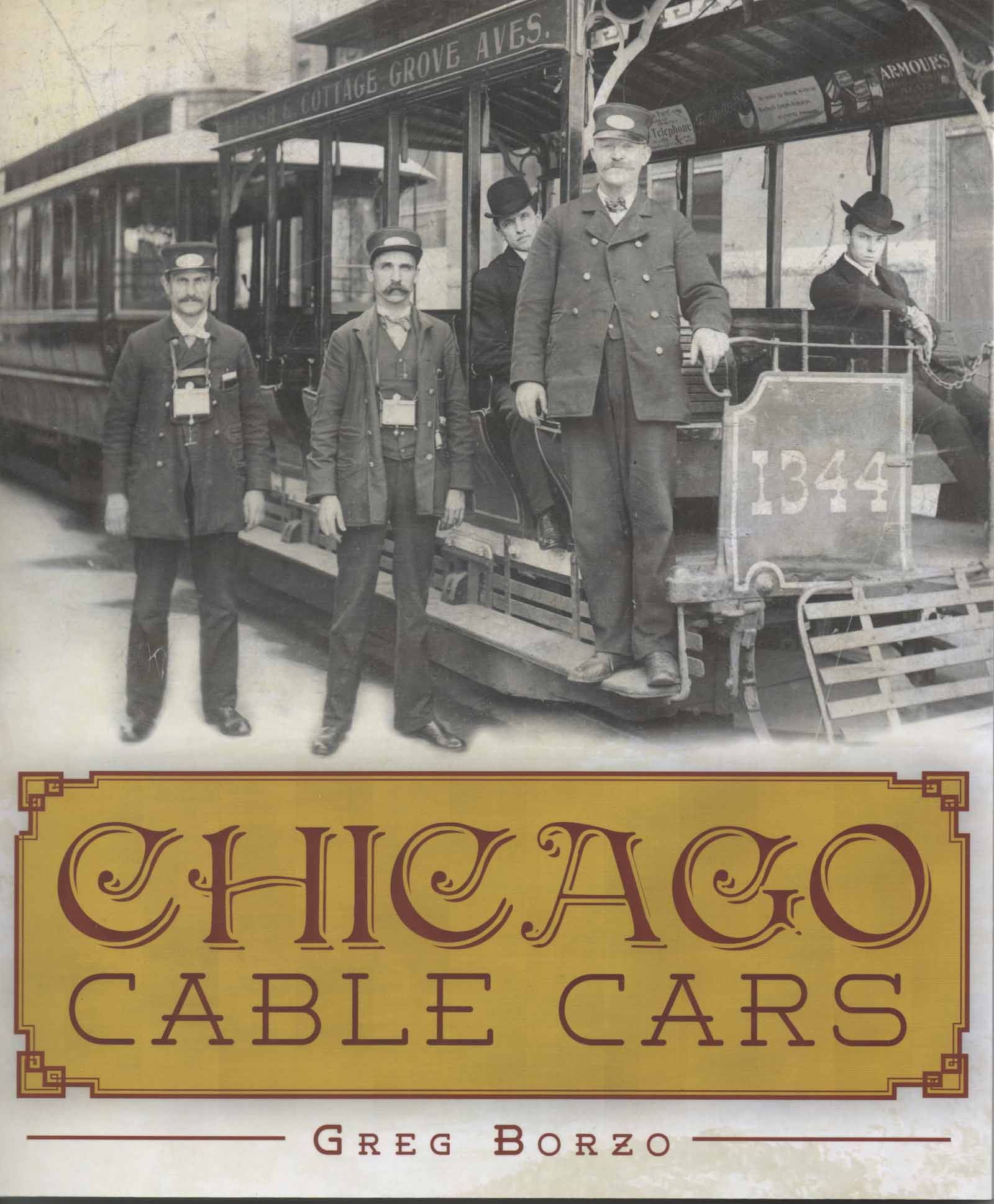

Chicago Cable Cars, a new book, breathes life into the forgotten story of how Chicago came to build the largest cable car system the world has ever seen. During a quarter century, three private cable car companies here carried more than one billion passengers. Published by The History Press in November 2012, the book includes 90 rare, colorful and/or striking images, and includes a forward written by Forgotten Chicago co-founder Jacob Kaplan.

|

In 1882, Chicago took a daring step in transit, as it had done previously in countless other fields including public works, meat processing, interstate transportation, futures trading, water management and building construction. At a time when myriad transit schemes and dreams were being tested around the country, especially locally, Chicago became the first city to try San Francisco’s style of cable cars.

