On the evening of July 30, 1939, Nancy Froemming “and her ambition” boarded a train in Milwaukee bound for Chicago. Miss Froemming — who thought that she “could sing with the best of them” — had decided that Milwaukee was too small of a town for her nascent singing career and set her sights on the hustle-and-bustle of Chicago. So off she went. There were only two problems with Miss Froemming’s plan: she was 13 years old, and the train she boarded was a freight line — the Bloomingdale Line. Upon alighting at Western Avenue, instead of booking a gig at the Cloister Inn or the Sunset Cafe, Miss Froemming was booked at Juvenile Hall.0.1

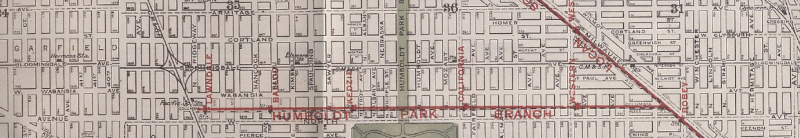

Long before it was ever thought of as a trail, the Bloomingdale Line — as it was sometimes known — hauled freight (and, it seems, one young girl’s ambition) for the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific Railroad Company, the storied “Milwaukee Road.” The Bloomingdale principally functioned as a connecting line used by freight trains between the north side of Chicago and the railroad’s yards at Galewood and Bensenville.0.2 But perhaps more fundamentally, the branch was a link to the rest of the country; the trains that traversed the Bloomingdale could access the St. Paul’s sprawling, nationwide rail network.

Left: Terence Banich. Right: Chicago Switching.

Left: Terence Banich. Right: Chicago Switching.

While the plans to convert the Bloomingdale’s derelict right-of-way into a linear park have united Chicago’s citizens, government and businesses behind an ambitious urban-renewal project, the citizens of late 19th and early 20th century Chicago angrily — and even violently — protested the railway’s intrusion into their communities. Originally built at-grade (i.e., street level) down the middle of Bloomingdale Road (now Avenue) — which was then, as now, surrounded by residences — neighbors did not appreciate the Bloomingdale Line’s negative effect on their property values, not to mention the perpetual injuries and deaths caused by the line’s trains passing through unguarded crossings.

Eventually, the city applied pressure on the St. Paul (as it was colloquially known) and in 1910 passed an ordinance requiring the railroad to elevate the Bloomingale between Ashland Avenue and Lawndale Avenue. The track-elevation project, thrust upon a recalcitrant railroad, became an engineering marvel in its own right. Several engineering and other construction trade publications of the era praised the railroad engineers’ techniques and efficiency, which resulted in the line’s elevation on schedule.

Archives of the Majestic Wood Carving Company Archives of the Majestic Wood Carving Company

The Colonial Chair Company touts its proximity to, and switch track connection with, the Bloomingdale Line.

|

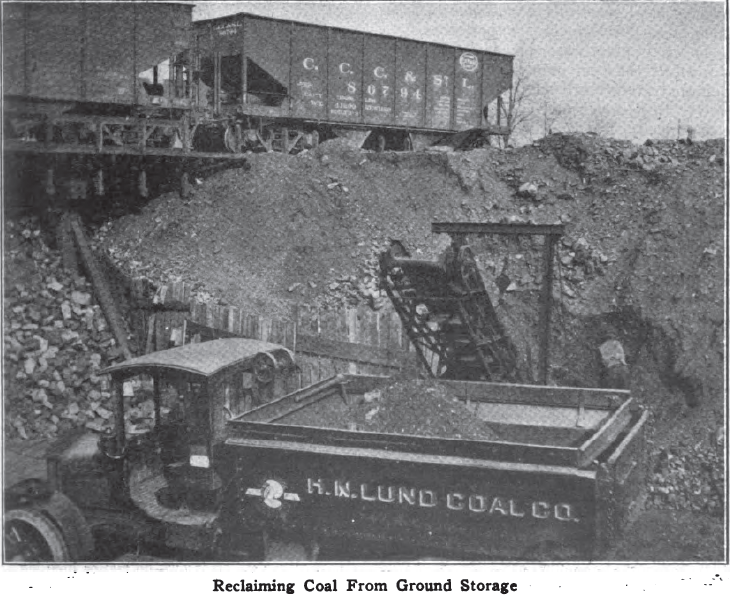

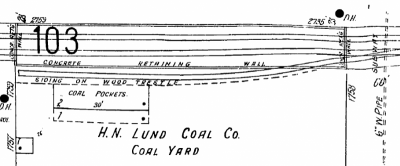

During its heyday, the Bloomingdale Line became the backbone of an industrial and manufacturing corridor that developed around it. In fact, the story of the Bloomingdale Line is very much the story of the companies that situated themselves along its route, many of whom depended on it as their principal link to interstate commerce. But the Bloomingdale Line suffered the same fate as did the rail industry generally — it yielded to the automobile. The industrial concerns that once maintained physical connections with the Bloomingdale Line (called “switch tracks” or “side tracks”) as their primary method of receiving and delivering goods increasingly and then totally turned to interstate trucking as their new link to the rest of the United States.

