Chicago is, as one writer put it, a “city of travelers.”1 The city’s sheer sprawl made that moniker inevitable. It also led to the creation of a transportation system that, at its apogee, consisted of a web of streetcars, diesel buses, electrified trolleybuses and elevated railways and subways. But not every mode of public transportation that once served Chicago is extant today. Streetcars, for example, last operated in Chicago in June 1958, and trolleybuses retracted their trolley-wire poles for the last time in March 1973. As those modes of transportation disappeared, the infrastructure that supported it was eventually demolished as well.

Serhii Chrucky

The “L,” by contrast, is obviously still alive and well in Chicago. But that does not mean all parts of the “L” that once existed still exist today. After the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) assumed operational control of the “L” in 1947, it abandoned and ultimately demolished seven entire lines and branches. Although CTA largely eliminated even the slightest trace of these structures in the 1950s and 1960s, some remnants still exist today. This article documents some of the known physical remains of that long-gone rail infrastructure.

First, however, a brief history of rail transit in Chicago is necessary to place the specific remnants in context and to understand CTA’s justification for dismantling any part of the rail system.2

Public transportation, as we now conceive of it, began in Chicago in 1859, 26 years after the State of Illinois incorporated it as a city.3 At that time, contractors drove the first spike for Chicago’s first streetcar line at State and Randolph streets.4 The genesis of what would become the CTA bus and rail infrastructure had, by April 1859, gotten off to a humble start: one horse-drawn streetcar traveling upon a single track on State Street from Randolph Street to the Southern Hotel on 12th Street.5

Chicagoans had to wait another 33 years for rail service to get off the ground – literally. Chicago’s first actual rail line, the privately-owned Chicago and South Side Rapid Transit Railroad Company, incorporated in 1888.6 On May 28, 1892, the first “L” train – which consisted of six wooden olive green and yellow coaches operated by steam locomotion – took its inaugural trip down the elevated “Alley L” from Congress Street to 39th Street.7 The public’s objections to the unsightliness of elevated train lines were quieted by the fact that the 34-block trip took the “L” only 9.5 minutes to complete.8 As one transit writer quipped, “For the first time, the words ‘rapid transit’ took on new meaning.”9

Called the “Alley L” because its route was completely through city-owned alleys,10 the South Side Rapid Transit line was Chicago’s first experience with bona fide intracity rail service. It would, of course, not be the last. In the years that followed, several competing, privately-owned rail lines began service in different areas of Chicago: the Lake Street Elevated Railroad Company (1893);11 the Metropolitan West Side Elevated Railroad Company (1895);12 the Union Elevated Railroad Company (1895);13 and the Northwestern Elevated Railroad Company (1899).14 These purely private concerns built much of the infrastructure for the CTA rail lines we now know as the Red, Blue, Green, Brown and Pink Lines. By 1909, after each of these companies had significantly expanded their operations, they were jointly capable of serving large swaths of the city’s neighborhoods and as well as its then-outlying and undeveloped “prairie” areas.

But at that point the original elevated rail companies were not operating jointly. There were at least five attempts to unify the rapid transit lines under common ownership, all of which eventually proved unsuccessful.15 Although the companies merged in 1924 as a single entity, the Chicago Rapid Transit Company (CRT),16 persistent financial distress caused CRT to spend much of the early 20th century in bankruptcy or receivership, with its operations managed by fiduciaries appointed by the United States District Court.17 Somewhat paradoxically, CRT continued to expand its service and operations. CRT eventually could boast 227.49 miles of track that carried an average of 627,157 passengers per weekday on 5,306 scheduled trains to and from 227 stations in the Chicago metropolitan area.18

By the end of World War II, however, it became clear that private ownership of the rapid transit lines was hopelessly unprofitable. CRT simply could not generate sufficient revenue from fares to handle the costs of operation, plant renewal, modernization and expansion needed to match the public service demands caused by the growth of the city and its suburbs.19 Unification under a single municipal – as opposed to private – corporation was the only logical alternative. In April 1945, the Illinois General Assembly created the CTA to accomplish that goal,20 and by October 1947, CTA had purchased all of CRT’s assets and began to operate the “L.”21

When CTA took over, it began to examine major changes that CRT apparently never considered, including conversion of low-traffic routes to more economical technologies and adapting the rail system to changing land use and ridership.22 CRT never abandoned a single line and likely never closed a station.23 Indeed, as Chicago transit historian Graham Garfield characterized it, the “L” in 1947 “was a tangled series of complex schedules involving multiple express and local services, often running over the same tracks and getting in each others’ way.”24 To make its task even more challenging, CTA assumed control over public transportation during the ascendancy of the automobile and the superhighway as well as the flight of city dwellers to the suburbs.25 These factors caused the existing rapid transit lines to lose ridership.26 To address these changes, in addition to closing scores of stations, CTA abandoned seven lines and branches:

| Line/Branch | Built by | Abandoned/Demolished |

| Westchester Branch | CRT | 1951/various |

| Logan Square Branch (between Lake & Evergreen) | Metropolitan West Side | 1951/1964 |

| Humboldt Park Branch | Metropolitan West Side | 1952/1954, 1961 |

| Normal Park Branch | South Side Rapid Transit | 1954 |

| Kenwood Branch | Union Stock Yards and Transit Company | 1957 |

| Stock Yards Branch | Union Stock Yards and Transit Company | 1957 |

| Garfield Park Line | Metropolitan West Side | 1958 |

In what might now be considered a short-sighted decision, CTA did not just discontinue services on those lines and branches; it had their supporting physical infrastructure completely demolished. Just how completely CTA removed that infrastructure is the focus of this article. But owing to the apparent thoroughness of the contractors CTA engaged to dismantle these lines or the development of the former rights of way for other uses, there are few remnants of those structures.