The City by the Bay had started experimenting with cable cars in 1873 and found them an effective albeit expensive solution to carrying modest numbers of passengers up steep hills in a moderate climate. Over the next nine years, entrepreneurs in San Francisco built five relatively short, straight lines totally only 11.2 double-track miles. The rest of the nation did not take much notice of the technology until Chicago decided to see whether cable cars could transport vast numbers of passengers on flat terrain subject to harsh winters.

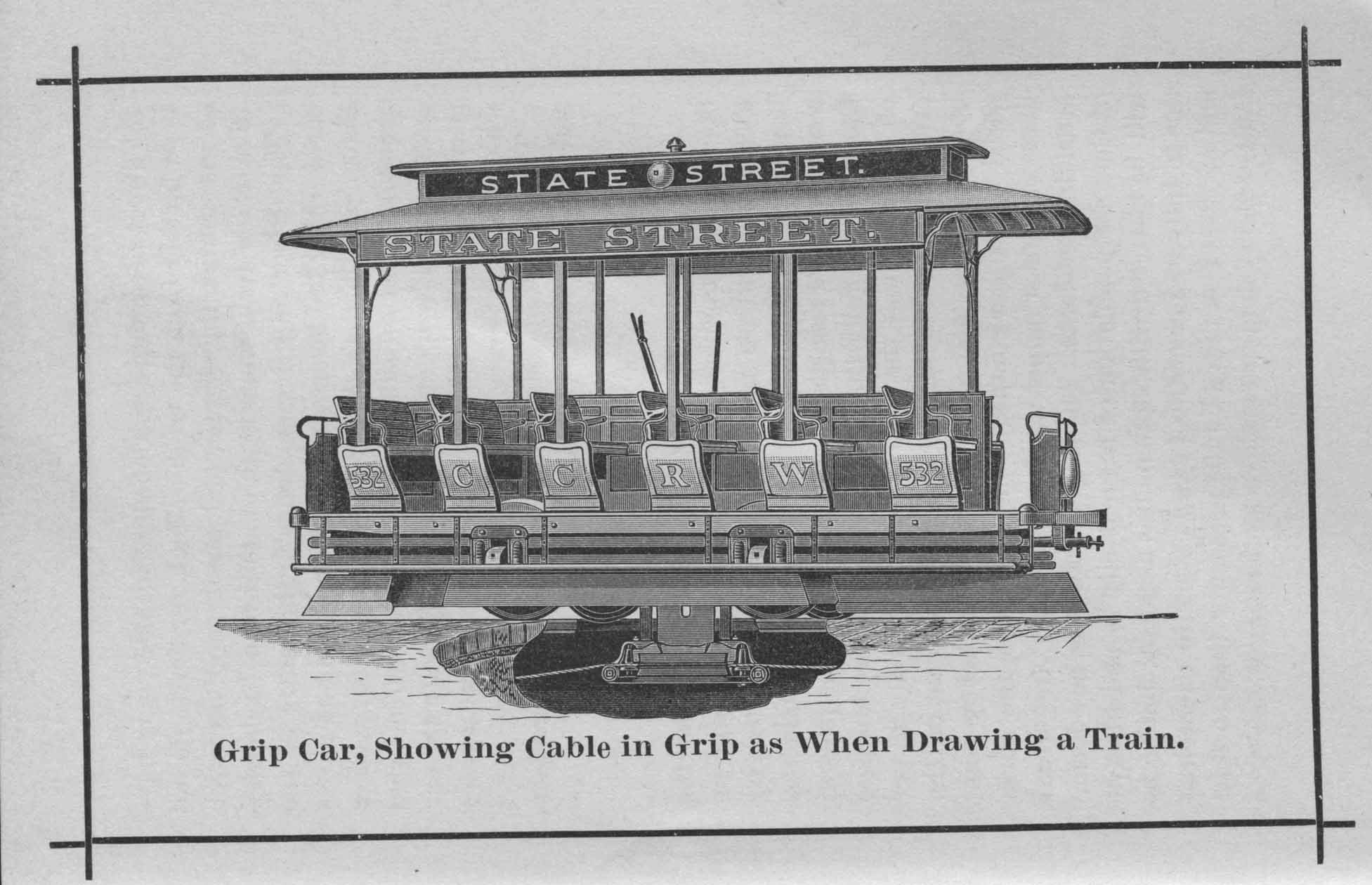

Inaugurated on a cold, blustery day in January 1882, Chicago City Railway (CCR)’s first cable car line ran on State Street from Madison Street to 21st Street. A crowd estimated at anywhere from 50,000 to an improbable 300,000 assembled to witness the propitious event, apprehensive about the risk their city had undertaken. Property owners claimed cable car lines would devalue their investments. Businesses said the fast, dangerous cars would discourage people from visiting their locations. Horse car companies worried the new technology would put them out of work. Horse owners asserted the cable cars would frighten their steeds. Residents feared the quiet, horseless cable cars would maim or kill them.

