Architectural Forum

Bertrand Goldberg in Tower Town is a three-part set of articles, and Postwar Development of Michigan & Pearson is the second in a series of several Forgotten Chicago features highlighting this Chicago-based architect’s one-time residence in the 1930s, and lesser-known built and proposed projects in the Chicago area. This article looks at the demolition in the 1940s of Goldberg’s former 1930s “commune” for retail and housing, and changes to the site since that time.

Holiday

It was reported in November 1946 that New York City-based specialty store Bonwit Teller would build a store on the site of Bertrand Goldberg’s former home at the northwest corner of Michigan and Pearson.1 Facing Chicago’s historic Water Tower, this store would be built on the location of the former Senator Charles Farwell home and stables, and would join existing Bonwit Teller locations in New York City and White Plains, New York, and Palm Beach and Miami, Florida.2

Chicago Tribune

Chicago Tribune

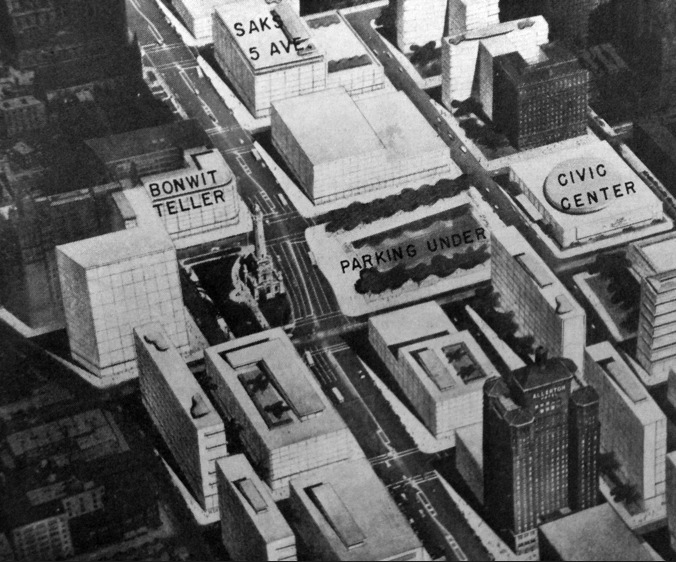

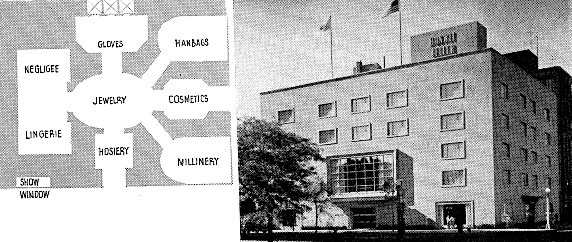

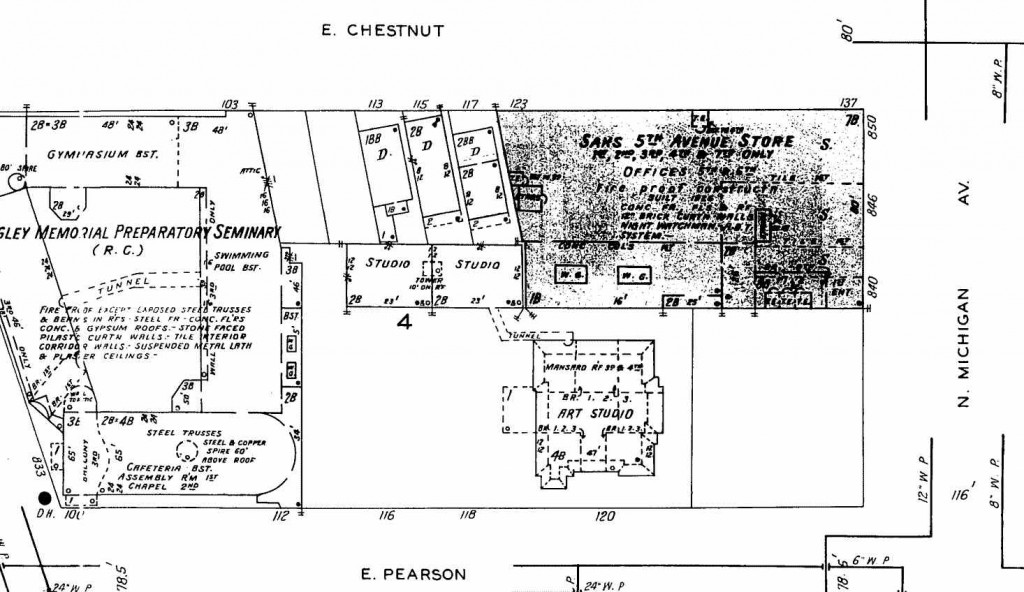

The property was “more than an acre” and was purchased for $575,000 from Webb & Knapp, a New York-based real estate firm.3 Bonwit Teller would build on a lot that was L-shaped, with 306 feet of frontage on Pearson Street, 107 feet on Michigan Avenue, and running behind 840 North Michigan with 133 feet of frontage on Chestnut Street.4 It was announced that the Bonwit Teller building would cover about 15,000 square feet of the lot and that parking would cover the remaining 30,000 square feet of the property.5 The exterior of the building was Indiana limestone, with white marble trim surrounding the windows.6

Architectural Forum

Left: Chicago Tribune. Right: Architectural Forum.

