In true Chicago fashion, a plan has been announced and set in stone before anyone has had a chance to comment on it. Michael Reese Hospital’s large multi-building campus has been chosen as the site for the Olympic Village. Originally, it was to be located above the truck yards south of McCormick place, but the city planners jumped on the idea to use Michael Reese when they found out the hospital was closing. The current plan is for the entire hospital complex to be leveled to make way Olympic athlete housing.1

Main Building

Little protest to the project has been heard as of yet. For one thing, few people even know where Michael Reese is, let alone see it regularly. It isn’t located on a major thoroughfare, and it has been isolated in a sea of urban renewal projects, including it’s own, since the 1950s. However, once one does see the Reese campus, it is hard to deny that something worthwhile will be lost if the plans go through.

Hospital architecture can often be uninspired and utilitarian, but most of the buildings at Michael Reese couldn’t be further from this assessment. The main hospital building is the absolute gem of the complex. A Chicago School building designed by the firm of Schmidt, Garden and Martin of Ward’s Warehouse and Schoenhofen Brewery fame, the building exudes the influence of Louis Sullivan as well as Hugh Garden’s own distinct style. The building is truly something unique in the realm of Chicago’s architecture.

After the Hebrew Relief Association’s hospital was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1871, a void was created for a Jewish hospital in the city. Fortuitously, Michael Reese, a wealthy real estate developer who died in 1877, left funds in his will to build a new hospital, which was completed in 1880. It was open to everyone regardless of nationality or race, the request of Reese’s heirs. Many medical innovations took place at Michael Reese during it’s operation, such as the first incubator station for premature babies. It has been known as one of Chicago’s prominent hospitals, with people coming from all over the city and beyond to receive treatment.2

As the demographics of the neighborhood around the hospital had changed by the 1950s, Michael Reese decided to stay and become an agent of urban renewal, instead of deserting the neighborhood. The South Side Planning Board was formed with Michael Reese and other area institutions, notably IIT. The hospital turned to Walter Gropius, the former director of the Bauhaus, for assistance in planning the postwar campus, though he was rarely directly involved.3 Reginald Isaacs from the Harvard Graduate School of Design was brought in to head the hospital planning staff. He was previously involved with the federal Public Housing Program and National Housing Agency during the New Deal, and had also served on the Chicago Planning Commission.

Urban Renewal, 1955

The hospital’s urban renewal projects greatly expanded the hospital at the expense of the surrounding neighborhood. Houses and businesses were torn down en masse to make room for new hospital buildings. The land clearance was actually completed by the Chicago Housing Authority. The hospital then built on the cleared land, which made the project a public-private cooperation. Urban renewal in the area was not just confined to Michael Reese Hospital, however; the urban renewal projects of Mercy Hospital, IIT, South Commons, Lake Meadows, and others were taking place around the same time.

In recent years the hospital was bought by outside investors from Tennessee, and in 1998 it was bought again by a company from Arizona. For-profit hospitals are notoriously difficult to operate in Chicago, and this may be one of the reasons the hospital has been slowly shutting down over the past few years. It is scheduled to close at the end of 2008, and the city has conveniently decided to make it the site for the Olympic Village, should Chicago get the 2016 Olympics.

We hope that more public awareness of the historic nature and architectural heritage of Michael Reese Hospital will lead to the preservation of at least some of the structures on the site. A recently formed organization focused on researching and advocating for preservation of the hospital is The Gropius in Chicago Coalition. They have been bringing new research to light about the influence of Walter Gropius on the Michael Reese campus.

Chicago History In Postcards

Chicago History In Postcards

A postcard of the main building. The bridge to the Meyer House is present, which dates the image to the 1920s or 1930s.

All Our Lives

A 1950s view north towards the older part of the hospital campus. The empty and cleared land will soon become built upon.

All Our Lives

Demolition along Cottage Grove for the Kaplan Pavilion, this one from the Mandel Clinic building roof.

All Our Lives

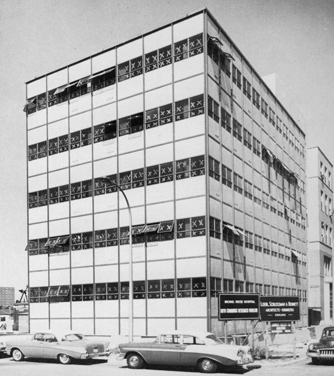

Left: Buildings on Cottage Grove being demolished for the construction of Kaplan Pavilion, designed by Loebl, Schlossman and Bennett. The Sarah Morris Children’s Hospital and Nelson Morris Research Institute are both behind the demolition. They eventually met the same fate.

