Born out of an elitist North Shore sensibility, the tumultuous transformation of the Edgewater Golf Club into the egalitarian Warren Park reveals much about the complicated process of real estate development in Chicago. Once the site of society dinners, debutante balls, and gentlemanly privilege, Edgewater Golf Club became a hotly contested space, where a game of “political football” involving various levels of city and state government, community organizations, and private developers, was played out. When the smoke cleared, a case of bribery cost an alderman his job, but North Side residents won ninety acres of hard-fought parkland.

United States Geological Survey

One of the earliest golf courses within city limits, Edgewater Golf Club was established in 1896, sited on a strip of land west of Broadway between Foster and Balmoral. This first course consisted of a mere five holes and when additional land could not be acquired for expansion, the club moved north a year later to a swath of land bounded by Sheridan, Loyola, Albion, and Lakewood.1 Although the club was only located in Edgewater for its first year, the name was retained until dissolution in 1968. The second course was nine holes in length, and expansion was again the issue in 1910 when the club acquired eighty-eight acres farther west at Ridge and Pratt. This tract was purchased from sixteen different owners for a total of $125,500 (over $2.7 million today), and the old property was sold to a developer five days later for $50,000.2

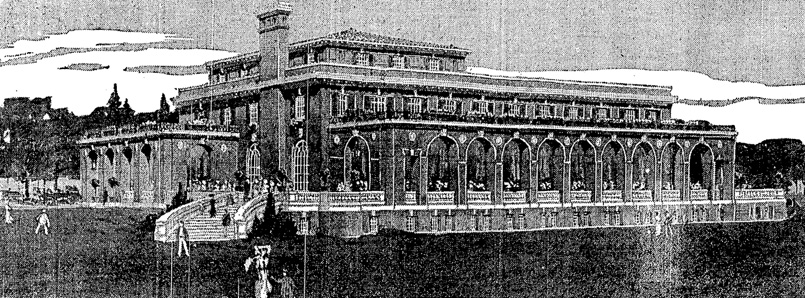

Chicago Tribune

The new course at Ridge and Pratt, designed by prolific landscape architect Thomas Bendelow, opened June 1911. It was a straightforward, economical design with no doglegs, ponds, or other funny stuff, squeezing eighteen holes into the given acreage. Holabird & Roche submitted plans for a palatial Italian Renaissance revival style clubhouse but those plans were not carried through. The firm of Hill & Woltersdorf was employed instead, perhaps to avoid a conflict of interest as Holabird was a member of the club, but more likely because Hill & Woltersdorf charged less. The clubhouse that was built was smaller in scale and laid out in an I-formation consisting of two two-story rectangular segments on each end. Although chintzy in contrast to the Holabird design, the Tudor Revival style employed better reflected the conservative Anglo-American background of much of the club’s membership.

As soon as it opened, Edgewater Golf Club was a magnet for real estate development in West Rogers Park and West Ridge. In 1910, urban-form residential development ceased at Ridge Road, immediately beyond which were primarily greenhouses. The earliest development influenced by the golf course was five houses immediately north of the clubhouse on Pratt Avenue built between 1912-14 by members of the club, including then-president William J. MacDonald. This section of Pratt, located between Seeley and Oakley, developed slowly compared to the surrounding area. Of the nineteen houses eventually constructed along this stretch, ten date to the 1910s, and the remaining nine were built between 1920-49. Until this section of Pratt was widened during the construction of Warren Park in the late 1970s, it was a narrow, private thoroughfare serving this relatively exclusive development. Laurence Warren described it as “only a half street.”3

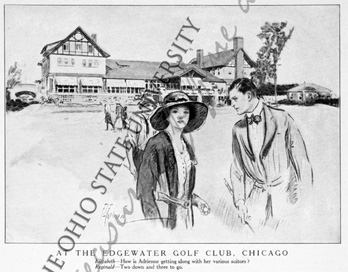

Left: Chicago Tribune. Right: Ohio State University.