Logan Square Branch (Metropolitan West Side Elevated)

The elevated section of the Blue Line from Wolcott Avenue to Linden Place is all that physically remains of the Logan Square Branch of the Metropolitan West Side Elevated. The Logan Square Branch was originally a much larger and entirely elevated structure; until February 1951, there was no subway starting at Division Street as there is today.

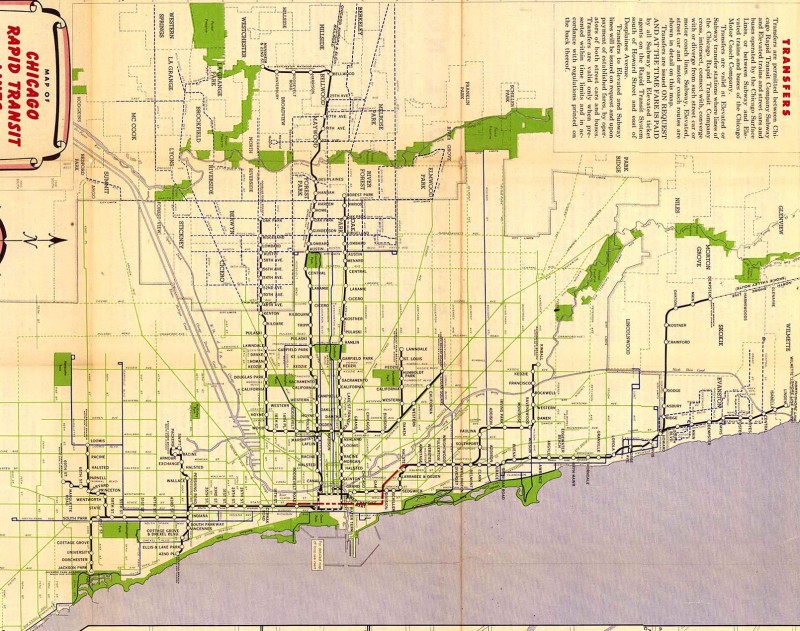

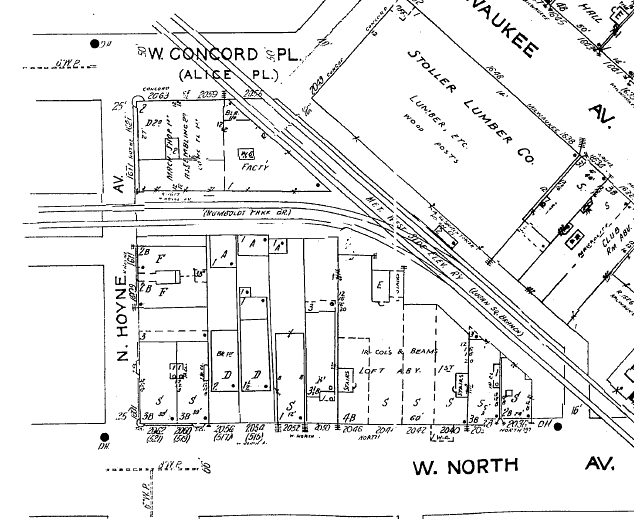

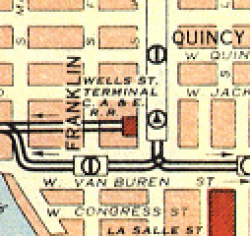

As the CRT map from 1946 (left) illustrates, the Logan Square Branch commenced at the Marshfield Junction (Marshfield Avenue, between Van Buren and Congress streets; demolished), proceeded via an elevated rail structure north along a right-of-way just to the west of Paulina Street, and then turned to the northwest just south of Milwaukee Avenue at Moorman Street, where it traveled parallel to Milwaukee and terminated at the Logan Square station (2525 N. Kedzie Avenue; demolished).