Nevertheless, the inaugural run went well and the technology appeared to be well suited to Chicago—crowds, cold weather and all. In fact, cable cars were an instant success. Passengers flocked to the first line not only for their transit needs but also for the thrill of traveling at an unprecedented 12 miles per hour. The initial State Street line proved so successful that CCR quickly extended it southward and built a parallel line on Wabash Avenue and Cottage Grove Avenue.

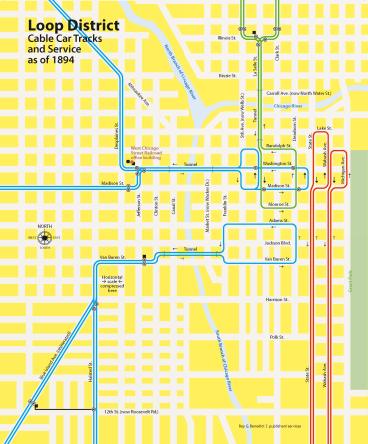

Chicago City Railway also built a large, rectangular “loop” on downtown streets for its cable car trains to turn around. It ran from the corner of State Street and Madison Street east to Wabash Avenue, north to Lake Street, west to State Street and south back to its starting point. Some historians believe that this and subsequent downtown “loops” ultimately lead to the custom of referring to the center of Chicago as “the Loop.”

Soon, other large cities followed Chicago’s example with cable cars, and a nationwide cable car building boom ensued. At the time, cable cars systems were being enthusiastically embraced in many U.S. cities, generating large profits for their builders and operators. Ultimately, 65 transit companies in 29 U.S. cities would build systems.

Roy G. Benedict | Publishers’ Services In 1890 there were three cable car loops downtown. By 1894 that number had doubled. Meanwhile, the number of cable car tunnels under the Chicago River increased from two to three.

|

In just a few years, Chicago would become home of the largest cable car network the world has ever seen in terms of passengers and equipment. After the first two cable car lines on the South Side, Chicago kept building; after gaining control of Chicago’s extensive horse car lines on the North and West Sides, transit titan Charles Tyson Yerkes aggressively converted mile after mile of horse cars to cable cars.

During Chicago’s cable car era (1882 to 1906), three companies provided more than one billion rides using an estimated 3,000 cars. Chicago ended up with the second most miles: 41.2 double-track miles compared with a peak of 52.8 double-track miles in San Francisco. And to operate its systems, Chicago’s cable car companies built 13 powerhouses and countless car barns, office buildings, waiting rooms, repair shops, car building shops and other structures. With a mile of single track costing about $150,000, Chicago’s huge investment in cable car track, infrastructure and equipment added up to $25 million ($600 million in current dollars).

Courtesy of Bruce Moffat This rare, hand-tinted photo shows CCR cable trains passing on Wabash Avenue in front of the Auditorium Building after the building was completed in 1889 but before the Loop “L” was built one block north in 1897. The Cottage Grove train in the center is heading south to 39th Street.

|

Despite Chicago’s huge investment and enormous enthusiasm for cable cars, the technology would soon be obsolete. By the mid-1880s, the electric trolley car eclipsed the cable car, and most cities began scrapping their cable car lines. Due to the huge investment in cable car systems and opposition to overhead electrical wires, however, Chicago clung tenaciously to its increasingly derided cable cars until 1906, nearly a quarter century after opening its inaugural line.

Had entrepreneurs and cities had begun installing cable car lines as early as the 1840s,—when all the essential pieces of the technology were available—the cable car would have had a much longer operating run in Chicago and across the country. On the other hand, if those entrepreneurs had waited just five or six years longer to begin constructing this system, not a single mile of cable car track would ever have been built in Chicago. In other word, if Chicago had not taken the plunge in 1882, cable cars would likely have remained limited to San Francisco.