The presence of the golf course had an impact on residential development on the North Side beyond a few country club estates. The year the club purchased the new land, McGuire & Orr subdivided the area northwest of the club, perhaps anticipating demand. This subdivision, the Ridge Boulevard addition, led to the construction of the first sewer built west of Ridge Road to drain into the North Shore Channel.4 In 1912, builders Cochran & McGluer were advertising an apartment building located at Broadway and Kenmore as being “fifteen minutes from Edgewater Golf Club.”5 The developer responsible for Edgewater Golf Club itself, William Ludwig Wallen, was active in areas both east and west of the Club, most notably the area around Clark and the street bearing his name.6 Henry Schoolcraft’s 1922 Arthur Avenue Addition, located directly south of the Club bounded by Western, Devon, and Damen, prominently touted close proximity to the club in advertisements. The practice of listing Edgewater Golf Club as an amenity persisted in the marketing of surrounding residential developments into the mid-1960s.

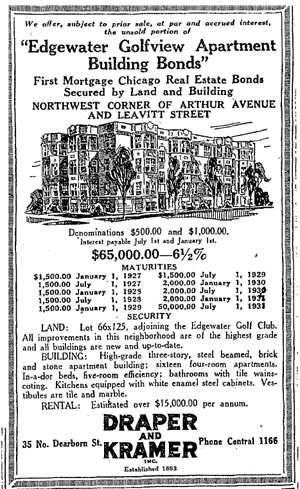

Chicago Tribune Chicago Tribune

A 1925 advertisement for real estate bonds for the Edgewater Golfview Apartments, still extant at the corner of Arthur and Leavitt. Proximity to the golf course is a primary selling point.

|

Edgewater Golf Club had an early history of transience which almost continued into the 1920s. In 1923, the club purchased a 175 acre tract of land in Glenview for around $160,000. Adjusting for inflation, this amounted to around $90,000 in 1910, meaning that the club paid 40% less for twice as much land in Glenview. This time the club was not buying and selling at a loss. Much had changed in the real estate market over thirteen years and by 1923, the value of the Pratt and Ridge tract had escalated to nearly $615,000. While the club could have made a huge profit by moving to Glenview at that time, three months after it was purchased that land was sold to the North Shore Country Club.

Although little of interest apparently happened at Edgewater Golf Club between 1923 and 1953 other than the usual “society notes” twaddle and much ado about Chick Evans, the Glenview affair points to a common issue with urban golf courses. By economic necessity, golf courses are built at the fringes of urban areas where land is cheap and plentiful. In turn, they incite residential demand, driving up property values. The invisible hand exerts pressure on the owners of the course until the price becomes too great to resist. Either the golf club dissolves and fades into memory, or it is rebuilt at the current urban fringe where the process repeats itself. In 1926, then president Judge Dennis E. Sullivan told the Edgewater club members “the club and its property will not be sold…real estate agents are hereby warned to keep off.”7 Ultimately, his advice was not heeded.

Edgewater Golf Club had long been sought after for development when an offer was made in 1953 by an unnamed firm to purchase the land for $900,000. The plan called for high-rise apartments on the site, but the membership rejected the sale.8 Another propostion was made in 1964 by the Sturm-Bickel Corporation which would have involved exchanging the Tam O’Shanter Golf Course in Niles and $800,000 for Edgewater’s land, but this was also rejected.9

The membership finally voted to sell the club to the Kenroy Realtors and developer Jupiter Corporation in 1965 for $7.6 million, giving the developers a November 1, 1967 deadline to come up with the money. There was an immediate backlash from community organizations, first the Nortown Civic Council and later the Allied Northside Community Organization led by Laurence Warren. Community concerns were primarily related to overcrowding and congestion. 50th Ward Alderman Jack Sperling quickly sided with community opposition, introducing a resolution calling for the city to purchase the land for use as a park.10

The developers failed to deliver the purchase price when the deadline rolled around.11 Sperling and 49th Ward Alderman Paul Wigoda introduced a resolution which passed November 1, 1967, downzoning the park from R4 to R2, effectively disrupting the developers’ plan to build high-rises and making the purchase price un-economical for single family housing. However, this action activated a condition in Kenroy’s contract with Edgewater Golf Club, giving them a year extension to come up with the money to purchase the property.12 As a result of the zoning change, Jupiter Corporation pulled out of the deal, leaving Kenroy as the primary buyer.13

Chicago Tribune Chicago Tribune

Rendering of the design for a pedestrian precinct mall in Edgewater Village.