The 1946 map also demonstrates that the original alignment of the Logan Square Branch did not exactly take the most direct route into the Loop. Instead of continuing to head southeast after Damen station (as it does today), a rider had to turn due south at Paulina Street, disembark at the “Lake Street Transfer” station and then transfer to an eastbound train on the Lake Street Elevated. The Milwaukee-Dearborn Subway, which CTA placed in revenue service on February 25, 1951, eliminated the turn to the south at Paulina Street and permitted Logan Square passengers to connect directly to the Loop Elevated, without the need first to transfer to the Lake Street Elevated. CTA’s 1957 system map (above right) illustrates the routing change. At the time, CTA officials boasted the more direct routing would almost halve the travel time from the Logan Square terminal to the Loop (from 28 minutes to 15 minutes).27

Although completed in the CTA era, the Milwaukee-Dearborn Subway was planned and designed in the late 1930s and early to mid-1940s, during CRT’s stewardship of the rail system. CRT originally intended to route some trains through the new subway and others along the old Paulina elevated. When CTA took over and began a system-wide process of route simplification in the late 1940s, CTA anticipated that all Logan Square trains would proceed through the subway, while all Humboldt Park trains would take the Paulina elevated. By the time the subway was actually ready for revenue service in early 1951, however, CTA had changed course and decided that Humboldt Park trains would travel no further than Damen (more on that below), and that the Paulina elevated would be taken out of revenue service altogether.28

Left: Historic Aerials; Right: G. Krambles, Krambles-Peterson Archive.

Left: Historic Aerials; Right: G. Krambles, Krambles-Peterson Archive.

Notwithstanding which routing plan was implemented, there had to be a physical connection between the Milwaukee-Dearborn Subway and the old Paulina elevated. Though planned many years earlier, in 1950, CTA completed constructing a rail junction — called the Evergreen Junction, as it was just to the east of Evergreen Avenue — to permit trains to be routed either into the Milwaukee-Dearborn Subway or via the Paulina elevated.29 To accommodate this alternative routing, an additional inbound and outbound set of elevated tracks had to be constructed. These tracks emerged at Evergreen Junction on either side of the two preexisting, center tracks. The two outer tracks were erected on either side of what would become the subway portal (beginning at Wolcott Avenue), proceeded above the two center tracks, which descended into the subway, and near Moorman Street joined up with the old elevated structure. What is truly interesting is that the Evergreen Junction and accompanying trackage were designed and built as permanent pieces of infrastructure, but by the time they were completed, CTA had already dropped all plans to continue using the Paulina elevated in revenue service.30

Left: Historic Aerials; Right: Google Maps

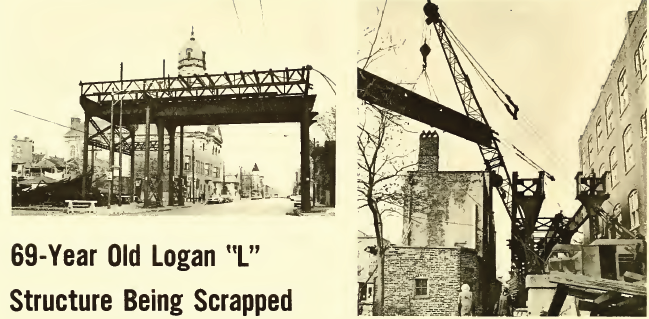

This dual alignment was not to last. In February 1964, the Chicago Plan Commission — as part of its “Washington-Hermitage Urban Renewal Project” — approved a plan to raze the disused elevated structure between Lake Street and the Evergreen Junction.31 On September 3, 1964, the Chicago Transit Board engaged the Calumet Iron & Supply Company of East Chicago, Indiana, to wreck the structure in exchange for a payment of $22,620 and the right to retain all scrap materials.32 Actual demolition work was underway by December 1964.33 CTA decommissioned the Evergreen Junction at the same time.34

The Internet Archive

The Internet Archive

There are several remnants of the now-demolished elevated alignment of the Logan Square Branch. The survey below begins at the site of the former Evergreen Junction, proceeds southeast and south toward Lake Street and ends at the site of the former Washington Junction.

Serhii Chrucky

Serhii Chrucky

Left: Street-level view of Evergreen Junction. The widened structural support for the additional southern outer track is evident here. Right: The foreground of this picture features one of many square concrete pads on the south side of the elevated structure/subway portal between Wolcott and Hermitage avenues. Each of these pads was the foundation for a vertical girder of the now-demolished elevated structure that was erected on either side of the new subway between 1946 and 1950. Note that each concrete foundation pad is directly opposite a severed girder.

Serhii Chrucky

Serhii Chrucky

Serhii Chrucky

Serhii Chrucky

Left: Sanborn; Right: Google Maps.

Left: Sanborn; Right: Google Maps.

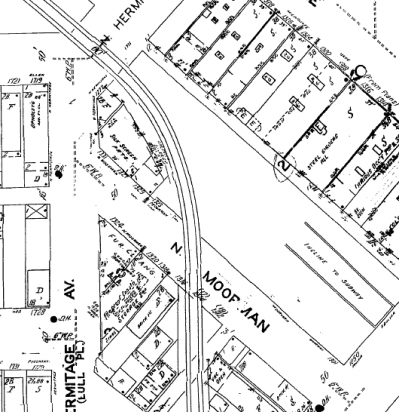

Moorman Street then and now. Left: Sanborn fire insurance map circa 1950 showing how the elevated section of the Logan Square Branch curved to the southeast, away from the subway portal. Right: A modern overhead view of roughly the same location. The oddly shaped buildings and large setbacks in this area, particularly along the 1200 block of North Paulina, evidence the elevated structure’s former right-of-way.