Meanwhile, Chicago changed. The manufacturers and industries that once surrounded the Bloomingdale Line folded or relocated, and over time the city rezoned their former locations for residential use. Finally, in 2001, after teetering on the edge of complete disuse for decades, the Canadian Pacific administered the coup de grace when it severed the Bloomingdale Line’s connection with the rest of the country. A forlorn reminder of the industrial Chicago of yesteryear, the Bloomingdale Line awaits transformation into the Bloomingdale Trail to again serve the citizens of Chicago.

This article is not intended to be a history of the Bloomingdale Line; that has been covered elsewhere.

Instead, the author examines how the Bloomingdale Line interacted with and affected the lives of Chicago citizens and businesses during its time in service. To that end, Part I attempts to put the remainder of the article in context by discussing the Bloomingdale Line’s establishment, the community’s vehement opposition to its presence during the first 40 or so years it existed and its eventual elevation. Part II is really the heart of the matter. In that section, the author examines how the Bloomingdale Line was, for many years, an integral part of the daily operations of many industrial and manufacturing businesses that existed next to the railway. To illustrate the point, the author profiles seven companies that were adjacent to the Bloomingdale and used it for shipping and receiving. Finally, Part III is essentially a coda reflecting upon the Bloomingdale Line’s disuse and abandonment.

The story of the Bloomingdale Line begins in 1857, a mere 20 years after Chicago became a city. The area that would one day be home to the Bloomingdale Line was still rural. During that year, however, a highway commissioner of the Town of West Chicago named August Steinhaus ditched and graded a certain street called “Bloomingdale road.”1.0 Thus, the street we know today as Bloomingdale Avenue was born. Ever since, Bloomingdale has continuously remained a public thoroughfare.1.1

Several years later, a large railroad company made a grandiose plan to connect Milwaukee and Chicago via rail. In 1871, the Wisconsin Union Railroad Company obtained a permit to build a rail line from Milwaukee to the Wisconsin-Illinois state line. That same year, the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway of Illinois was organized for the purpose of constructing the rail line from Chicago to the Illinois-Wisconsin state line.1.2 On January 1, 1873, both aforementioned railroad companies transferred their right, title and interest in the new tracks between Milwaukee and Chicago to the Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway Company,1.3 which changed its name the following year to the one that would endure for decades: “Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway Company.”1.4

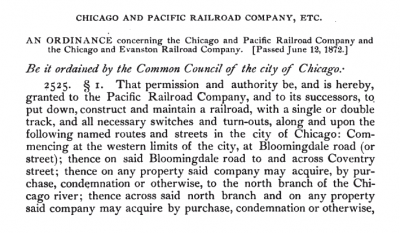

Left: David Rumsey Map Collection. Right: Special Laws and Ordinances of the City of Chicago §§ 2525-2532 (1881).

Left: David Rumsey Map Collection. Right: Special Laws and Ordinances of the City of Chicago §§ 2525-2532 (1881).

Around the same time, the City of Chicago allowed a different railroad company to build a line along Bloomingdale. On June 12, 1872, the City Council passed an ordinance authorizing the Chicago and Pacific Railroad Company to construct and maintain a railroad with single and double tracks on Bloomingdale.1.5 (Note the use of the word “on”: the Bloomingdale Line was originally built at grade level. More on that later.) The second track was apparently not laid until 1886.1.6 In April 1880, as a result of a financial panic and a protracted legal battle, the St. Paul assumed control over the Chicago and Pacific Railroad Company’s assets, including the Bloomingdale Line.1.6.1 (Details about those events, as well as other aspects of the Bloomingdale Line’s early operations (including passenger service), can be found in Ted W. Pannkoke’s carefully researched analysis of this subject.)

Suffice it to say, the community surrounding the new rail line did not welcome it with open arms. Opposition to the Bloomingdale Line began immediately. The month before the City Council passed the ordinance allowing the Chicago and Pacific to build along Bloomingdale, several residents of the 15th Ward gathered one Thursday evening (a gentleman named George Margetts presided) to protest the then-proposed right of way.

Chicago Tribune, May 4, 1872, pg. 4 |

The group eventually adopted a resolution declaring, in part, that installation of the railroad tracks would cause “great damage … to the surrounding property” and “obstruct[] … schools and churches in the neighborhood,” and requesting that their alderman employ his “utmost endeavors” to stop the ordinance from passing.1.7

But alas, the ordinance passed and construction began. Several Chicagoans filed lawsuits in response. For example, one Henry Francis, a resident along Bloomingdale road, sued the Chicago and Pacific Railroad and demanded an injunction to halt construction, alleging that he received inadequate compensation for the railroad’s occupancy, and that his property was “damaged” under the Eminent Domain Clause of the Illinois Constitution of 1870. He ultimately lost because he could not prove his property was worth less as a result of the railway.1.8 Also aggrieved, a resident named Catherine Boettcher also tried to enjoin construction of the Bloomingdale Line, claiming that the railroad’s laborers were unlawfully entering upon and damaging her land.1.9 The resolution of Ms. Boettcher’s case is not known; presumably, it was settled. Obviously, neither plaintiff succeeded in permanently enjoining the railroad’s construction.