The comprehensive story of this virtually forgotten, colorful, and significant era in transit history may be read in Chicago Cable Cars (The History Press, 2012). Below is an examination of what happened to the buildings, cars, infrastructure and public works that were associated with Chicago’s vast cable car network.

The remnants of Chicago’s quarter-century cable car story remain plentiful—if you know where to look for them. The vestiges vary from buildings to the absence of buildings, from track structures buried underground to cable cars on display at museums, to a cable car transfer ticket for sale on an online auction site.

Jonathan Michael Johnson’s color photographs—commissioned for the book—show the interiors and exteriors of some of the still-standing structures. These photographs pay homage to Chicago’s cable car era and breathe new life into old bricks and mortar. Owner and founder of Planck Studios, Jonathan is an extremely talented, award-winning photographer.

The most prominent remnants of Chicago’s cable car story are two powerhouses, impressive in their day, but weathered and worn today. These powerhouses, whose “heart throbs are felt miles distant and propel the cables on their endless journeys” (as one engineer colorfully put it) housed the coal- or oil-burning boilers, steam engines and winding machinery that drove the cables.

The North Chicago Street Railroad’s (NCSR) former powerhouse at the northwest corner of LaSalle and Illinois Streets is the crown jewel of Chicago’s cable car remnants. This three-story structure was built at an estimated cost of $35,000 in 1888. “It was a striking presence in the River North area, which was a jumble of low-scale factories, warehouses and shipyards,” says a Commission on Chicago Landmarks Designation Report from 2000.

Jonathan Michael Johnson

This powerhouse drove two cables: one that pulled cable cars through a tunnel under the Chicago River along LaSalle Street and around the downtown and another shorter cable that pulled cars along Illinois Street between Clark Street and Wells Street. Like Chicago’s entire cable car infrastructure, it operated until 1906.

In 1910, a forty-five-by-fifty-foot portion at the building’s rear northwest corner was removed to make room for the construction of an electrical substation for trolleys. The substation remains an electrical facility of the Chicago Transit Authority. The powerhouse’s original smokestack, which was more than seventy-five feet tall, was probably removed at the same time.

More significantly, the building’s façade was moved seventeen feet west of its original location when LaSalle Street was widened in 1929. Although this modification reduced the size of the building, workers faithfully re-created the front exterior so the building is largely intact. “It has good integrity, retaining those exterior physical features most closely associated with its historic appearance and that convey its historic visual character…including important masonry details,” according to the report. The front and south side of the building are faced with finely textured red pressed brick, while the rear and north side of the building are built of common brick.

Over the years, this building has seen many different uses. From the early-1940s through the mid-1960s, Loop Auto Service, an automobile repair shop, occupied the building. In 1967, the old powerhouse was converted to Ireland’s, a popular seafood restaurant. From 1993 to 1999, it housed Michael Jordan’s, a sports bar and restaurant that displayed a huge basketball on the roof of the building. Subsequently, the building housed other tenants, was vacant for several years, and later reopened as LaSalle Power Co., a multilevel entertainment venue. This enterprise closed in 2012, and the building appears to be vacant as of this writing. In 2001, the building was designated a Chicago Landmark, which stipulates that any work to it is reviewed to ensure that its historical and architectural features are preserved.

Much less well-known is the West Chicago Street Railroad’s (WCSR) former powerhouse, still standing in the West Loop at Washington Street and Jefferson Street. Equipment in this building drove two cables: one that pulled cable cars through the tunnel under the Chicago River along Washington Street and around the downtown and another shorter cable that pulled cars from Washington Street and Jefferson Street to Madison Street and DesPlaines Street.

Jonathan Michael Johnson

The building was vacated in 1906, and for decades it housed the Chicago Surface Line’s Legal and Accident Investigation Department. Subsequently, it was modified—more substantially, perhaps unalterably, than the NCSR’s powerhouse on LaSalle Street. Several dormers were added at the roofline, the rear portion of the building was extended, and the smokestack was removed. Most significantly, a large stone wall covers much of the first floor. Today, the building serves as headquarters for Local 134 of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, which also hosts the monthly meeting of the 20th Century Railroad Club.

Other former cable car powerhouse sites are conspicuous by the absence of a contemporary building where they were once located. For example, a CCR powerhouse was once located at the northeast corner of Cottage Grove Avenue and 55th Street, which is currently a large, grassy open space in front of the Friend Family Health Center. In addition, a WCSR powerhouse was located at the northeast corner of Jefferson Street and Van Buren Street where today there is only a parking lot. And a NCSR powerhouse was located on Sheffield Avenue between Wrightwood and Lill Avenues where Jonquil Park sits today.