H.M. Stange, Krambles-Peterson Archive

H.M. Stange, Krambles-Peterson Archive

Left: The old Paulina elevated, looking north on February 24, 1951, along the 1200 block of North Paulina Street. This view features the rail infrastructure that today is evidenced by large setbacks and the angle in the residential building discussed above, shown here with an advertisement for National Security Bank. (For a larger view, click here.) Right: This February 24, 1951 picture shows the subway portal and the Paulina elevated at a point between Wood Street and Hermitage Avenue. This view places in context some the remnants discussed here, such as the concrete bases present in the alley and the severed vertical support girders extant in the subway portal’s wall. CTA would take the Paulina elevated out of revenue service the following day. (For a larger view, click here.)

Left: Terence Banich; Center: Historic Aerials; Right: Google Maps

There are precious few remnants of the demolished permanent elevated structure south of Moorman Street. Left: This is a rare example indeed: an entire vacant lot of concrete bases for the elevated structure that formerly passed overhead at approximately 1714 W. Ohio Street. Middle: An overhead view of 1714 W. Ohio Street in 1962 showing the elevated structure. Right: Roughly the same perspective today. The concrete bases appear as white dots from this elevation.

Serhii Chrucky

Serhii Chrucky

Left: Further south, there is a severed support girder embedded in concrete in an alley to the north of about 1715 W. Chicago Ave. The squat, yellow former CRT building (discussed below) is visible in the distance. Note that the severed girder is directly aligned with the old CRT building, evidencing the elevated structure’s former right-of-way. Right: Detail of severed girder in alley to the north of 1715 W. Chicago Ave.

Serhii Chrucky

Serhii Chrucky

Left: Historic Aerials; Center: Google Maps; Right: Serhii Chrucky

Continuing to the south, the elevated structure crossed over the Chicago & Northwestern and Milwaukee Road railway right-of-way at Kinzie Street. This was accomplished by way of a large steel bridge — sometimes called the “Met” bridge — that remains extant today, and is likely the largest “‘L’ remnant.” Although essentially abandoned in place in that it no longer serves as a bridge, today it acts as a signal tower for rail lines that continue to operate below. Left: Overhead view of the bridge in service in 1962. The elevated tracks are clearly visible at the top and bottom of the picture. Middle: Roughly the same overhead view today. Right: Street-level view of the bridge.

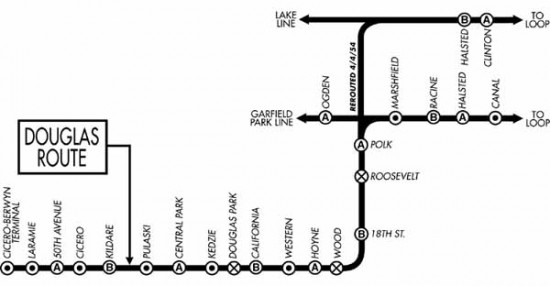

The final stop on our survey brings us to the site of the former Washington Junction. CTA activated the Washington Junction in April 1954 to allow Douglas Line (i.e., Pink Line) trains access to the Loop while CTA completed construction of what would become the Congress Line (i.e., Blue Line) in the middle of the Eisenhower Expressway.34 Why do we address this remnant in the Logan Square Branch section? Because CTA used part of the former Logan Square Branch to make this rerouting happen. As the route map (left) illustrates, Douglas Line trains originally accessed the Loop via the Metropolitan Main Line & Garfield Park branch at Marshfield Junction. During the Congress Line construction, CTA’s plan was to reroute Douglas Line trains onto the disused section of the Logan Square Branch near Washington Street and then transfer to the Lake Street Line and then into the Loop. Unfortunately, however, the old Logan Square Branch originally passed over the Lake Street elevated (at the Lake Street Transfer station) but did not have a junction with it. Consequently, CTA had to build a new span of elevated structure to make that direct connection. This was the the raison d’être of the Washington Junction: a newly-built elevated track branched off of the old Logan Square Branch at Washington Junction and turned to the east to link with the Lake Street Line. Effective April 4, 1954, Douglas Line trains were routed into the Loop via this new alignment. After the Congress Line opened on June 22, 1958, however, it was no longer needed, as Douglas Lines used the new Congress Line to reach the Loop via the Milwaukee-Dearborn Subway.35

Left: J.J. Buckley; Right: B.L. Stone; both from the Krambles-Peterson Archive.

Left: J.J. Buckley; Right: B.L. Stone; both from the Krambles-Peterson Archive.

Left: This photo taken on June 24, 1961 illustrates some of the infrastructure discussed above, including the then-disused Logan Square elevated tracks passing over the abandoned Lake Street Transfer station (left), and the tracks added in 1954 to make the connection to the Lake Street Line (right). The Washington Junction was behind and to the left of the photographer. (For a larger view, click here.) Right: In this image from 1950, a single-car Westinghouse train is shown traveling southbound at Fulton and Paulina streets about to traverse the old Met “L” bridge over the Milwaukee Road/Northwestern tracks. (For a larger view, click here.)