Chicago Tribune, June 8, 1874, pg. 5 |

The clock was ticking. The 1872 ordinance gave the Chicago and Pacific only two years to lay its tracks along Bloomingdale. As it turned out, in June 1874, the railroad was trying to beat the buzzer. The Bloomingdale Line was complete except for a section near Goose Island. But because there was “great opposition” among property owners to expansion of the railroad in this area, the Chicago and Pacific decided to be crafty: it commenced construction in the dead of a Saturday night and completed it before sunset the next day. A newspaper article discussing these events reported that the railroad had staged a “coup d’etat” in the Goose Island neighborhood.1.10

The next day, seeing that the railroad had started construction while they were asleep, area residents took immediate action: they went to a bar. Their alderman, Peter Mahr, did his best to maintain order. He urged his constituents “to abstain from pillaging the property” of the Chicago and Pacific, but was ultimately unable to stop several enraged citizens from tearing up ties and rails, throwing them in a heap and setting them on fire. Despite their “efforts,” the rioting Goose Islanders were unable to prevent the Chicago and Pacific from completing its work before the two-year deadline elapsed.1.11

Perhaps the principal flaw in the rioters’ plan was deciding to establish their headquarters at a tavern. As the Chicago Tribune reported:

Ecocity-Publicity-Mobility

Apparently not everyone thought the Bloomingdale was cause to riot. To the contrary, its arrival “caused a rapid growth in all of the communities in the northwest section” of Chicago.1.12.1 While many citizens eventually accepted (and even embraced) the railroad’s incursion into their neighborhoods, others simply could not overlook the fact that the St. Paul’s passing trains periodically maimed and killed their families, friends and neighbors.

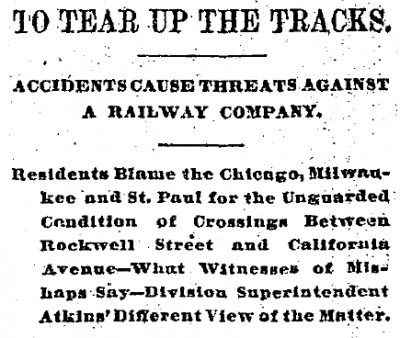

Chicago Tribune, Aug. 27, 1902, pg. 1 |

The basic problem was that the Bloomingdale Line — which still ran at grade down the center of Bloomingdale road — crossed several intersections that lacked any type of guard or safety equipment. The situation was particularly dire between Rockwell and California avenues. After two people were injured along the Bloomingdale, one area resident commented:

Left: Chicago Daily Tribune, Aug. 5, 1897, pg. 8; Right: Chicago Daily Tribune, Oct. 21, 1900, pg. 8

As the above headlines from 1897 (left) and 1900 (right) illustrate, the community’s frustration over these accidents and deaths perpetually teetered on the edge of violence. It seemed like nearly every day the paper reported another incident.1.14 Perhaps in response, the city in 1901 tried to force the St. Paul to elevate the Bloomingdale Line, but — despite the support of Mayor Carter Harrison — the effort failed.1.15

In one particularly interesting incident from July 1907, 30 “determined housewives … who were armed with umbrellas, brooms, mops, chairs, and other household weapons” tried to stop St. Paul workers from installing a switch track at Monticello Avenue that was intended to serve the Waukesha Lime & Stone Company. Although those ladies lost that particular battle, the dynamics of the war were changing: the Chicago Tribune called for the Bloomingdale to be elevated.1.16

Finally, the City Council’s patience with the St. Paul had run out. Between 1908-09, aldermen commenced something of a collateral attack on the railroad. For example, in 1908, certain aldermen questioned the legality of the St. Paul’s right of way west of Western Avenue.1.17 And the following year, one alderman offered a resolution to direct the city’s corporation counsel “to begin litigation to oust the main tracks of the [Bloomingdale Line]” west of Western Avenue.”1.18 The writing was now on the wall for the St. Paul: elevate or be kicked out of town. The pressure on the St. Paul culminated on June 27, 1910, when the City Council passed an ordinance requiring the Bloomingdale Line to be elevated.1.19