Right: The Serum Center was located diagonally and down Ellis from the main hospital building. Here, it is being demolished to make way for the Cummings Research foundation building.

All Our Lives

Left: The Cummings Research Pavilion site being readied for construction. The building to the north of the crane is the Florsheim Library which still exists, though it is buried in a set of newer buildings. The Library built in 1935 and was designed by Schmidt, Garden and Erickson.4

Right: The Pavilion under construction. It was designed by Loebl, Schlossman, and Bennett and is still extant, though it has also been somewhat buried in the construction of newer buildings.

All Our Lives |

Then-Mayor Richard J. Daley preparing the cornerstone for the new Cummings Research Pavilion in 1957. |

All Our Lives

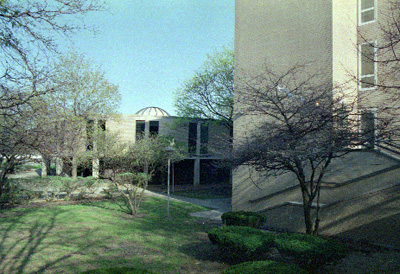

The Psychosomatic and Psychiatric Institute building was one of the first postwar structures built at the Michael Reese campus. This view looks north from 31st Street towards the building, which was designed by Loebl, Schlossman, and Bennett. It is now known as the Singer Pavilion. In a radical concept for psychiatric institutions at the time, it was designed on a small scale, and was meant to promote a cure rather than permanent care. The architects designed the building to avoid looking and feeling like a psychiatric institution, which at the time were typically foreboding structures with barred windows.5 Bennett mentions visiting such places, in an interview:6

They took me out around these places and I said, “My God, you have these great big high ceilings for two people and you got more space up this way than on the floor. Of course everybody will say they’ll catch cold because they’re too close, but that’s silly. You ought to bring that ceiling down to about nine feet, that’s all you need. It will be warmer.” My God they took my advice and in two days they went downtown and got it fixed. Everybody saw it was reasonable. Why the hell did they have to do it that way, because why? They used to have hospices that had ceilings fourteen-feet high and had fifty people in the same damn room. When they brought that into hospital design they still kept the ceiling as high.

All Our Lives

This view to the southwest of the hospital shows the Lake Meadows apartment complex under construction. Like the other numerous urban renewal projects surrounding the hospital, Lake Meadows succeeded in creating an integrated community, but it was at the expense of a dense neighborhood.

All Our Lives

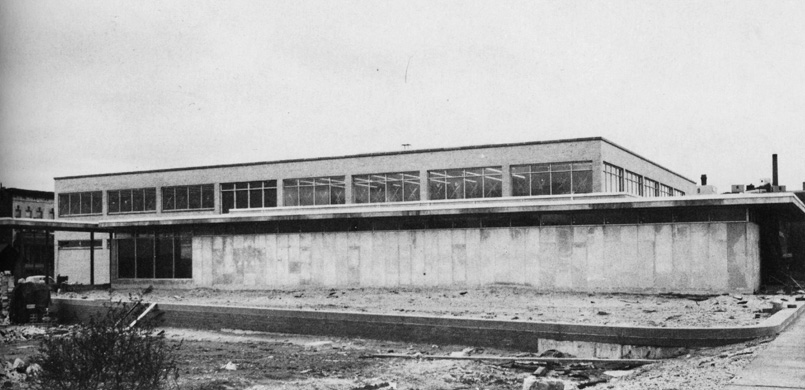

The 3000 block of South Ellis, on the right cleared and awaiting new hospital buildings, and the Research Foundation building under construction on the same site.

All Our Lives

The Research Foundation building under construction in the mid-1950s. Unlike most of the post-war buildings, this building was designed by A. Epstein & Sons, an engineering-architecture firm mainly known for industrial work.7 It has been postulated that the Epstein firm was actually better equipped to design the postwar Michael Reese buildings, but Loebl, Schlossman and Bennett got the job instead because they were German Jews, and there has historically been a rivalry between them and Eastern European Jews, like Epstein. No matter; Epstein worked extensively on the postwar expansion of Mount Sinai Hospital, a large West Side Jewish hospital, and later became its president.8

All Our Lives

The completed building. In recent years this was the Levinson building, and it held a city public health clinic.