Left: Historic Aerials; Center: Google Maps

Left: Overhead view of Washington Junction in 1962. Note that there are two parallel spans of elevated trackage. The left set of tracks is part of the former Logan Square Branch, while the right set is the alignment CTA added in 1954 to connect the Douglas Line to the Lake Line. Center: Modern overheard view of the former Washington Junction. The structure’s curve belays the one-time existence of the Logan Square tracks which, as discussed above, were demolished beginning in 1964.

Click here to view a detail of the remnants of Washington Junction in April 2003. This obvious missing sections of the box girder elevated structure and half-used stone bases evidence the point where the old Logan Square Branch once connected and continued northward to Milwaukee Avenue.36 This area was entirely rebuilt circa 2005 as part of the Pink Line realignment. Interestingly, Pink Line trains now access downtown using the same service pattern Douglas Line trains used between 1954-58.37

Humboldt Park Branch (Metropolitan West Side Elevated)

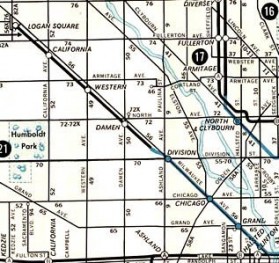

A modern-day resident of Chicago’s West Town neighborhood might be quite surprised to learn that an elevated rail line once linked Wicker Park and the north side of Humboldt Park. The Humboldt Park Branch, as it was known, did just that from 1895 to 1954. As a CRT route map from 1938 (left) illustrates, the Humboldt Park Branch emerged from the Logan Square Branch just to the northwest of Damen station and proceeded due west parallel to North Avenue. Its right-of-way was about 200 feet north of North Avenue, immediately adjacent to the alley. The branch consisted of only six stations, commencing at Western Avenue and terminating at Lawndale Avenue (although CRT intended to extend the branch further west when ridership justified it). Because the Humboldt Park Branch historically had only modest ridership levels, its days were numbered when CTA took over the “L”‘s operations in 1947.38

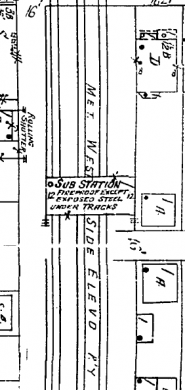

Sanborn

After identifying the stations and lines that were most uneconomical and had the lowest ridership, CTA had decided in early 1951 to abandon the line entirely coincident with the opening of the Milwaukee-Dearborn Subway in February 1951. CTA’s plans for outright abandonment were derailed, however, when affected residents and their alderman objected.

North and Pulaski Historical Society

CTA compromised by demoting the Humboldt Park Branch to a mere shuttle between Lawndale and Damen. This meant its trips into the Loop were over: Humboldt Park passengers now had to disembark at Damen Junction (as the Logan-Humboldt rail junction was called), walk along a catwalk to Damen station and transfer to the Logan Square Branch.39 But the branch’s stay of execution was short lived.

On April 15, 1952, the CTA Board voted to abolish the Humboldt Park Branch, explaining that traffic on the branch was simply insufficient to warrant its continued operation. Specifically, CTA officials noted that (a) traffic on the Humboldt Park Branch had declined from 12,550 passengers per day in 1910 to a mere 1,250 passengers per day in 1951, and (b) the Humboldt Park Branch paralleled and duplicated CTA’s trolleybus service on North Avenue — a mere 200 feet to the south of the elevated tracks.40 In its place, CTA planned to institute additional trolleybus service along North Avenue.41 Although disappointed residents and their alderman sued to stop the line’s closure,42 the Humboldt Park Branch closed forever on May 4, 1952.43 CTA then moved quickly to demolish the Humboldt Park’s elevated tracks: two short years later, the tracks between Lawndale and Western avenues were removed (above right). The final half-mile stub of the Humboldt Park Branch’s elevated structure between Western and Damen Junction was not removed until July 1961.44

J.R. Williams, Krambles-Peterson Archive.

J.R. Williams, Krambles-Peterson Archive.

From this now-demolished tower, CRT and CTA employees would monitor activity at the Damen Junction. This photograph was likely taken in 1952, during the Humboldt Park Branch’s final days. The astute observer can still see the painted wall ad beginning with “North …” as Blue Line trains arrive at and depart from the Damen station.

Terence Banich

Terence Banich

Very few remnants of the Humboldt Park Branch remain. Perhaps its most prevalent remnant is the vacated right-of-way between Damen and Lawndale avenues. Although much of that land has been developed or dedicated to other uses, several sections of the branch’s former right-of-way appear oddly vacant and, as such, are ghostly reminders of the structure’s one-time presence, such as this example at Fairfield Avenue (left).

Right: The staggered angles of this old commercial building evidence the Humboldt Park Branch’s right-of-way, as the extra space they created provided the clearance necessary for the elevated structure to curve away from the Logan Square Branch and proceed west.