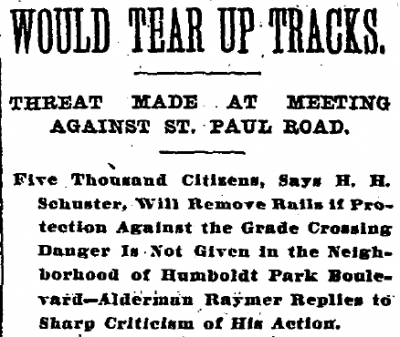

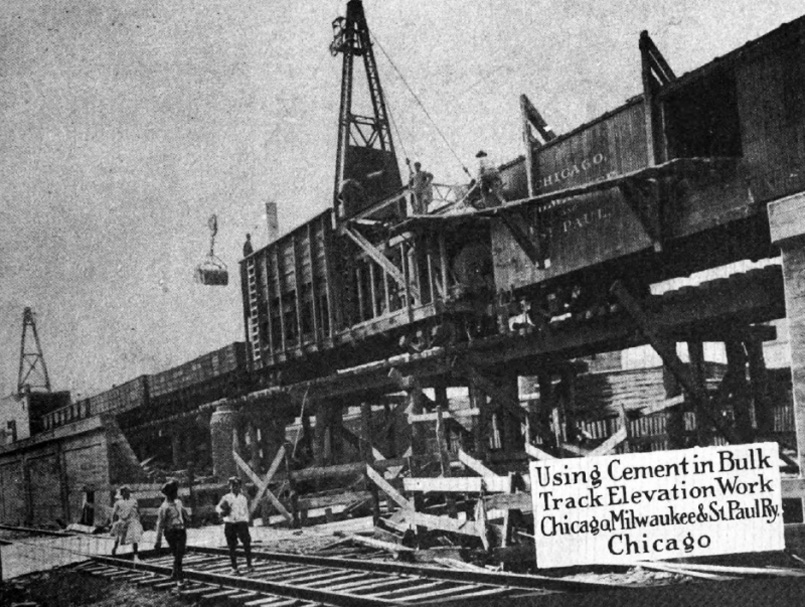

So, the city thrust upon the St. Paul the job of elevating the Bloomingdale. This was no minor task. Practically speaking, St. Paul had to find a way to elevate its double set of tracks over a distance of 2.6 miles along with “numerous side tracks and industrial connections.” Moreover, the city required the St. Paul to complete its work within five years (i.e. by 1915)1.20 and, concurrently, pave with bricks the part of Bloomingdale not used by the railroad.1.21 (These bricks can still be seen today, peeking out from thin layers of asphalt.)

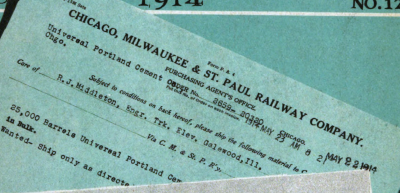

Fortuitously for the St. Paul, it employed a man equal to the challenge: Robert James Middleton, the railroad’s assistant engineer. In 1904, only one year after he graduated from the University of Arkansas with a Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering, Mr. Middleton oversaw construction of the sewer system in Fulton, Missouri. He joined the St. Paul in 1906 and worked on a track-elevation project in Evanston from 1908-1911.1.21.1 Mr. Middleton was, therefore, the natural choice to manage the Bloomingdale track-elevation project, which he did from 1913-1915 with the title “Engineer of Track Elevation.”1.22

Universal Bulletin, No. 123, Aug. 1914, pg. 144

The work that Mr. Middleton and his colleagues performed on the track-elevation project earned acclaim from engineering and construction publications of the time. The St. Paul — at one time utterly recalcitrant regarding elevating the Bloomingdale — attacked the engineering and construction aspects of the work with gusto. It employed “the most up-to-date construction methods including specially built apparatus and the use of material to the best advantage.”1.23 Particularly impressive was the St. Paul’s use of bulk cement, which resulted in greater efficiency and economy.1.24 Engineers delivered the cement where it was needed by way of a “moveable crane type of elevator” that conveyed one-half yard batches every 1.5 minutes, which industry observers deemed novel, efficient and impressive.1.25

Both images: Universal Bulletin, No. 123, Aug. 1914, cover page

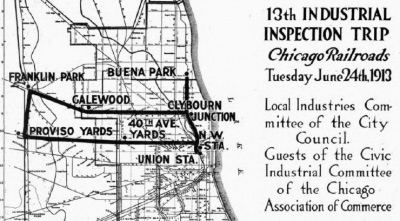

While Mr. Middleton labored to complete the elevation project on time, St. Paul executives took the opportunity to show off their engineering marvel then in progress. On June 24, 1913, a delegation of representatives of local Chicago industries embarked on an “industrial inspection trip” of Chicago railroads, including the Bloomingdale Line. G.L. Whipple, a St. Paul executive who went on the tour, touted his railroad’s elevation work and its plans to take the opportunity to create two large rail yards along the route.1.26

Both images: Chicago Commerce, June 27, 1913, pg. 13-14

On June 30, 1915, at long last, the Bloomingdale Line’s track elevation was 95 percent complete. As a result of the St. Paul’s efforts, resources and ingenuity, the project eliminated 35 grade crossings that had previously caused much suffering for the residents who lived nearby the line.1.27

Although the Bloomingdale Line caused great consternation for residents prior to its elevation, it undeniably spawned the formation of an industrial corridor surrounding it that would last for more than 100 years. During that time a great many manufacturers and industries situated themselves on either side of the Bloomingdale’s tracks. From a Forgotten Chicago perspective, the real story of the Bloomingdale Line is the story of the companies that surrounded it and depended upon it.

Certain of those companies relied on it more literally than others. Businesses that were directly next to the Bloomingdale Line used the rail line as a part of their daily business operations. They accomplished this by erecting their own rail connection with the Bloomingdale that spurred off of the main line via a switch and terminated at a point in or near the affected company.