|

The sale was successfully completed a year later in November 1968. Solomon Cordwell Buenz were hired to design the development, producing something very similar to Sandburg Village. Designed to house 8,900 people, the plan for “Edgewater Village” called for 3870 units; 1408 rental, 192 efficencies, 528 two-bedrooms, 2328 condominiums, and 134 townhouses.14 These were to be clustered around “pedestrian precinct malls”, each containing 1000 apartments with underground parking, retail, play areas, and swimming pools.15 Each of the three malls would have one building of twenty stories and five of nine stories. Also included in the plans were a shopping area with parking, a public school, and restaurants. The clubhouse was to have been convereted into a public restaurant and a private health club.16

The Chicago Plan Commission and the Planning and Development Commission both approved the plan initially, and Sperling’s earlier resolution was repealed. The golf course was then rezoned to a planned development site. However, Mayor Richard J. Daley soon began urging the attorney general and Governor Ogilvie to acquire the land.17 Kenroy then filed a suit to compel the Building Commissioner to issue a construction permit.18 The circuit court ruling forced the city to grant a permit; however, in a resolution introduced by Daley, the city council repealed the zoning change allowing for a planned development and the Building Commissioner refused to grant a permit.19

The State of Illinois had begun to take action on the matter earlier in 1969, when the House Conservation and Water Resources Committee passed a bill calling for the purchase of the golf club for use as a state park.20 The bill, allocating $950,000 towards the purchase of the land, passed the House and Senate in June 1969, and Governor Ogilvie signed off three months later. The governor was criticized for the delay by Daley and Lieutenant Governor Paul Simon, and the governor in turn suggested that powerful alderman Thomas Keane “had a piece in the action.”21 The State offered $8 million to Kenroy for the land, but the company raised the asking price to $35 million.22 Negotitations between the state and Kenroy broke down, and the state filed a condemnation suit February 1970. However, a compromise was reached when it became clear the state would likely not be able to afford a price set by a jury.23 The western two-thirds of the property were then sold to the state for $8 million in the summer of 1970, financed through federal grants.24

Chicago Tribune Chicago Tribune

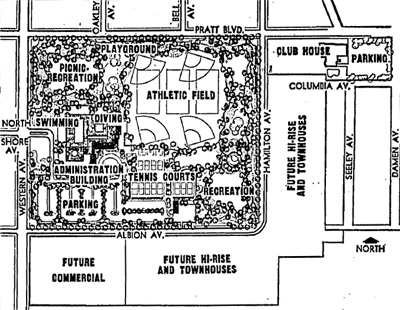

A 1971 proposal for the design of Warren State Park. The sections south and east of the park labeled “future commercial” and “future hi-rise townhouses” were sold to the Chicago Park District in 1974. Albion and Hamilton streets would have been cut through the property. This design was criticized as being cluttered, and the Allied Northside Community Organization lobbied the city to acquire the remaining land.

|

Kenroy retained thirty-two acres, ostensibly with the intention of constructing a high-rise complex. The Allied Northside Community Organization wanted the entire property as open space, and continued to lobby the mayor and park district to purchase the remainder. In 1972, the park district offered $6 million, but just as he did with the state, Kenroy raised his asking price to $12 million.25 After the state turned the park over to the park district, the Chicago Public Building Commission bought the remainder of the property through condemnation proceedings on behalf of the park district in 1974 for $10.3 million.26

When Governor Ogilvie accused Alderman Keane of having “a piece in the action,” he was almost correct, he just suspected the wrong alderman. In April 1974, 49th Ward Alderman Paul Wigoda was indicted for accepting a $50,000 bribe from Kenroy for the rezoning of the Edgewater property from R4 to a planned development site. The rezoning was used at first to activate a clause in Kenroy’s contract with Edgewater Golf Club so that they would have additional time to come up with the total purchase price. Also, the rezoning sought by the developers increased the value of the land, allowing Kenroy to effectively defraud the state and the Public Building Commission.27 The Public Building Commission purchased the land only two months before Wigoda’s indictment. The park district subsequently sued Kenroy for $15 million in damages, but the case dragged on until 1982 and it remains unclear whether or not any money was recovered.