Serhii Chrucky

Terence Banich

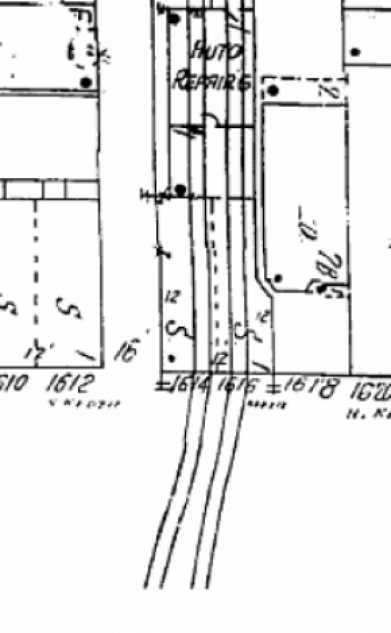

About a mile and a half west of Damen Junction was the Humboldt Park Branch’s Kedzie station. Although no trace of the station itself remains, a former CRT building remains extant across the street. This structure (right) is — like the building at 1715-17 W. Chicago Avenue — of “squat” design because it was situated under the elevated structure. CRT likely situated this building directly across the street from the Kedzie station for commercial purposes to supplement its revenue.45

Left: This image from a Sanborn fire insurance map circa 1950 illustrates how the Humboldt Park Branch passed above the former CRT building located at about 1614 N. Kedzie Avenue. Center: Detail of the former CRT building’s southern exterior wall. Note that a vertical steel girder — that once supported the elevated structure that passed overhead — remains embedded in the masonry.

Left: Terence Banich; Right: Sanborn

Two stops west of Kedzie station was the Humboldt Park Branch’s terminal at Lawndale Avenue. Left: Although nothing of the terminal itself remains (a car wash occupies the site), the branch’s electrical substation remains extant about 150 feet to the east, in the path of the branch’s former right-of-way. Right: This image from the Sanborn fire insurance map circa 1950 situates the Lawndale Substation under the elevated tracks.

Wells Street Terminal (Metropolitan West Side Elevated)

Chicago-L.org |

Part of the Met’s original transit plan was to have a terminal on Wells Street, just south of Jackson Boulevard (left).46 Completed in 1904, the Met’s Fifth Street Terminal (as Wells Street was then called) featured four tracks behind a facade that faced Fifth Avenue, as well as certain concessions.47 In 1926, CRT expanded and improved Wells Street Terminal to include, among other things, two additional levels and a new substation under the tracks at Franklin Street.48 After CTA took over the “L” in 1947, it eventually revised the entire way in which the rail system operated such that stub terminals, like Wells Street Terminal, were obsolete.49 Wells Street Terminal was demolished in 1955.50 |

W.C. Janssen, Krambles-Peterson Archive.

The Wells Street Terminal in September 1953. The rear of the terminal’s façade is in the distance. The extant substation, shown below, was beneath the elevated structure, closer to the terminal itself.

Serhii Chrucky

Serhii Chrucky

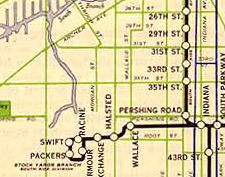

Stock Yards Branch (Union Stock Yards and Transit Company)

As its name implies, the Stock Yards Branch was built for a single purpose: to provide passenger rail service within the sprawling, 320-acre Union Stock Yards, Chicago’s meat-packing district. As illustrated on CRT’s 1946 map (left), the Stock Yards Branch was a seven-station stub that connected with the other parts of the South Side Elevated (i.e., today’s Green Line) at Indiana. From Indiana, the branch proceeded westward toward the Stock Yards, which it reached at approximately 4100 south. The track then made a loop in the “Packingtown” part of the yards and headed back toward Indiana station.52 After a few devastating fires and the decline of the Stock Yards themselves, CTA discontinued all service on the Stock Yards Branch on October 6, 1957.53 The steel elevated structure itself was dismantled sometime thereafter.

Left: Historic Aerials; Right: Google Maps

Although severed girders were once visible in area sidewalks, almost no remnants of the Stock Yards Branch exist today. However, at least one structure evidences the branch’s former right-of-way at the site of where its Halsted station once stood. Left: Aerial view of the Stock Yards Branch’s Halsted station, circa 1952. Right: A modern-day aerial view of the same location. The Stock Yard Branch’s right-of-way is evident in the angle of the building that was once to its north.

Left: Google Maps; Right: G. Krambles, Krambles-Peterson Archive.

Left: Google Maps; Right: G. Krambles, Krambles-Peterson Archive.

Left: Detail of former site of the Stock Yards Branch’s Halsted station. The building angle referred to above is evident on the right. Right: The Halsted station of the Stock Yards Branch on July 9, 1952, looking north. The extant building discussed in the left image can be seen here on the north side of the station. Incidentally, the brown and orange 4000-series train shown here was specially assigned to the Democratic National Convention, which was happening in Chicago at the time. (For a larger view, click here.)