Left: Historic Aerials; Right: Terence Banich

These “switch” tracks or “side” tracks, as they were usually called, existed at grade prior to the Bloomingdale Line’s elevation in 1913-15. Those companies that wished to maintain their interconnection with the Bloomingdale Line were obligated to elevate their switch tracks as well.2.0 This was often done by mounting the side tracks on a trestle or, if there was sufficient room, an earthen embankment. To the extent that a switch track crossed over, on or in a city thoroughfare, the business owner had to obtain the City Council’s approval by ordinance.2.1

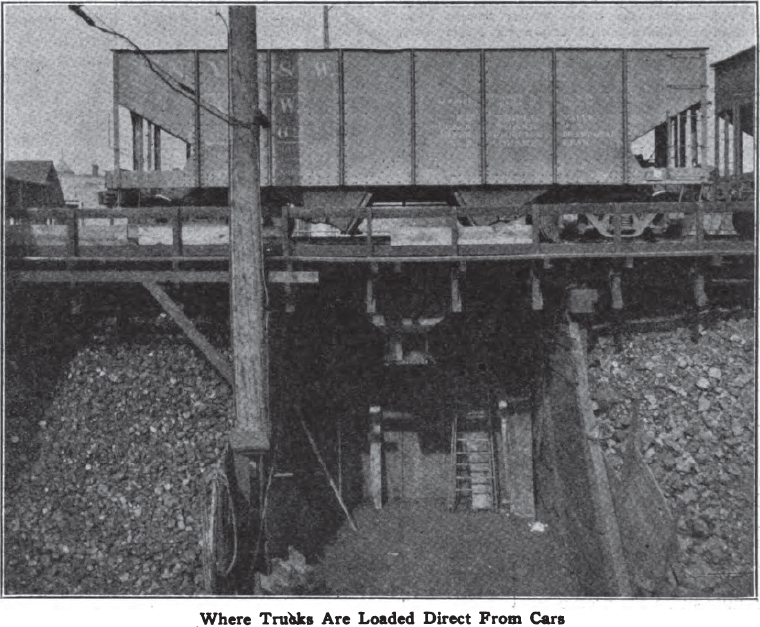

Below is a typical switch track mounted on a wooden trestle. This example, which is pictured behind the Majestic Wood Carving Company in the late 1940s, connected to the Bloomingdale Line just west of Maplewood Avenue.

Archives of the Majestic Wood Carving Company

Archives of the Majestic Wood Carving Company

Below left, the Independent Snuff Company’s switch track connection with the Bloomingdale main line, just to the east of Damen Avenue (then called Robey Street). The site is presently Churchill Field Park, so named because the Churchill Cabinet Company (discussed below) once owned it. Below right, the remnants of the point at which the Independent Snuff Company’s switch track trestle branched off of the Bloomingdale main line and crossed Robey Street.

Left: Sanborn; Right: Google Maps

In one important sense, the relationship between the Bloomingdale-area companies and the St. Paul railroad was symbiotic. As one St. Paul official put it in 1913, as the track-elevation project was underway, “[t]he local business concern located on a railroad wants to get its money out of that car, therefore the better facilities of the railroads the better return to the merchants and to the citizens.”2.2

But the railroad’s motives were not entirely altruistic; servicing the industries along the Bloomingdale Line represented a way for the St. Paul railroad to make additional money. Railroads received head-end revenue for hauling goods to or from industry along its route. Usually transported in cars nearest the locomotive, these commodities or shipments were known as head-end traffic.2.3 So, while the industries directly adjacent to the Bloomingdale Line needed it to receive goods from and place goods into interstate commerce, the St. Paul benefited from that arrangement as well.

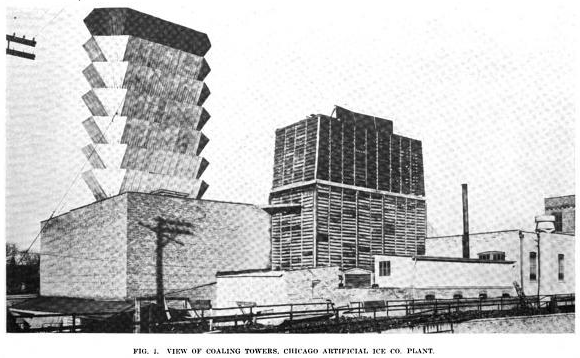

Left: Ice and Refrigeration, Vol. LVI, No. 1, pg. 63 (January 1, 1919); Right: Terence Banich

At least seven companies — six of which directly utilized the Bloomingdale Line — have interesting stories to recount here. A brief sketch of each follows.