All Our Lives

An overall view of the urban renewal zone. The hospital and the Lake Meadows/Prairie Shores complexes combined to totally remake one of the densest areas in the city into one of the greenest ones, with abundant open space.

The main Michael Reese hospital building was designed by Schmidt, Garden and Martin. It is a bona fide Chicago School masterpiece which has been left remarkably intact over the years.

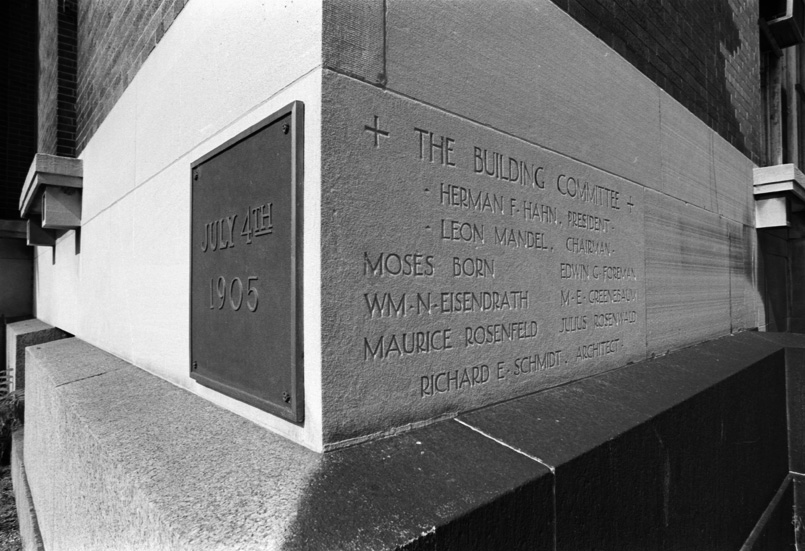

The cornerstone of Main Reese. Though Richard E. Schmidt is credited as the architect, Hugh Garden was the designer. Said R. Vale Faro, who worked for the firm, in an interview:9

“And then besides Garden, of course, there was Richard E. Schmidt, who happened to be the son of a famous German physician in Chicago. His clientele was mainly German Jews; they always admired German doctors very much. They were going to build a hospital, so they invited several architects to enter a competition for this hospital and, of course, Richard E. Schmidt was invited because of his father, and Hugh Garden designed the Michael Reese Hospital. And it was a damn fine piece of design, and Richard E. Schmidt, of course, always sat back. He was a money person in the firm. Thank God he was during the Depression because he kept his partners alive during the Depression with his money, but as an architect he was completely zero. He couldn’t design a large outhouse, really—a small one maybe, but not a large one. Hugh Garden was the designer.”

This Gothic Revival bridge over 29th Street connects Main Reese to the Meyer House, a wing built in the 1920s to house wealthy patients in luxury accommodations.

JK

The east elevation of Meyer House. Residents would have had lake views and breezes.

The Nurses’s residence and school building, and the Mandel Clinic as seen from the roof of Main Reese.

Left: The west elevation of the Rothschild Nurse’s residence. Right: A general view of the campus, facing east from 29th and Vernon.

JK |

A bit of “Gardenesque” ornament from the cornice of the building. Architect Hugh Garden of the Schmidt, Garden and Martin firm was known for his distinctive ornament, as evinced here. |

Left: All Our Lives

Left: Looking north from the roof of the main building, probably in the 1940s. The Keeley brewery adjoined the Michael Reese property to the north. Brewery Avenue, a long gone street, ran through this area, at the north end of which the Conrad Seipp brewery was located.

Right: The same view towards downtown from the main building in 2008. The Keeley brewery was torn down in 1959, and the land was converted to parking, an intern’s residence, and a heating plant for the campus.

Two views on the roof of the building. The house-like structures were at one point once solariums, according to early fire insurance maps.

Left: The newer building in the foreground is the Blum Pavilion, while the taller one in the background is the Dreyfus Research Labs.