The years of litigation between the final sale of the property in 1968 and the first phase of construction of Warren Park in 1977 saw the property slip into disrepair. The clubhouse remained shuttered and abandoned, dead trees were left untended, and trash and debris was strewn around. The state installed basic fixtures like picnic tables and barbeque stands, but the park was for the most part unstructured.28 In spite of its condition, the park was well used by area residents at the time the park district began construction. Numerous recreational facilities were installed including a nine hole golf course, skating rink, bicycle trail, tennis courts, baseball diamonds, and a toboggan hill.29 In the novel Crossing California, Adam Langer describes the condition of the park in late 1979: “Once an exclusive country club, it was now a vast expanse of overgrown grass, of cracked tennis courts, muddy soccer fields, rusted charcoal grills, and one toboggan hill, a former garbage heap now known to the kids in the neighborhood as Mt. Warren.”30 Warren Park has been greatly improved since that time, and although long in coming, Laurence Warren and the Allied Northside Community Organization showed great foresight in fighting to retain the golf club as open space.

The nineteen houses on Pratt between Seeley and Oakley differ from surrounding residential development in a number of ways. This section of Pratt can be considered a separate subdivision due to larger than normal and irregular lot sizes. The earliest are country club estates, built by club members in the years immediately after the Edgewater Golf Club moved to the Pratt/Ridge location. The most important shared feature, however, is that these are not the tract houses or apartments that comprise much of the surrounding area; rather, they are each unique, built-to-suit single family houses. Together they form a survey of popular residential architectural styles in the Midwest from 1910-1950.

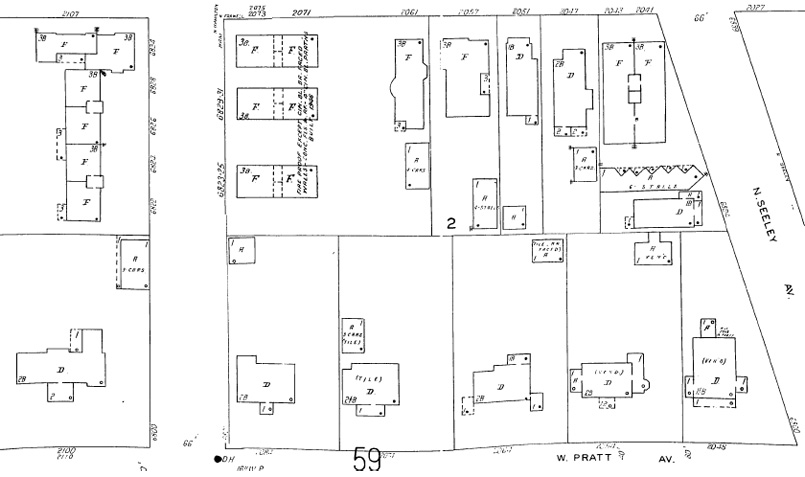

Sanborn

This 1950 Sanborn map shows the eastern most houses of the group, from 2054-2100 Pratt. This is the earliest development influenced by the Edgewater Golf Club. Five of the six houses shown on this map were built between 1912-14, and at least four were financed and occupied by known club members Charles W. Moore, Walter G. Gillette, James R. Cardwell, and then president William J. MacDonald. By 1950, many apartment buildings and three flats had been built in the area, but this was not the case forty years earlier when the area was mostly populated by greenhouses. In fact two greenhouses were in very close proximity to this group; one at the corner of Seeley and Farwell, and one mid-block on Farwell between Hamilton and Bell that remained into the 1950s. To get an idea of the significant size of the lots on Pratt, the closest lot in this image to the standard Chicago lot size is 2051 Farwell, which is still about one-third longer than usual due to the lack of an alley.

2048 Pratt was designed by architect Charles A. Standel in 1914 for Mrs. Seymore Judson Thurber. Not much is known about Standel; he was not an AIA member and the Chicago Historic Resources Survey lists only one of his buildings, a peculiar Tudor-Prairie mish-mosh in the Villa District. Regarding Mrs. Thurber, we weren’t able to find her real name since, during that time, women of her ilk weren’t afforded the luxury of being referred to by name in most newspapers.

2054 Pratt (left) is one of the oldest houses on the block, designed by Architect Robert A. Seyfarth for Charles W. Moore. Seyfarth, who lived in Highland Park, was a residential specialist for Chicagoland’s moderately wealthy, designing Victorian houses in Blue Island, country estates in Lake Geneva, mansions in Beverly and residences in Kenilworth. Seyfarth does not have a consistent style or program, rather he designed the sort of vernacular revival styles found in Ladies’ Home Journal. This one is essentially a standard Colonial Revival with a Classical portico marking the entrance.