The Delineator, July 1922, pg. 2 The Delineator, July 1922, pg. 2

|

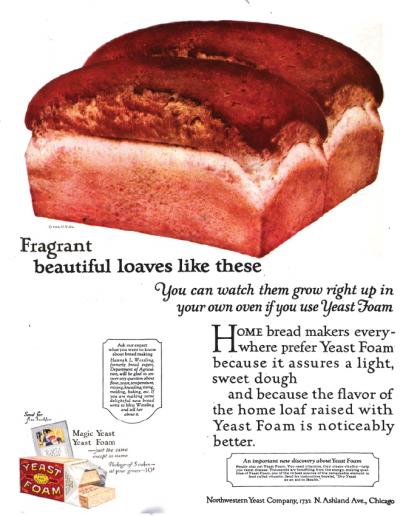

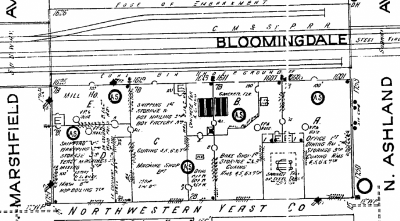

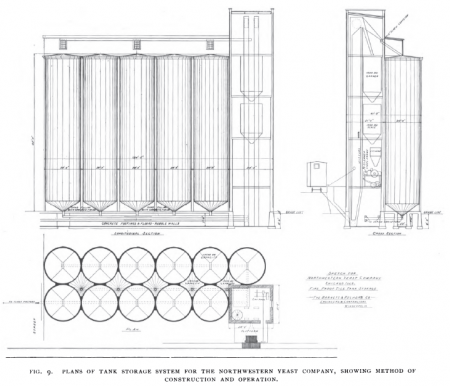

The business that became the Northwestern Yeast Company was incorporated in May 1884 as the George A. Weiss Malting and Elevator Company. Its principal business line was to bake yeast, and eventually it boasted a malting capacity of 400,000 bushels.2.4 As one journal noted, it was “thoroughly conversant with the properties and effects of yeast.”2.5 Northwestern Yeast marketed and sold a product known as Yeast Foam Tablet, touted as “pure yeast in tablet form, in a convenient pocket size bottle”2.6 that acted as a tonic to stimulate the appetite, improve digestion and correct many disorders due to malnutrition.2.7 By the late 1910s, one business journal referred to it as “a multi-million dollar corporation which practically monopolizes the dried yeast field.”2.8

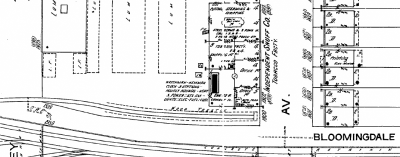

The company eventually relocated to the southwest corner of Bloomingdale and Ashland avenues. On January 3, 1894, the city granted Northwestern Yeast the privilege of operating a switch track with the Bloomingdale,2.9 which was later elevated on an embankment along with the rest of the line between 1913-1915. |

Left: Sanborn; Right: Terence Banich

The Brickbuilder, Vol. 11, No. 11, pg. 236 (Nov. 1902) The storage tanks destroyed in Northwestern Yeast’s 1912 fire.

|

On February 5, 1912, Northwestern Yeast suffered a massive fire that destroyed its entire plant, grain elevator and seven-story brick malthouse. Watched by thousands of spectators, the fire at one point threatened to destroy several blocks of buildings2.10 and caused Northwestern Yeast a loss estimated at $500,000 in 1912 dollars2.11 – over $11 million today. Significantly, the fire also destroyed the freight cars and the tracks of the Bloomingdale Line, which adjoined with Northwestern Yeast’s plant.2.12

But the company recovered from the devastating fire. In 1919, Benjamin Norton Hair, a Civil War veteran, was president of Northwestern Yeast,2.13 and one of his “partners” was an impressive fellow called Franklin H. Head, who a publication described as a “lawyer, manufacturer, banker, insurance man and magnate.”2.14 While it is not clear what ultimately became of the Northwestern Yeast Company, it seems that a company called the Garden City Plating & Manufacturing Company, a manufacturer of specialty hardware and fixtures, occupied this site by 1950.

Sadly, the property was fated to experience yet another horrific fire. The buildings at this location, which were abandoned and vacant by 1970, were destroyed by a “spectacular and deadly fire” on July 7 of that year, and a Chicago firefighter, John P. Walsh, Jr., died as a result of injuries he sustained while attempting to douse the flames. Two years later, the Chicago Park District acquired the site and transformed it into Walsh Playground Park, named in honor of the fallen firefighter,2.15 which it remains today.