Although the “old Farwell mansion” was torn down to construct Bonwit Teller, It is not clear if the buildings to the rear of the property at 116 and 118 East Pearson (the presumed site of Bertrand Goldberg’s former residence) were demolished at the same time, or had been demolished earlier. Bonwit Teller opened nearly three years after the project was announced, on August 24, 1949, in a building designed Alfred Shaw of Shaw, Naess & Murphy (later Shaw, Metz & Dolio).7

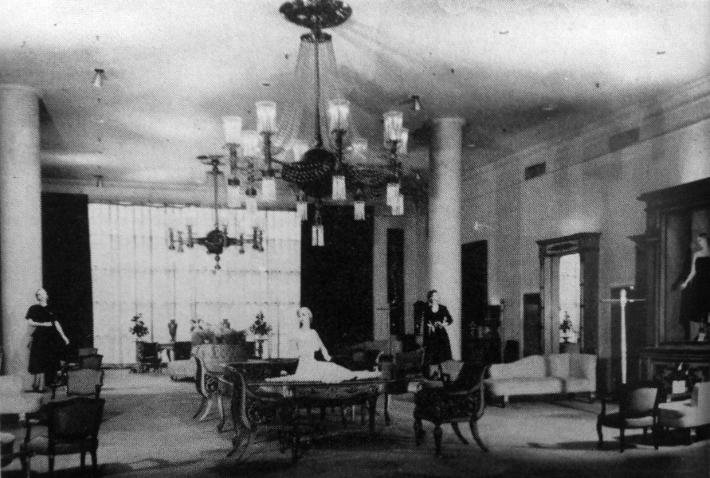

The most noteworthy feature of the new Bonwit Teller store was the second floor dress salon, which had an 18-foot ceiling in a room 100 feet by 50 feet.8 For this room, the Chicago Tribune describes, “an enormous window gives a view of Michigan av., as seen across the water tower square.”9

Realty & Building

Architectural Forum

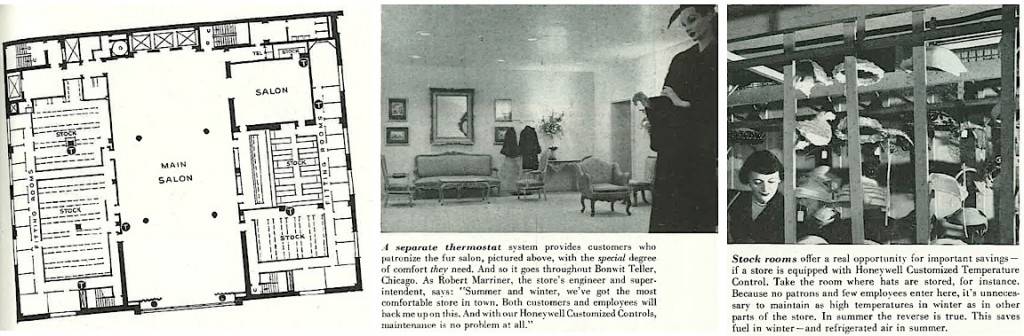

Honeywell Customized Temperature Controls

Left: Chuckman Collection. Right: C. William Brubaker Collection (University of Illinois at Chicago).

In November 1969, Bonwit Teller moved across Michigan Avenue to the recently completed John Hancock Center. In March 1970, the now-empty store at Pearson and Michigan was the site of a farewell party sponsored by local property developer Winston Development.10 Winston Development was expanding and remodeling 830 North Michigan for a new tenant, I. Magnin, as well as constructing the 56-story 111 East Chestnut apartment building next door.11 During the farewell party, it was reported that a “huge yellow wrecking machine” had been stationed at the Pearson Street entrance, “just for effect.”

Following Bonwit Teller’s move across Michigan Avenue, an additional story was added, and the building was expanded from 84,000 square feet to 132,000 square feet, becoming the first Chicago-area location of San Francisco-based I. Magnin.14 The first I. Magnin east of the Rocky Mountains and the 22nd store in chain opened at Michigan and Pearson on October 22, 1971;15 In the Chicago area, Magnin’s would later include locations at Oak Brook Center and Northbrook Court.

Chicago Tribune

Left: The Department Store Museum.

