of Mexico. The Illinois Central Gulf Railroad now owns and maintains this bridge.

HAER Survey Photograph, Library of Congress

Sharing a similar history, the Illinois Northern Railroad Swing Bridge near Central Park Avenue and 35th Street was also built in 1899 by the Sanitary District. The Keystone Bridge Company constructed the bridge, while the 372½ foot long superstructure was fabricated by the Carnegie Steel Company. This two-track railroad bridge is also a steel pin-connected, Pratt through-truss, swing bridge. Supported in the middle of the canal by a center-pier and turntable, the Sanitary District held off installing the remaining operating equipment until necessary. It was not until American involvement in World War II that operation of this swing bridge was needed to take advantage of Great Lakes shipbuilding. So in 1942 the U.S. Navy contracted the final conversion to a movable bridge, which was overseen by the railroads and paid for by the Navy. This opened the Sanitary and Ship Canal to war ships, allowing safe delivery from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, so as to avoid the risk of attacks by German submarines patrolling the Atlantic coast.

HAER Survey Photograph, Library of Congress

The only other swing bridge in Chicago is the Atchinson, Topeka, & Santa Fe Railroad Swing Bridge crossing the Sanitary Canal at West 46th Street. Also built by the Sanitary District and converted to a swing bridge by the U.S. Navy in 1942, it carried four tracks over the waterway. When built in 1899 there were very few cases where a single two-truss bridge carried four railways; normally a three-truss superstructure was employed. The bridge carried two tracks down the middle and a track cantilevered off each side of the bridge. The outside railway tracks have since been abandoned and removed from the bridge. This sturdy 1,346-ton bridge is designed to carry at least 4,200 lbs per linear foot over its entire length on each roadway (or about 700 tons per roadway). At just over 334-feet long and 54-feet wide the bridge was designed to safely support any combination of trains crossing the bridge at the same time.

Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway, Bridge No. Z-2, Historic American Engineering Record, No. IL-143, U.S. Department of the Interior, Historian: Justin M. Spivey, 2001.

Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway, Bridge No. Z-6, Historic American Engineering Record, No. IL-163, U.S. Department of the Interior, Historian: Justin M. Spivey, 2001.

Historic Railroad Bridge Survey, City of Chicago, Department of Transportation, Bureau of Bridges and Transit, Johnson Lasky Architects, 2001

Various Articles, Chicago Tribune Historical Archives (1849 to 1988)

Yesterday and Today, A History of the Chicago and North Western Railway System, Chicago and North Western Railway Company, William H. Stennett, 1910.

- Bridgeport’s Chicago & Alton Railroad Bridge

- South Western Avenue Improvement

- Bridge Out For Good

- The 12th Street Bridge That Never Was

- Chaddick Institute Terminal Town Walking Tour on Sunday, October 27, 2019