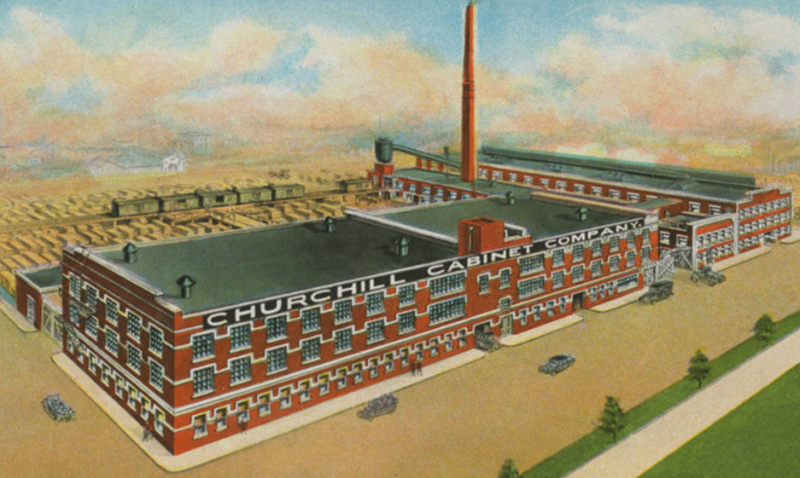

Churchill Cabinet Company was organized in 1904 by telephone industry veteran Ole Gullickson with its exclusive line of business being the production of telephone cabinets. Its facilities were located at 2119 W. Churchill Street, immediately adjacent to the Bloomingdale Line. Churchill Cabinet, which adopted the name of the street on which its facilities were situated,2.16 had early success. Within its first year of existence, a trade magazine described Churchill Cabinet’s facilities as “one of the largest establishments of its kind … fitted out with every modern appliance,” and praised its workmanship as “furnishing the very best telephone cabinets which can be produced.”2.17 The early news was not all good for Churchill Cabinet, however; in the summer of 1911, a fire destroyed its entire plant, causing a loss estimated at $50,000 ($1.15 million adjusted for inflation).2.18

State of Illinois

Churchill Cabinet had a switch track connection with the Bloomingdale Line. In fact, in a likely reference to its interconnection with the Bloomingdale Line, The Telephone Magazine touted Churchill Cabinet as “especially well prepared to handle carload shipments[.]”2.19 Below left is a 1973 aerial image in which Churchill Cabinet’s switch track is visible. The structure closest to the main line is supported by an earthen embankment and then transitions to a trestle. Below right is a remnant of the embankment that once supported the first half of Churchill Cabinet’s switch track.

Left: Historic Aerials; Right: Terence Banich

|

In the early 1970s, after changing owners, Churchill Cabinet diversified and began building cabinetry for the coin-op industry (i.e., pinball and arcade games).2.20 Again, Churchill Cabinet found success right out of the gate: it became one of the best-known pinball enclosure manufacturers in the world.2.21 By August 2000, however, Churchill Cabinet was forced to sell its Churchill Street facility and liquidate its capital equipment located there.2.22 The property was later converted for residential use, though the developers retained Churchill Cabinet’s painted signage. Despite the closure of its Chicago facility, Churchill Cabinet relocated to Cicero and remains in the pinball business today. |

Terence Banich The former Churchill Cabinet Company as it appears today as a residential building.

|

Factory & Industrial Management, Vol. 61, Issue 5, pg. 14 (Mar. 1, 1921) |

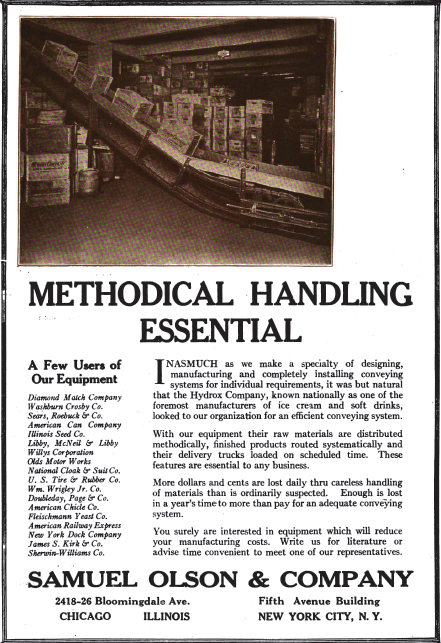

Originally known as Samuel Olson & Co., this enterprising firm located at 2418 W. Bloomingdale Avenue manufactured and sold “conveying” machines that essentially moved objects in an industrial or commercial setting from one place to another by conveyor belts, elevation or pneumatic tubes.2.23 For example, Olson sold a machine it dubbed the “Subveyor,” which was a system for use in hotels and restaurants to convey soiled dishes to the “dishwashing department” and to return clean dishes to the floor above. In fact, in 1941, the United States Patent & Trademark Office awarded Olson a patent (no. 2,257,512) for its invention of an “automatic loading and delivery mechanism for conveyors.”2.24

Although Samuel Olson Manufacturing was directly alongside the Bloomingdale Line, it does not appear to have connected with the line via its own side track. Many other switch tracks were in the immediate vicinity, however; perhaps Olson simply used one of them. It is also possible that Mr. Olson was a customer of vehicular shipping. While the company was still operating by 1961 – albeit as a division of Cherry-Burrell Corporation2.25 – its ultimate fate is not known. Mr. Olson’s former factory remains extant today and is in use as an art gallery. |