Following the closure of the Michigan Avenue I. Magnin store in June 1992,16 the prominent retail space remained empty for nearly three years, until Borders Books and Music, Filene’s Basement and other tenants occupied it beginning in 1995. The move from high-end specialty store I. Magnin to discounter Filene’s Basement, however, was met with controversy. According to a news account prior to opening, Filene’s Basement had “originally hoped to open the store for the 1992 Christmas season; then it aimed for the 1993 Easter season. But its plans were set back by legal problems over the lease and opposition from merchants in the Greater North Michigan Avenue Association. They objected to a discounter moving into the posh shopping strip”.17

The future tenants of the fourth, fifth and sixth floors of 830 North Michigan are in question again as of this writing. In November 2011, the parent company of Filene’s Basement announced it was filing for bankruptcy protection, and that all stores, including the Magnificent Mile location, would close by 2012. Following the closure of the Borders chain, the fourth primary tenant on the lower floors of the 62-year old building is Topshop / Topman, which opened in September 2011. Additional tenants in 2011 include Columbia Sportswear and Ghirardelli Ice Cream and Chocolate Shop.

The remainder of the former Charles Farewell property, including the site of Goldberg’s former residence, would not be developed for more than 20 years following the completion of the Bonwit Teller store. As detailed in the article “Bertrand Goldberg’s Former Commune”, Goldberg mentioned in his oral history that he lived in the former stables of the Charles Farwell mansion in the 1930s. Concurrent with the remodeling and expansion of the former Bonwit Teller store for new tenant I. Magnin, construction began on the apartment (now condominium) building partially on the site of 116 and 118 East Pearson on June 30, 1970.18 In a newspaper article noting the start of the apartment project (known then as now by its address of 111 East Chestnut), it was reported that the site had previously been used as a parking lot for Bonwit Teller.19 The 56-story apartment building opened in 1972.

Although this area of Chicago has changed tremendously over the past 80 years, buildings on these parcels are built on long-established lot lines. As is common where diagonal streets such as Rush bisect the street grid, the distinct and long-extant lot lines seen in the block bounded by Michigan Avenue and Rush, Chestnut and Pearson Streets are still evident in the shapes of the present-day buildings. Because land and building values are so high on and around North Michigan Avenue, buildings are demolished and replaced with relative infrequency, which may explain why decades-old angled lot lines remain intact. Additionally, replacement buildings in this area tend to be built utilizing the maximum space available on these lots, whether at a right angle or a diagonal.

Sanborn

Sanborn

Left: Google Street View

The final article in this series will detail a Goldberg-designed beauty salon announced in 1937 on the same block, at the southwest corner of Michigan Avenue and Chestnut Street. Presumably unbuilt, Goldberg was mentioned as the architect of what could have been an early high-profile project for the architect, as part of a major renovation of the former Saks Fifth Avenue store into office space and new commercial tenants.

1. “BONWIT TELLER TO BUILD STORE ON MICHIGAN AV.”, Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Nov 30, 1946; ProQuest Historical Newspapers Chicago Tribune (1849 – 1987) pg. 6 (October 6, 2011).

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. AL CHASE. “START WORK THIS WEEK ON TWO STORES”, Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Jan 11, 1948; ProQuest Historical Newspapers Chicago Tribune (1849 – 1987) pg. SW14 (accessed October 6, 2011).

7. “Deluxe Women’s Store Opens”, Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Aug 25, 1949; ProQuest Historical Newspapers Chicago Tribune (1849 – 1987) pg. A7. (accessed October 6, 2011).

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. MARCI GREENWALD. “Fond Farewell to the Old Bonwit’s”, Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file); Mar 25, 1970; ProQuest Historical Newspapers Chicago Tribune (1849 – 1987) pg. B3 (accessed October 10, 2011).

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. “New High Rise”, Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file); Jul 1, 1970; ProQuest Historical Newspapers Chicago Tribune (1849 – 1987) pg. C7. (accessed October 1, 2011).

15. “I. MAGNIN TO OPEN OUTLET HERE IN 1971”, Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file); May 6, 1970; ProQuest Historical Newspapers Chicago Tribune (1849 – 1987) pg. C7 (accessed October 1, 2011).

16. ADAM BRYANT. “R. H. Macy Plans to Close Five I. Magnin Stores”, New York Times, Published: March 06, 1992, http://www.nytimes.com/1992/03/06/business/r-h-macy-plans-to-close-five-i-magnin-stores.html (accessed October 1, 2011).

17. WILLIAM GRUBER. “Michigan Ave. To Get Basement, Others May Not”, Chicago Tribune, October 07, 1994

http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1994-10-07/business/9410070342_1_michigan-avenue-store-magnin-store-store-openings-next-year (accessed October 9, 2011).

18. “New High Rise”, Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file); Jul 1, 1970; ProQuest Historical Newspapers Chicago Tribune (1849 – 1987) pg. C7 (accessed October 10, 2011).

19. Ibid.

- Bertrand Goldberg in Tower Town Part 1: Bertrand Goldberg’s Commune

- Bertrand Goldberg in Tower Town Part 3: Bertrand Goldberg’s Michigan Avenue Project

- Chicago’s Shoreline Motels – Central

- Chicago’s Shoreline Motels – North

- Unexpected Glamour: The Forgotten Work of James F. Eppenstein, Part 2