For 2064 Pratt, built in 1913 for then Edgewater Golf Club president William J. MacDonald, Seyfarth went for a basic Georgian Colonial design. Charles W. Moore was the contractor, suggesting the obvious point that country clubs often serve as business networking clubs, and building houses is good business. Furthering that point, Charles Seyfarth, most likely the architect’s brother, designed the garage.

Built in 1913, 2074 Pratt is another Seyfarth design built by Moore, this time for club member Walter G. Gillette. Make it look different than the other guy’s, perhaps a side entrance? Stucco the facade and throw some swags over the second story fanlights while you’re at it. Perfect.

Colonial revival houses read like the result of an affront to one’s American-ness, after all, only apple pie and air conditioning are more American. Oddly enough, architect Richard Griesser specialized in industrial plants, especially breweries. That aside, 2084 Pratt, built in 1924 for Stephen Faith, features some top notch woodwork surrounding the entrance. Heavy decoration at the entrance to Colonial Revival houses is appropriated from the Georgian style rather than original Colonial houses proper.31 Interestingly, the entrance is blocked by some ironwork and slightly elevated so that it must be approached from the side. The automobile age had arrived.

Although it can be categorized at first glance as Classical Revival, the portico was not part of Frank D. Chase’s original design and was added later. This is one of a number of expansions and remodels done to this house over the past century. Originally more of a Prairie design, 2100 Pratt was built in 1913 for James R. Cardwell, then president of the Union Draft Gear company. Sited on an enormous 175 x 275 foot lot, this bona fide mansion cost $22,000 in 1913 ($486,024 in 2010), making it the most expensive of the nineteen Pratt houses. The place even had a billiard room with an upper level arcade.

Not to be overshadowed by the pretentious neighboring mansion, Leon Francis Urbain made the most of a $3,500 budget ($53,158 in 2010), creating a streamlined house with Colonial Revival style massing but lacking the superfluity. The only ornament on the house, the ironwork above the door, may well be the most elegant architectural detail on the whole street. 2116 Pratt was built at the tail end of the Great Depression in 1937 for E.R. Hutchins, who lived down the street at 2226 Pratt in an Urbain design built twenty years prior.

Unfortunately, at the time this house was built in 1936, Colonial Revival would remain a popular residential style for another twenty years. The architect was Elmer William Marx, who like Seyfarth designed houses in various revival styles for the moderately wealthy. The name of the owner on the building permit was scrawled illegibly – Doctor something or other.

Side by side, and in contrast to their colonial revival neighbors, 2130 Pratt (left) and 2136 Pratt (right) are two solid examples of indigenous American architectural styles popular in the early 20th Century. 2130 is a Craftsman style house designed by George H. Mansfield in 1921 and the Prairie style 2136 was built for P.C. Passman in 1920, but no architect could be found.

Designed by Louis I. Simon in 1933 for James H. MacFarland, 2142 Pratt (left) is interesting as an example of an asymmetrical Colonial Revival house. Otherwise, it’s paint by numbers architecture. Broken pediment. Check. Round windows. Check. Bay windows. Got it, good. Let’s move on. 2148 Pratt is another asymmetrical Colonial design, but it is much more reductive. Fronting on Bell Avenue, architect H.W. Grugel placed the hearth and chimney in a prominent location next to the entrance, making it the dominant feature. This one was built in 1935 for Dr. John C. Vermeran. Both built in the middle of the Depression, these houses weren’t cheap, costing $15,000 and $14,700 (about $240,000 today) respectively.

These houses were built at the same time, designed by N. Cook for J.B. Jackson in 1919. Little information was available on both parties. Stylistically, they’re an interesting Prairie/Colonial admixture. Balconies, especially on 2208 Pratt (right), with a commanding view of the country club, were probably useful for self-satisfactory gazing.

Elegant Prairie style houses designed by relatively prominent architects, these are the two landmark candidates of the bunch. 2216 (left) was designed by Ralph D. Huszagh in 1914 for Peter L. Fox. For such a seemingly diminutive house, it was fairly expensive at $15,000 ($328,066 today), suggesting that top-quality materials were used. 2226 was built a year later by the aforementioned Leon Francis Urbain for E.R. Hutchins. Nearly twenty years later, Urbain would design 2116 Pratt for Hutchins. Born in 1887 in Indiana, Urbain, also an avid photographer and filmmaker, designed many large apartment buildings in the 1920s. A good example in close proximity to the Pratt houses is the Beachton Court apartment building on the southwest corner of Ashland and Pratt.

