The Chicago Motor Club building was designed and completed within 265 days in 1928 and opened January of the next year. Having been granted National Register status in 1978, the building is widely regarded as one of Chicago’s finest Art Deco style skyscrapers. Between the beginning and ending of the project, the name of the architectural firm of record changed from Holabird & Roche to Holabird & Root, following a reorganization initiated by the death of Martin Roche in 1927.

The day prior to the building’s formal opening, which was January 28, 1929, the Chicago Motor Club building was lauded by an anonymous Chicago Tribune reporter as a “temple of transport” and a “monument to the progress of motordom.”1 Two days later, the Chicago Motor Club placed an advertisement which incorporates a rendering of the building as viewed from below, not quite monumental or temple like, but a sober bastion of modernity, solidity, and responsibility.

Left: Ryerson-Burnham Libraries, Art Institute of Chicago. Middle: Chicago Tribune, 1929. Right: Ryerson-Burnham Libraries, Art Institute of Chicago, 1930.

In another advertisement, the organization self-describes as a “virile and fearless organization of motorists”, appealing to and aligning with the both the romance and burden of auto ownership.2 Sleek curves and speed on one hand, liability insurance on the other. This duality is expressed in the style and design of the building, a Raymond Hood-esque phallus in miniature adorned with machine age flora — a restrained, monochromatic office tower housing a richly textured polychromatic lobby. Yet another 1929 advertisement lavishes even more effusive praise, stating that “prominent architects agree this is the most beautiful building in America.”3 Although this may be a laughable hyperbole, it is difficult to find on record a negative word about the building.

The edifice rises a total of 17 stories — the first is a service floor below the main entrance on Wacker Place. The next two stories contain the lobby, the top floor is a penthouse, while the remaining thirteen are comprised of office space. The organization of the facade is in three segments, horizontally symmetrical with the bottom and top two floors roughly the same height and differentiated from the middle section.

The fenestration is symmetrical as well, with three central window bays in a semi-circular protrusion giving the effect of one large central column, flanked by an additional bay on each side. Despite its symmetricality, the facade gives an undulating impression from street level. Bedford limestone is the primary cladding material, while most of the ornament is executed in metal. There is some relief work in limestone, most notably the peacock designs near the top of the second story and the Chicago Motor Club shield on the cornerstone.

The building is situated on an oddly-shaped small triangular block bounded by Wacker Drive, Wacker Place, and Michigan Avenue. All three are double-deck streets, creating a peculiar topography. The main entrance is actually the second floor and the rear loading area on the first floor opens to MacChesney Court, a short, stone-paved street that is a holdover from the era prior to the improvement and elevation of Wacker and Michigan.