These former powerhouse sites lack buildings today because the massive underground cable car infrastructure (including foundations, vaults and equipment) that was left behind would need to be removed before a new building could be constructed. In many cases, it is not worth the expense to remove such huge, heavy ruins. For example, the concrete foundation for the machinery in the sixty-by-one-hundred-foot engine room of CCR’s powerhouse on Cottage Grove Avenue was twenty-three feet deep. And when WCSR discovered that its powerhouse at Blue Island Avenue and 12th Street (now Roosevelt Road) was being constructed on quicksand, the foundation had to be extended forty feet underground, which reportedly required the use of one million bricks.

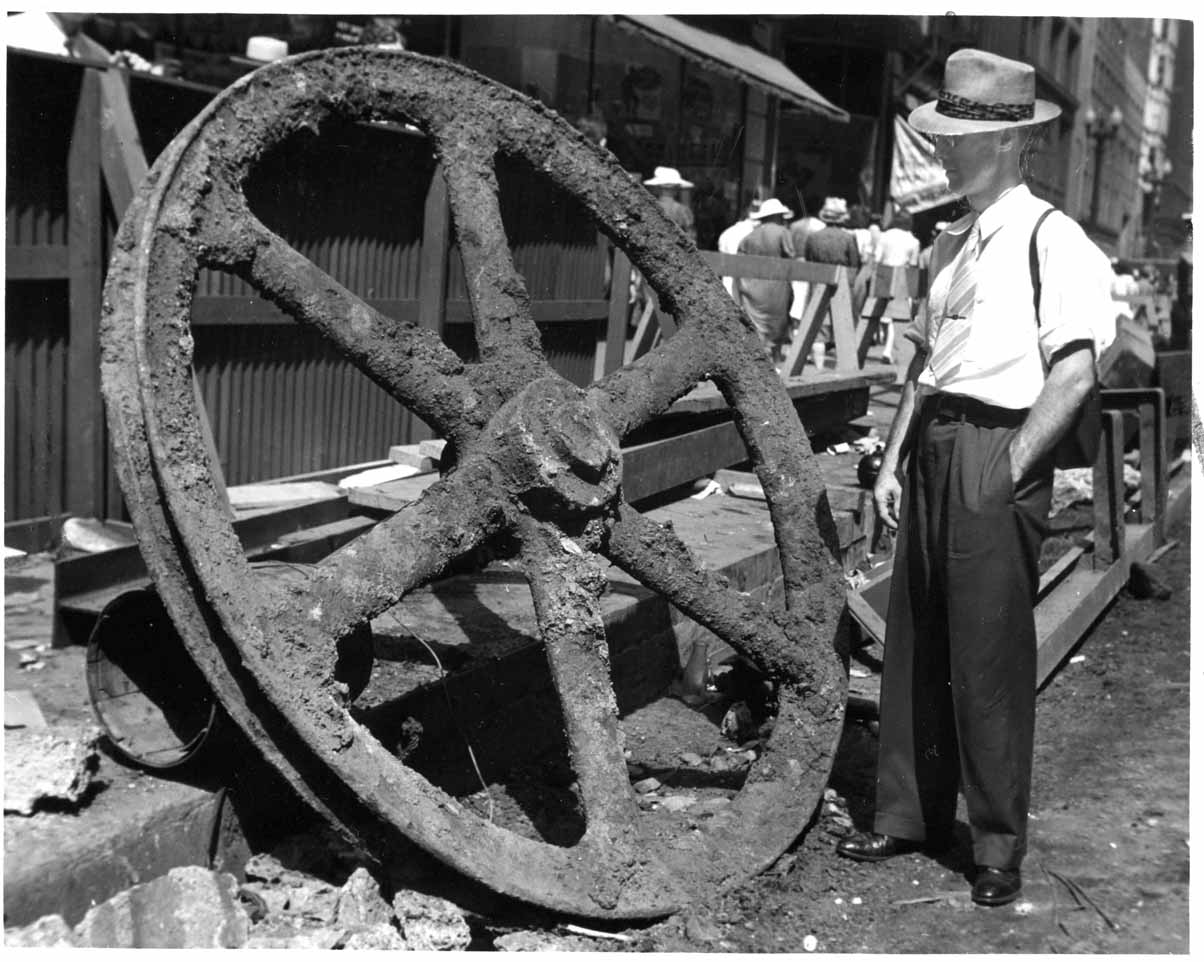

Cable car track and right-of-way infrastructure also lies hidden underneath many Chicago streets. The cables traveled through long, massive conduits built of concrete, brick and iron. These channels twenty to forty inches below ground contained pulley, sheaves, bars and carrier rollers that were held in place by a great number of iron yokes. Spaced approximately five feet apart, each yoke was five feet wide and weighed three hundred to four hundred pounds.