2230 Pratt (left) was one of the last designs of Roscoe Harold Zook, best known as one of the architects of the Pickwick Theatre in Park Ridge, who died two months before the building permit application. The newest house of the group, the garage has been incorporated into the house itself, rather than a separate outbuilding. 2236 Pratt is a then-modern update of Colonial Revival vocabulary. Built in 1941 for Dr. H. Meyer, the architect’s name was illegible on the permit.

The group of houses on Pratt is bookended on the west by this two-story Prairie/Craftsman residence designed by Lorenz H. Heinz in 1915 for G.J. Henry. The entire block is characterized by a tension between more modern, indigenous styles and European revival traditions. None of these houses are groundbreaking in any way; each reflects a desire to express individuality while simultaneously fitting in.

1. Al Chase. “Offer to Buy Golf Club for Housing Site.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963), March 20, 1953, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

2. “Real Estate Transaction 5 – No Title.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1872-1922), June 19, 1910, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

Inflation figures obtained using the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Inflation Calculator. http://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm

3. “Edgewater Golf Club Development Still an Undecided Issue.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), May 26, 1968, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

4. “Suburban Gains Market Wonder.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1872-1922), Sep 24, 1911, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

5. “Display Ad 31 — No Title” Chicago Daily Tribune (1872-1922), Sep 8, 1912, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

6. “Other 7 — No Title.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), Jan 16, 1977, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

7. Bernard Judge. “Edgewater Developers Still Remain Confident.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), Feb 15, 1970, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

8. Al Chase. “Offer to Buy Golf Club for Housing Site.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963), March 20, 1953, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

9. James M. Gavin. “Golf Course Swap Offer Under Fire.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), Oct 22, 1964, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

10. “Urges Park at Golf Site.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), Aug 26, 1965, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

11. “Edgewater Golf Club Development Still an Undecided Issue.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), May 26, 1968, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

12. Alvin Nagelberg. “Group Gets Year to Buy Edgewater.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), Nov 2, 1967, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

13. “Kenroy Tells Changes in Edgewater Plans.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), Jul 25, 1968, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

14. Joy Darrow. “Council Meets Today on Edgewater Plan.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), Jan 23, 1969, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

15. “Shopping Center Planned on Golf Course.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), May 18, 1967, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

16. “Edgewater Development Plans Told.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), Jan 16, 1969, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

17. “Daley Seeks Ogilivie’s Aid on Edgewater.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), Dec 6, 1969, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

18. “Builder Sues In Edgewater Golf Club Row.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), Nov 6, 1969, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

19. Bernard Judge. “8 Million State Offer to Buy Golf Club Is ‘Unacceptable’.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), Dec 25, 1969, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 7, 2010).

20. “Edgewater Club Bill Passes Committee” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), May 22, 1969, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

21. “Council Votes Twice on Bill on Edgewater.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), Dec 17, 1969, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

22. Bernard Judge. “State to Move to Buy Edgewater Golf Club.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), Dec 20, 1969, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

23. Pamela Zekman. “Development to Follow Edgewater Compromise.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), Jul 2, 1970, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 7, 2010).

24. “Approve Edgewater Club Sale of 59.3 Acres for State Park.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), Jun 18, 1970, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 7, 2010).

25. “More Golf Club Land Sought.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), Sep 16, 1972, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 7, 2010).

26. Frank Zahour. “City Unit OKs Edgewater Purchase.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), Aug 3, 1974, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

27. United States of America v. Paul T. Wigoda, United States Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit, 521 F.2d 1221, Justia U.S. Court of Appeals Cases and Opinions, http://http://cases.justia.com/us-court-of-appeals/F2/521/1221/70247/ (accessed 7 December 2010).

28. “Walk Thru Warren State Park Turns Into Walk on the Wild Side.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), Oct 3, 1974, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 7, 2010).

29. Michael McCabe. “Warren Park Plan Shows Signs of Life.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), Oct 13, 1977, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed December 7, 2010).

30. Adam Langer, Crossing California (New York: Riverhead, 2004), 5.

31. Virginia McAlester and Lee McAlester, A Field Guide to American Houses (New York: Knopf, 2006), 325.

- Lake Shore Drive Redux

- B&O’s Original Chicago Entry

- Disused Turnarounds

- Tiny Streets

- Chicago’s Shoreline Motels – North