Right: Facing east on 29th Street towards the core of Michael Reese.

The parking lot just north of the main building, on which the heating plant is situated. The plant exhibits a Miesian modernist style, similar to the design of his heating plant at IIT a few blocks west.

Two different angles of the Bensinger Public Services building, which is very similar in design to the power plant, down to the red Futura text.

Left: The Baumgarten Pavilion, designed by Loebl, Schlossman and Bennett, and built in 1963.

Right: The wall of the cleverly hidden parking lot behind the Bensinger building.

Left: The Singer Pavilion, another Loebl designed building. It is discussed further on the Historic Images section.

Right: La Cacciata, by Italian sculptor Giovanni Paganin. It was placed on the side of the Singer Pavilion in 1964. Exactly the sort of thing you’d want to see when going to a hospital, right?

The Friend Pavilion, a convalescent care center.

Left: The Siegel Institute for Communicative Disorders building, one of the last buildings added to the campus, opened in 1970.

Right: The round building in this image is the Simon Wexler outpatient psychiatric facility, designed by Ezra Gordon and Jack Levin. It clearly stands out among the other buildings of Reese. Said Gordon in an interview:10

“It was a round building. I often told Roy [head of the psychoanalytic institute], “It’s like your treatment. You know,you go in and you never really come out. You go round and round and round.” He didn’t take too kindly to that. But he was bright and he loved us. We enjoyed him.”

Right: Charles Cushman, Indiana University Archives.

A humble monument marks the spot where the game of softball was invented in 1887. This occured in the gymnasium at the Farragut Boat Club, which stood at 3018 S. Lake Park, on the current hospital grounds. Charles Cushman photographed the Farragut Club in 1949, shortly before it was demolished. It was seemingly used by some sort of veterans club at that time.

Sarah Gordon. All Our Lives. Chicago: Michael Reese Hospital and Medical Center, 1981.

1 Fran Spielman. “Chicago Sun-Times: “Olympic Village could shift west”.” 11/12/07.http://www.suntimes.com/sports/olympics/552690,CST-NWS-oly12.stng (accessed 11/9/08).

2 Wallace Best. “Encyclopedia of Chicago: “Michael Reese Hospital”.” 2005.http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1051.html (accessed 11/9/08).

3 Betty J. Blum. “Chicago Architects Oral History Project: “Oral History of James Ingo Freed”. 2000. http://digital-libraries.saic.edu/cdm4/index_caohp.php?CISOROOT=/caohp (accessed 11/9/08).

4 “Michael Reese Hospital Plans a New Library.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1872-1963),October 27, 1935, http://www.proquest.com.rwlib.neiu.edu:2048/ (accessed November 15, 2008).

5 Betty J. Blum. “Chicago Architects Oral History Project: “Oral History of Norman J. Schlossman”.2005.http://digital-libraries.saic.edu/cdm4/index_caohp.php?CISOROOT=/caohp (accessed 11/9/08).

6 Betty J. Blum. “Chicago Architects Oral History Project: “Oral History of Richard Marsh Bennett”.2001.http://digital-libraries.saic.edu/cdm4/index_caohp.php?CISOROOT=/caohp (accessed 11/9/08).

7 Betty J. Blum. “Chicago Architects Oral History Project: “Oral History of Sidney Epstein”. 2006.http://digital-libraries.saic.edu/cdm4/index_caohp.php?CISOROOT=/caohp (accessed 11/9/08).

8 Betty J. Blum. “Chicago Architects Oral History Project: “Oral History of Arthur Detmers Dubin”. 2003.http://digital-libraries.saic.edu/cdm4/index_caohp.php?CISOROOT=/caohp (accessed 11/9/08).

9 Betty J. Blum. “Chicago Architects Oral History Project: “Oral History of R. Vale Faro”.2005.http://digital-libraries.saic.edu/cdm4/index_caohp.php?CISOROOT=/caohp (accessed 11/9/08).

10 Annemarie van Roessel. “Chicago Architects Oral History Project: “Oral History of Ezra Gordon”. 2004.http://digital-libraries.saic.edu/cdm4/index_caohp.php?CISOROOT=/caohp (accessed 11/9/08).

- Schoenhofen Brewery

- Harms Park

- Fire Insurance Patrol Stations

- South Western Avenue Improvement

- Chicago Motor Club Building