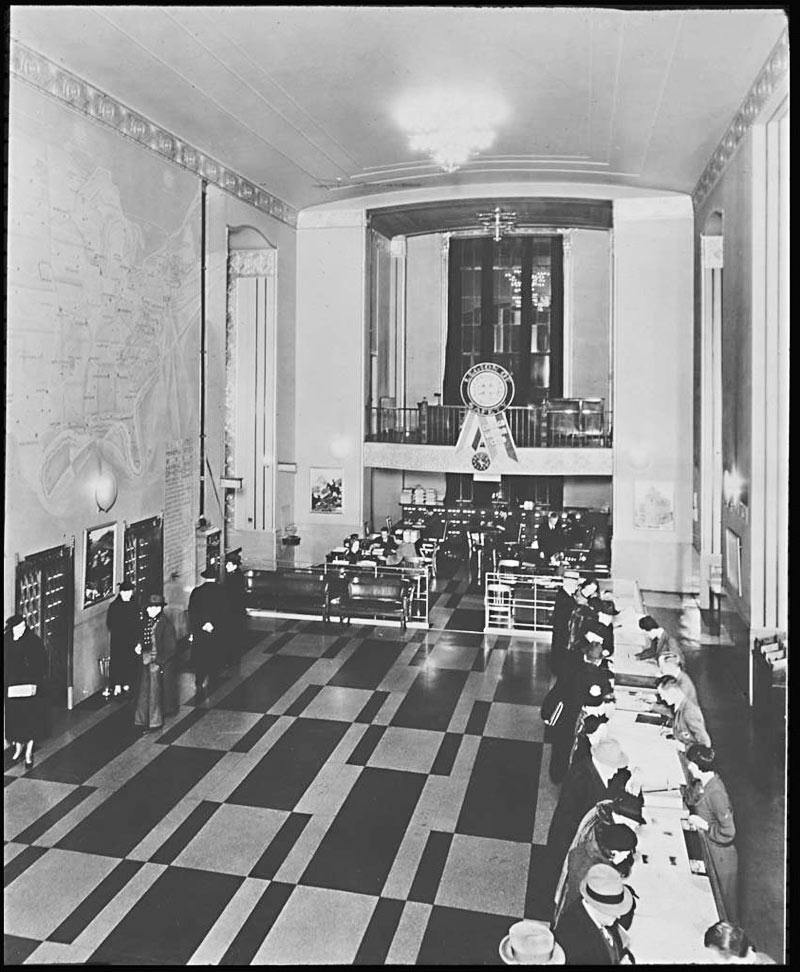

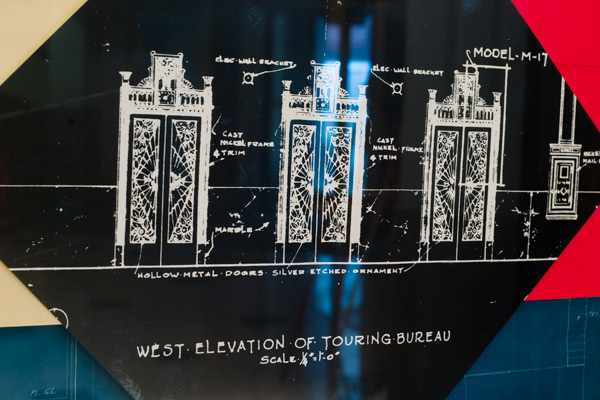

The lobby, which initially housed the touring bureau, is two stories tall, flanked on each narrow end with large windows rising from balconies at the mezzanine level. Both balconies are decorated with the Chicago Motor Club shield front and center, surrounded by geometric and floral motifs which are also employed on the trim, elevators and grilles. The original lighting fixtures were simple circular designs of frosted glass. Some of the chandeliers were removed in a 1982 renovation and placed in storage, however most of these as well as the original sconces remain in place. Another major alteration to the original design involves the floor, which was likely re-done when after the Chicago Motor Club sold the building in 1986. The original floor is a design of contrasting rectilinear forms most likely executed in terrazzo, while the current floor is a rigid diamond tile pattern.

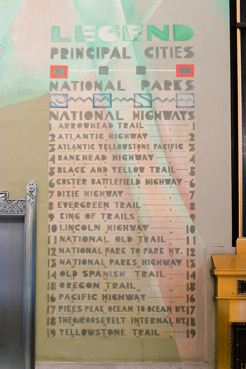

In the lobby, the main attraction is a twenty-nine foot wide mural punctuated by three elevators on the west wall. Designed by the notable muralist John Warner Norton, it depicts an abstracted geometric map of the United States which includes major national highways, parks and cities of that time. Appropriately, the highways included are some of the oldest formalized routes in the country such as the Dixie and Lincoln highways. The mural is highly abstracted and stylized, taking liberties with conventions of mapping representation in interesting ways, including the sawtooth zig-zag lines indicating mountain ranges, and the vibrant seafoam green bodies of water.

The Chicago Motor Club relocated its headquarters to Des Plaines in 1986, citing the need for less costly storage space, a more economical floor plan, and a centralized location to facilitate more efficient dispatch of emergency services.4 The following year, the small elevated section of South Water Street on which the entrance is located was renamed Wacker Place, and the building was in turn renamed Wacker Tower.

The building was operated as rental office space until 1996, when developer Sam Roti purchased it with the intention of converting it into condominiums. The renovation would have cost $10 million in 1996 and would have involved converting each floor into a 4,400 square foot apartment unit with the top floor becoming a duplex penthouse.5 Units may have been priced too steeply, between $1.4 and $4 million, as not enough were sold to warrant going forward with the conversion.6 The building has sat in limbo since then, and at the time of this writing is set to be sold through bankruptcy auction. In all likelihood the building will eventually become a city landmark, as recent reports have indicated that it will receive preliminary landmark status.7

1. “Temple of Transport.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963), January 27, 1929, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed May 1, 2011).

2. “Display Ad 5 — No Title.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963), February 11, 1930, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed May 2, 2011).

3. “Display Ad 25 — No Title.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963), January 29, 1929, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed April 30, 2011).

4. Nels L Pierson. “Voice of the people: The motor club and its move.” Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file), January 19, 1986, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed May 1, 2011).

5. Robert Sharoff. “Turning Old Offices Into New Condo Apartments: In Chicago’s Loop, 2 obsolete buildings are being converted.” New York Times (1923-Current file), May 12, 1996, http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed May 2, 2011).

6. Jill Schachner Chanen. “In Chicago’s Loop, Offices Are Converted to Condos: Sagging commercial market spurs alternative uses.” New York Times (1923-Current file), July 27, 1997. http://www.proquest.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ (accessed May 2, 2011).

7. Lee Bey. “City to pursue landmark status this week for Art Deco former Chicago Motor Club building.” WBEZ: Lee Bey’s Chicago, May 2, 2011.http://www.wbez.org/blog/lee-bey/2011-05-02/city-pursue-landmark-status-week-art-deco-former-chicago-motor-club-building (accessed May 2, 2011).

- Wood Block Alleys

- Harms Park

- Chicago’s Shoreline Motels – North

- St. Ignatius Architecture Graveyard

- South Western Avenue Improvement