Neither the cable car companies nor the City of Chicago ever made a systematic effort to remove the conduits and accompanying vaults. Instead, the cable car tracks and the tops of the yokes were removed to allow electric trolley tracks to be installed. To this day, street repair projects occasionally unearth remnants of cable car track structure, delaying the work and driving up the cost of the street repairs.

Chicago Transit Authority

Car barns were less massive than powerhouses. A former WCSR cable car storage barn built in 1892 still stands at 2524 S. Blue Island Avenue. Today, Sorini Ring Manufacturing uses it as a factory to make rings for oil drums and storage containers. (Sorini claims to be the longest-running family-owned business in the drum ring industry.) Comparing the current building with old photographs shows that either the second floor of this structure was removed or the façade was shortened.

Jonathan Michael Johnson

Two buildings on Armitage Avenue west of Campbell Avenue were once part of a large complex of as many as eight structures at the end of WCSR’s Milwaukee Avenue cable car line. This complex included cable car and horse car barns, a stable, a blacksmith shop and a carwash, some of which dated back to 1878. Due to fire and demolition, only two of these structures remain. One is a food warehouse, and the other appears to be used for manufacturing and as a studio.

Greg Borzo

A still smaller cable car building remains at 5529 S. Lake Park Avenue along what was once the cable car loop at the end of CCR’s 55th Street cable car line. CCR built it in 1893 in anticipation of the heavy traffic that the World’s Columbian Exposition would generate. This makes it one of the few structures remaining with a tie to the fair.

Greg Borzo

This building’s original purpose remains unknown, but CCR probably built it as a waiting room for trainmen—a place for them to eat, congregate, wait between runs and use the washroom. A portion of the building could have been open to cable car passengers and/or used to sell tickets.

It may be somewhat surprising that this modest building still survives today. As early as 1898, it was converted to a lunchroom, which it remained for decades under different owners. The best-known tenant located there was Steve’s Lunch, which was open from about 1948 to 1966. By 1977, the building was dilapidated and used to store pushcarts for a newspaper delivery service. In 1981, the building was completely, but not necessarily accurately by historic standards, refurbished. Today, it is the home of the Hyde Park Historical Society; as such, it is frequently open for public viewing and/or programs. Information on the Hyde Park Historical Society, along with upcoming events, may be found here.

The underground entrance to Carroll Street in the center of LaSalle Street at Kinzie Street appears to be a cable car vestige—but it is not. There was a cable car tunnel under the river at approximately this location, but that tunnel went much deeper than the current underground passageway, which only serves Carroll Street and the loading docks of buildings along that street. The cable car tunnel surfaced a block north at Michigan (now Hubbard) Street. NCSR cable cars ran through this tunnel to and from downtown. The tunnel was used during the construction of the Milwaukee-Dearborn Subway (now the Blue Line), and filled in 1953.

Alas, there are only two Chicago cable cars in existence today, both built as replicas by Chicago Surface Lines in the early 1930s. Although only replicas, they are accurate and realistic. The original CCR grip car 532 plied State Street, whereas the replica traveled around the city, including in parades and for a stint at a major downtown department store (that name of this store is currently unknown). Since 1938, this car has been on display at the Museum of Science and Industry, where visitors can sit on the car, flip its reversible seats and peer underneath the car to see how its grip once worked. The other replica, CCR 209, is on display at the Illinois Railway Museum in Union, Illinois, about sixty miles west of Chicago. Available for viewing only, this closed trailer seated thirty passengers.

Courtesy of David Clark

San Francisco’s cable cars were designated a National Historic Landmark in 1964. For more than a century after its demise, Chicago’s cable car system was mostly unknown, little-studied, and until now, virtually forgotten.

- Schoenhofen Brewery

- Old Addresses

- B&O’s Original Chicago Entry

- Remnants of the “L”

- Bertrand Goldberg in Tower Town Part 1: Bertrand Goldberg’s Commune