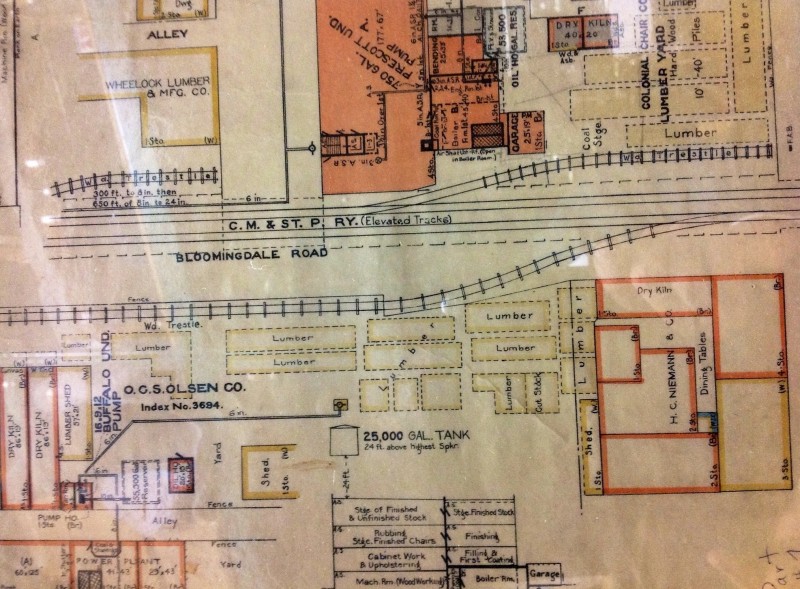

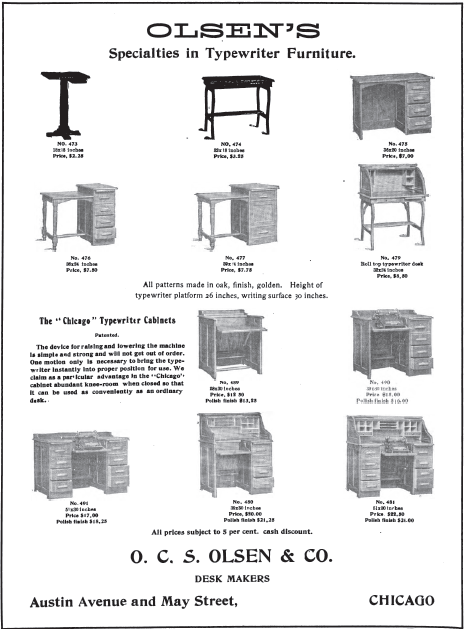

| Founded in 1890 by Olaf C.S. Olsen, a Norwegian immigrant, the O.C.S. Olsen Company manufactured office desks for many years in a large facility at 2511 W. Moffat Street that was formerly occupied by the World’s Fair award-winning L.M. Hamline & Co. and another concern known as Sprague, Smith & Co.2.26 Mr. Olsen acquired the Moffat Street facility in 1907 to obtain more floor space than his prior location on Austin Avenue had. After an expansion, the factory could boast dedicated floors for machinery and offices, as well as the use of dry kilns that could handle a capacity of 60,000 feet of lumber.2.27

By 1912, Mr. Olsen could be described as a “wealthy desk manufacturer” and, as he unfortunately discovered, a blackmail target. In July 1912, two less-than-master criminals – referring to themselves as “Black Hand” – delivered a letter to Mr. Olsen stating: “Leave $10,000 in a brown package near the south end of the St. Paul railroad tracks at Bloomingdale road and Rockwell street at 8:30 tonight. Your failure to do so will cost your life.” Subsequent letters threatened to “blow up” the O.C.S. Olsen factory building if their demands were not met. As a result of some cunning strategy devised by detectives of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, the two miscreants (one of whom was a disgruntled former O.C.S. Olsen employee) were apprehended near the Bloomingdale tracks.2.28 |

American Cabinet Maker & Upholsterer, Vol. 71, No. 13, pg. 23 (Jan. 7, 1905) American Cabinet Maker & Upholsterer, Vol. 71, No. 13, pg. 23 (Jan. 7, 1905)

An advertisement for Mr. Olsen’s line of typewriter desks which ran two years before his company’s move to Moffat Street.

|

Terence Banich

The O.C.S. Olsen factory was directly adjacent to the Bloomingdale Line and maintained a switch track connection with it.2.29 In fact, when Mr. Olsen began operating out of the Moffat Street building in 1907, one industry magazine commented: “The Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul tracks run just south of the factory, with side tracks right into the lumber yards and shipping rooms, a convenience possessed by few furniture factories in Chicago.”2.30 Thus, from the outset, the Bloomingdale Line was an integral part of the O.C.S. Olsen Company’s operations.

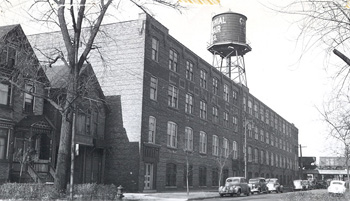

Below is a circa 1920s view of the O.C.S. Olsen Company’s very large switch-track trestle at the corner of Maplewood and Bloomingdale avenues. The Colonial Chair Company looms in the background. Its switch-track trestle is also visible on the right side of the photograph. Both companies evidently received shipments of lumber via the Bloomingdale.

Archives of the Majestic Wood Carving Company