Lake Street Line (Lake Street Elevated Railway Company)

The part of today’s Green Line that proceeds above Lake Street is one of the oldest sections of the entire network: it was placed into service in 1893 by the Lake Street Elevated Railway Company.54 By 1947, when CTA assumed control over Chicago’s rail system, it derided the Lake Street Line’s mix of local and express services as a “conglomeration moving at a slow speed.”55 The CRT map from 1938 (left) illustrates the Lake Street Line about nine years before the CTA takeover; many stations are shown that are not part of today’s Green Line. This is because in April 1948 CTA implemented its first major service revision to the rail system on the Lake Street Line, which included a swath of station closures. In an effort to lessen travel times and simplify operations, CTA introduced A/B “skip-stop” service, closed ten of the line’s stations (including its downtown terminal, the Market Stub Terminal), and rerouted all trains onto the Loop.56

Homan station, however, survived the station closures of 1948. Homan — which was originally called “Garfield Park” — was similar to the other stations that Lake Street Elevated Railway Company built in the early 1890s.57 Designed in the Queen Anne style that was popular in the United States from 1880 to 1910,58 but enhanced with a touch of Gothic Revival, Homan station would have fit perfectly within a cityscape of architecturally similar structures, such as the “tied houses” that Schlitz was building all around Chicago around the same time. Homan station featured two station houses, which showcased the Queen Anne/Gothic Revival styling, as well as boarding platforms on either side for inbound and outbound trains.59 The structural support for the station houses came from four vertical girders with bases embedded in the sidewalk, near the edge of the curb.

In 1994, CTA closed the entire Green Line for renovation, along with Homan station. When the Green Line reopened in 1996, however, Homan remained closed. Because CTA felt that Homan was too close to Kedzie station, it wanted to demolish Homan and open a new station two blocks to the west. In 2000, after consulting with the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency and many years of planning and debate, CTA carefully took apart Homan station and ultimately reconstructed it at Lake Street and Central Park Avenue, adjacent to the Garfield Park Conservatory.60 Thus, from an architectural perspective, what was Homan (or Garfield Park) station for 101 years was reborn in June 2001 as the Conservatory-Central Park Drive station.61

Left: Olga Stefanos; Right: Google Maps

Left: Olga Stefanos; Right: Google Maps

Homan station then and now. Left: Homan station in 1985, looking north. In addition to the architectural elements discussed above, two of the four girders that provided vertical support for the station house are shown here, just at the edge of either curb. Right: A modern view of where Homan station once stood, looking south. All that remains of the architectural splendor that once graced this intersection are the two columns that supported the north station house.

After assuming control of the “L”‘s operations in 1947, CTA closed nearly 100 stations that were uneconomical and had the lowest ridership.62 Although the vast majority of these stations were eventually demolished, there are some disused or abandoned “L” stations around Chicago. These include:

| Station | Line/Branch | Abandoned |

| Ellis-Lake Park | South Side Rapid Transit, Kenwood Branch (Green Line) | 1957 |

| South Parkway | South Side Rapid Transit, Kenwood Branch (Green Line) | 1957 |

| Vincennes | South Side Rapid Transit, Kenwood Branch (Green Line) | 1957 |

| California Avenue & Eisenhower Expressway | West-Northwest Route (Blue Line) | 1973 |

| Kostner Avenue & Eisenhower Expressway | West-Northwest Route (Blue Line) | 1973 |

| Central Avenue & Eisenhower Expressway | West-Northwest Route (Blue Line) | 1973 |

| Wentworth | South Side Rapid Transit, Englewood Branch (Green Line) | 1992 |

| Racine Avenue & 63rd Street | South Side Rapid Transit (Green Line) | 1994 |

| 58th Street & Prairie Avenue | South Side Rapid Transit (Green Line) | 1994 |

| Randolph/Wells | Union Elevated Railroad Company (Loop) | 1995 |

While obviously “remnants” within the scope of this feature, these former stations are already very well documented on Graham Garfield’s website: Chicago-L.org. Accordingly, we do not address them here, and instead invite you to follow the links to that website in the above table.

1. Williams, Michael, Richard Cahan, and Bruce Moffat. Chicago: City on the Move. Chicago: Cityfiles, 2007. 14. Print.

2. We include this brief historical overview of the history of rail transit in Chicago only to provide context for the remnants discussed herein. For a much more comprehensive examination of that subject, we recommend you visit Graham Garfield’s website, Chicago-L.org.

3. Krambles, George and Art Peterson. CTA at 45: A History of the First 45 Years of the Chicago Transit Authority. Oak Park: George Krambles Transit Scholarship Fund, 1993. 1. Print. Act of March 4, 1837, 1837 Ill. Laws 50; United States v. City of Chicago, 48 U.S. (7 How.) 185, 186 (1849).

4. Williams 16.

5. Ibid.

6. Garfield, Graham. “Chicago ‘L’.org: History – The Original ‘L’ Lines.” Chicago ”L”.org. Web. 16 Oct. 2010.

7. Williams 50; Krambles 21.

8. Williams 50.

9. Ibid.

10. Garfield, “The Original ‘L’ Lines”; Krambles 21.

11. Krambles 24.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Krambles 7.

16. Garfield, Graham. “Chicago ‘L’.org: History – Unification.” Chicago ”L”.org. Web. 16 Oct. 2010.

17. Krambles 7. This remained so right up to the end of private ownership of CRT as well as Chicago Surface Lines, which operated the city’s streetcars. From about 1938 until the day CTA took over in 1947, both CRT and CSL were debtors in bankruptcy, with their operations subject to the superintendence of United States District Judge Michael L. Igoe. “City’s Traction Lines Merged for New Epoch.” Chicago Daily Tribune [Chicago] 1 Oct. 1947: __. Print.

18. Garfield, “History – Unification.”

19. Krambles 30.

20. Metropolitan Transit Authority Act, 1945 Ill. Laws 1171, now codified at 70 ILCS 3605/1 et seq.

21. Krambles 7-8.

22. Krambles 9. Garfield, Graham. “Chicago ‘L’.org: Operations – Lines –> Humboldt Park.” Chicago ”L”.org. Web. 16 Oct. 2010.

23. Garfield, “Humboldt Park.”

24. Garfield, Graham. “Chicago ‘L’.org: Operations – Lines –> Lake Branch.” Chicago ”L”.org. Web. 5 June 2011.

25. Williams 204.

26. Ibid.

27. “1st Trains Run In New Subway Saturday Night.” Chicago Tribune [Chicago] 18 Feb. 1951: 21. Print.

28. Garfield, Graham. “Pictures for Forgotten Chicago Feature.” Messages to the author. 23 May 2011 and 12 June 2011. E-mail.

29. Garfield, Graham. “Chicago ‘L’.org: Towers & Junctions – Evergreen Junction.” Chicago ”L”.org. Web. 8 May 2011. Garfield, Graham. “Chicago ‘L’.org: Operations – Lines –> Milwaukee-Dearborn Subway.” Chicago ”L”.org. Web. 8 May 2011.

30. Garfield, Graham. “Pictures for Forgotten Chicago Feature.” Message to the author. 12 June 2011. E-mail.

31. “Plan Group OK’s Razing CTA Station.” Chicago Tribune [Chicago] 27 Feb. 1964: W1. Print.

32. “Five Contracts Awarded at Board Meeting.” CTA Transit News (Sept. 1964): 3. Print.

33. “69 Year-Old Logan ‘L’ Structure Being Scrapped.” CTA Transit News (Dec. 1964): 4. Print.

34. Garfield, Graham. “Chicago ‘L’.org: Towers & Junctions – Washington Junction.” Chicago ”L”.org. Web. 20 May 2011.

35. Garfield, “Washington Junction.” Garfield, Graham. “Chicago ‘L’.org: Operations – Lines –> Cermak Branch.” Chicago ”L”.org. Web. 30 May 2011.

36. Garfield, Graham. “Chicago ‘L’.org: Operations – Lines –> Paulina Connector.” Chicago ”L”.org. Web. 20 May 2011.

37. Garfield, “Cermak Branch.”

38. Garfield, “Humboldt Park.”

39. “CTA to Operate Humboldt Park ‘L’ as Shuttle.” Chicago Daily Tribune [Chicago] 2 Feb. 1951: B9. Print. Garfield, “Humboldt Park.”

40. “CTA’s Trimming of ‘L’ Branches Draws Near End.” Chicago Daily Tribune [Chicago] 21 Apr. 1953: A3. Print. Vandervoort, Bill. “Chicago Bus and Streetcar Routes.” Chicago Transit & Railfan Web Site. Web. 22 May 2011 (noting that North Avenue’s streetcar route was converted to trolleybuses on 3 July 1949).

41. “Humboldt Park ‘L’ Abolished by CTA Order.” Chicago Daily Tribune [Chicago] 16 Apr. 1952: B9. Print.

42. “Suit Demands Humboldt Park ‘L’ Be Restored.” Chicago Daily Tribune [Chicago] 6 May 1952: 4. Print.

43. “Humboldt Park ‘L’ Trains Discontinued Today; Put in Buses.” Chicago Daily Tribune [Chicago] 5 May 1952: 1. Print.

44. “Start Wrecking Last of Humboldt Park ‘L’.” Chicago Daily Tribune [Chicago] 4 Jul. 1961: 13. Print.

45. Garfield, “Humboldt Park.”

46. Garfield, Graham. “Chicago ‘L’.org: Stations – Wells Street Terminal.” Chicago ”L”.org. Web. 29 May 2011.

47. Ibid.

48. Ibid.

49. Ibid.

50. Ibid.

51. Ibid.

52. Garfield, Graham. “Chicago ‘L’.org: Operations – Lines –> Stock Yards.” Chicago ”L”.org. Web. 5 June 2011.

53. Ibid.

54. Garfield, “Lake Branch.”

55. Ibid.

56. Ibid.

57. Garfield, Graham. “Chicago ‘L’.org: Stations – Homan.” Chicago ”L”.org. Web. 6 June 2011.

58. McAlester, Virginia, and Lee McAlester. A Field Guide to American Houses. New York: Alfred H. Knopf, 1984. 262-87. Print.

59. Garfield, “Stations – Homan.”

60. Ibid.

61. Garfield, Graham. “Chicago ‘L’.org: Stations -Conservatory.” Chicago ”L”.org. Web. 6 June 2011.

62. Garfield, Graham. “Chicago ‘L’.org: History – The CTA Takes Over (1947-1970).” Chicago ”L”.org. Web. 29 May 2011.

- B&O’s Original Chicago Entry

- Grove Street

- Old Addresses

- Our Historic Subway Stations

- South Western Avenue Improvement